Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

“Place and a mind may interpenetrate till the nature of both is altered,” the trailblazing Scottish mountaineer and poet Nan Shepherd wrote as she drew on her intimate enchantment with the Highlands in her masterpiece The Living Mountain. Having grown up at the foot of Mount Vitosha and spent swaths of my childhood in the Rila mountains of Bulgaria, I too have known the mind-sculpting power of mountains and felt the embers of that knowingness reignited by Journey to Mount Tamalpais (public library).

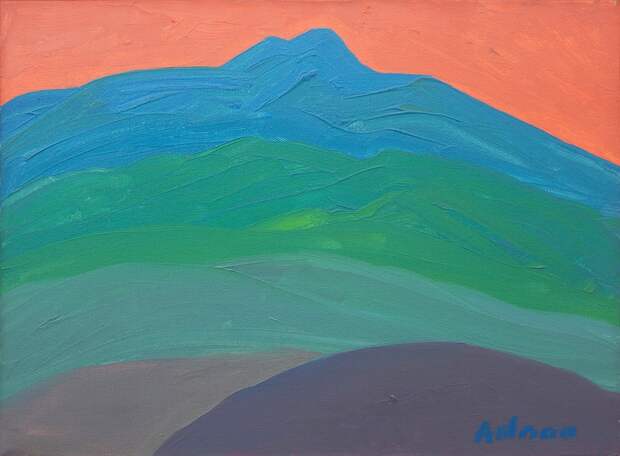

Written shortly after I was born, this uncommonly beautiful book-length essay by the Lebanese-American poet, painter, and philosopher Etel Adnan (b. February 24, 1925), illustrated with 34 of her black-and-white sketches of the mountain, explores the themes that would animate Adnan through her nineties: time, self, impermanence, the nature of the universe, the spiritual dimensions of art, our belonging to and with the rest of the vast interwoven miracle we call nature.

Born in Beirut and trained in Paris — where she would return to spend much of her later life with her partner of more than forty years, the Syrian-born artist and publisher Simone Fattal — Adnan lived and taught in Northern California for more than a quarter century. There, she fell in love with Mount Tamalpais — the first vertebrae of the mountainous backbone of the Americas that stretches all the way to Tierra del Fuego. In its towering presence, she found herself “left with the sort of wonder that the sense of eternity always carries with it,” with a “feeling of latent prophesy.” The mountain became her abiding muse, which she celebrated and serenaded in a flood of paintings and poetic reverberations. Under Adnan’s gaze — generous, penetrating, benedictory — the mountain becomes both metaphor and not-metaphor, both object of reverent curiosity and sovereign subject unbeholden to human interpretation. Hers is a way of looking that embodies Ursula K. Le Guin’s distinction between objectifying and subjectifying the universe. Adnan writes:

Like a chorus, the warm breeze had come all the way from Athens and Baghdad, to the Bay, by the Pacific Route, its longest journey.

It is the energy of these winds that I used, when I came to these shores, obsessed, followed by my home-made furies, errynies, and such potent creatures. And I fell in love with the immense blue eyes of the Pacific: I saw is red algae, its blood-colored cliffs, its pulsating breath. The ocean led me to the mountain.Once I was asked in front of a television camera: “Who is the most important person you ever met?” and I remember answering: “A mountain.” I thus discovered that Tamalpais was at the very center of my being.

Half a century after philosopher Martin Buber considered the tree as a lesson in the difficult art of seeing essence rather than objectifying, Adnan considers the mountain’s essence:

This living with a mountain and with people moving with all their senses open, like many radars, is a journey… melancholy at times: you perceive noise and dirt, poverty, and the loneliness of those who are blind to so may things… but miraculous most of the way. Somehow what I perceived most is Tamalpais. I am “making” the mountain as people make a painting.

[…]

It is an animal risen from the sea. A sea-creature landed, earth-bound, earth-oriented, maddened by its solidity.

The world around has the darkness of battle-ships, leafless trees are spearbearers, armor bearers, swords and pikes, the mountain looks at us with tears coming down its slopes.

O impermanence! What a lovely word and a sad feeling. What a fight with termination, with lives that fall into death like cliffs.

O Sundays which are like vessels in a storm, with nothing before and nothing after!

Out of the actuality of the mountain, Adnan draws an inner reality, rising too like a summit of self-transcendence:

I am at the window and Tamalpais looks back at me. I am in pain and it is not. But we are equals tonight.

[…]

I am amazed, but, more so, I am fulfilled. I am transported outside my ordinary self and into the world as it could be when no one watches.

But more than anything, Adnan finds in the mountain a vital counterpoint to the hubrises of the self. A supreme equalizer of being, it stands as an antipode to our habitual anthropocentrism and self-involvement, humbling us —…

The post Journey to Mount Tamalpais: Lebanese-American Poet, Painter, and Philosopher Etel Adnan on Time, Self, Impermanence, and Transcendence appeared first on FeedBox.