Author: Matthew Cappucci / Source: Science News for Students

People often use the phrase “eye of the storm.

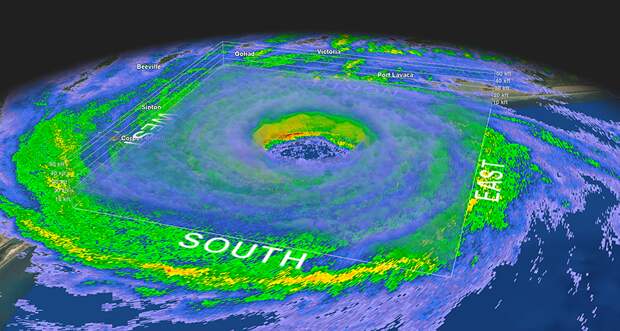

” It’s a term that defines part of a hurricane. It’s that small zone of calm in the midst of chaos, ferocious rains and battering destruction. The wall of winds that swirl around this quiet respite are the polar opposite of this eye. Indeed, they lash out with the cyclone’s greatest fury.That’s saying a lot, because even the outer regions of hurricanes combine Mother Nature’s wildest weather. Their winds can blow ferociously. When their direction is right, these can sweep destructive storm surges inland across coastlines. Their clouds can dump a meter (upwards of 3 feet) of rain — or more — on inland communities. Their unstable winds can even spawn tornadoes by the dozens.

Unstable air — turbulence and rising motion — is key to building and strengthening hurricanes.

The atmosphere naturally cools the farther away you rise from the planet’s surface. That’s why ice crystals may grow outside of windows of a cloud-level airplane — even when it’s a hot summer day at ground level. When the air near the ground is extra warm, it will rise up to pierce through some of the cooler air above. This can create a localized plume of rising air known as an updraft. That’s one surefire sign that the air is unstable.

Warm sea surface temperatures and fairly unstable air are major ingredients in the recipe for a hurricane. Those conditions can serve to fuel quickly rising storm clouds.

Scientists refer to hurricanes are barotropic (Bear-oh-TROH-pik). Such storms form from vertical instabilities. That means there is no real forcing mechanism to move the air sideways. Instead, the air plumes only blossom upwards thanks to extra-chilly air aloft.

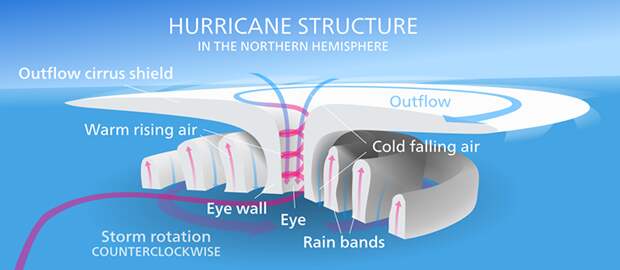

To grow, a hurricane must suck in more air. This air spirals in a counterclockwise fashion toward the center. And as it nears the middle, the air accelerates faster and faster. It speeds up just as an ice skater does when she pulls in her arms and legs.

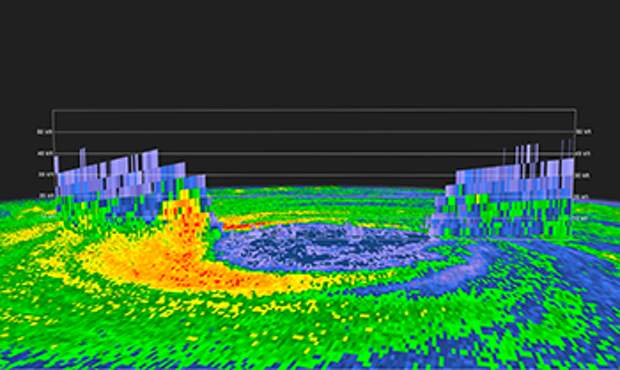

By the time a pocket of air approaches the center, it’s now howling at destructive speeds. This air loses heat to the storm. That energy flows to the cloud-free “eye” of the storm, then exits up and out the top. Inside the eye, the winds disappear. A bit of the air curls back down towards the ground and erodes any moisture, eating away at clouds. Sometimes blue skies appear directly overhead.

Circling just outside the eye are the winds that make up the eyewall. They’re the scariest, nastiest, gnarliest part of the storm. They form an unbroken line of extremely powerful downpours. In strong hurricanes, these winds can roar to 225 kilometers (140 miles) per hour.

Twirling masses of air

Despite how strong these storms are, one thing is often missing: lightning.

With a storm so intense, one would expect its clouds to trigger plenty of lightning. Most don’t. And it all has to do with the motion of the air pockets — known as parcels — spiraling into the eyewall.

Ordinary thunderstorms develop vertically, meaning upright from the ground. It’s a bit like a bubble of air rising from the bottom of a pan of boiling water. In hurricanes, however, there is so much rotational energy that the air doesn’t climb up directly. Instead, it takes a swirly, roundabout path.

Parcels of air swirl slantwise into the storm, inward from all directions. All the while, they rise.

So while they reach the height of typical thunderstorms — 10 to 12 kilometers (6.2 to 7.5 miles) — the rising motion isn’t quite as strong, given that they’re circling like a merry-go-round. In order to spark lightning, there need to be lots of straight-up-and-down rising motion.

That’s why eyewalls only spit out sporadic bolts when a storm is intensifying — when more air…

The post Explainer: The eye(wall) of a hurricane or typhoon appeared first on FeedBox.