Source: Farnam Street

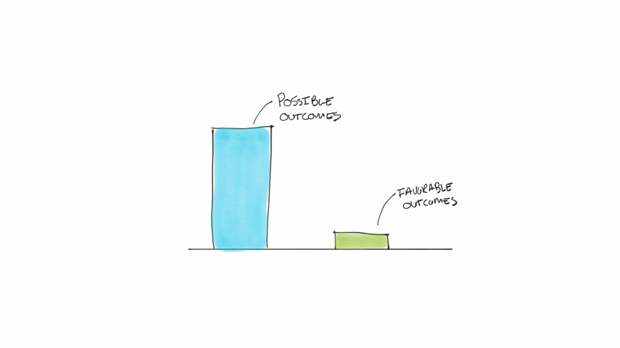

Probabilistic thinking is essentially trying to estimate, using some tools of math and logic, the likelihood of any specific outcome coming to pass. It is one of the best tools we have to improve the accuracy of our decisions. In a world where each moment is determined by an infinitely complex set of factors, probabilistic thinking helps us identify the most likely outcomes.

When we know these our decisions can be more precise and effective.

Are you going to get hit by lightning or not?

Why we need the concept of probabilities at all is worth thinking about. Things either are or are not, right? We either will get hit by lightning today or we won’t. The problem is, we just don’t know until we live out the day, which doesn’t help us at all when we make our decisions in the morning. The future is far from determined and we can better navigate it by understanding the likelihood of events that could impact us.

Our lack of perfect information about the world gives rise to all of probability theory, and its usefulness. We know now that the future is inherently unpredictable because not all variables can be known and even the smallest error imaginable in our data very quickly throws off our predictions. The best we can do is estimate the future by generating realistic, useful probabilities. So how do we do that?

Probability is everywhere, down to the very bones of the world. The probabilistic machinery in our minds—the cut-to-the-quick heuristics made so famous by the psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky—was evolved by the human species in a time before computers, factories, traffic, middle managers, and the stock market. It served us in a time when human life was about survival, and still serves us well in that capacity.

But what about today—a time when, for most of us, survival is not so much the issue? We want to thrive. We want to compete, and win. Mostly, we want to make good decisions in complex social systems that were not part of the world in which our brains evolved their (quite rational) heuristics.

For this, we need to consciously add in in a needed layer of probability awareness. What is it and how can I use it to my advantage?

There are three important aspects of probability that we need to explain so you can integrate them into your thinking to get into the ballpark and improve your chances of catching the ball:

- Bayesian thinking,

- Fat-tailed curves

- Asymmetries

Thomas Bayes and Bayesian thinking: Bayes was an English minister in the first half of the 18th century, whose most famous work, “An Essay Toward Solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances” was brought to the attention of the Royal Society by his friend Richard Price in 1763—two years after his death. The essay, the key to what we now know as Bayes’s Theorem, concerned how we should adjust probabilities when we encounter new data.

The core of Bayesian thinking (or Bayesian updating, as it can be called) is this: given that we have limited but useful information about the world, and are constantly encountering new information, we should probably take into account what we already know when we learn something new. As much of it as possible. Bayesian thinking allows us to use all relevant prior information in making decisions. Statisticians might call it a base rate, taking in outside information about past situations like the one you’re in.

Consider the headline “Violent Stabbings on the Rise.” Without Bayesian thinking, you might become genuinely afraid because your chances of being a victim of assault or murder is higher than it was a few months ago. But a Bayesian approach will have you putting this information into the context of what you already know about violent crime.

You know that violent crime has been declining to its lowest rates in decades. Your city is safer now than it has been since this measurement started. Let’s say your chance of being a victim of a stabbing last year was one in 10,000, or 0.01%. The article states, with accuracy, that violent crime has doubled. It is now two in 10,000, or 0.02%. Is that worth being terribly worried about? The prior information here is key. When we factor it in, we realize that our safety has not really been compromised.

Conversely, if we look at the diabetes statistics in the United States, our application of prior knowledge would lead us to a different conclusion. Here, a Bayesian analysis indicates you should be concerned. In 1958, 0.93% of the population was diagnosed with diabetes. In 2015 it was 7.4%. When you look at the intervening years, the climb in diabetes diagnosis is steady, not a spike. So the prior relevant data, or priors, indicate a trend that is worrisome.

It is important to remember that priors themselves are probability estimates. For each bit of prior knowledge, you are not putting it in a binary structure, saying it is true or not. You’re assigning it a probability of being true. Therefore, you can’t let your priors get in the way of processing new knowledge. In Bayesian terms, this is called the likelihood ratio or the Bayes factor. Any new information you encounter that challenges a prior simply means that the probability of that prior being true may be reduced. Eventually, some priors are replaced completely. This is an ongoing cycle of challenging and validating what you believe you know. When making uncertain decisions, it’s nearly always a mistake not to ask: What are the relevant priors? What might I already know that I can use to better understand the reality of the situation?

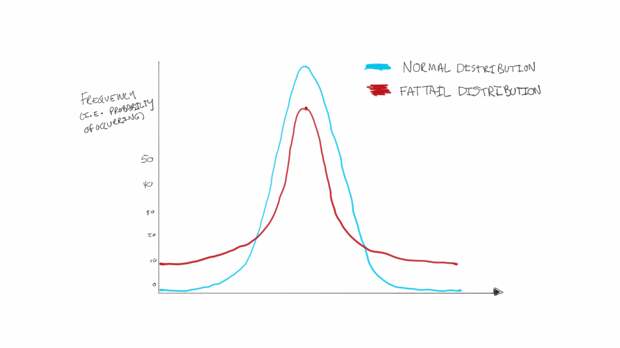

Now we need to look at fat-tailed curves: Many of us are familiar with the bell curve, that nice, symmetrical wave that captures the relative frequency of so many things from height to exam scores. The bell curve is great because it’s easy to understand and easy to use. Its technical name is “normal distribution.” If we know we are in a bell curve situation, we can quickly identify our parameters and plan for the most likely outcomes.

Fat-tailed curves are different. Take a look.

The post Spies, Crime, and Lightning Strikes: The Value of Probabilistic Thinking appeared first on FeedBox.