Author: Cara Giaimo / Source: Atlas Obscura

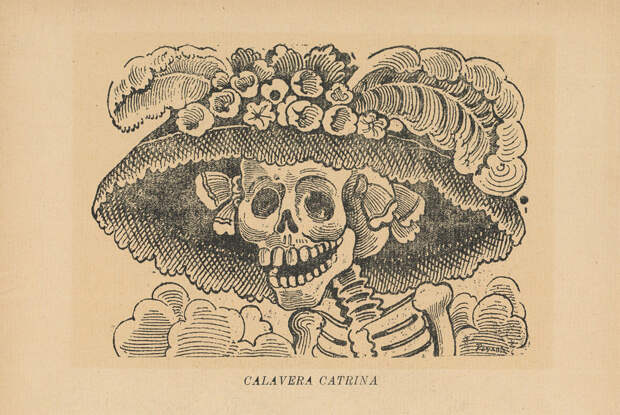

You may recognize the image above. It’s a difficult one to forget: a laughing skeleton in a flowery hat. You might have seen her in Diego Rivera’s iconic mural, Sueño de una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central). There, she links arms with a likeness of her creator, José Guadalupe Posada. Or you might have spotted her in the Disney/Pixar film Coco, taking the hand of the main character in order to guide him into the Land of the Dead.

This skeleton, known as “La Catrina,” is one of Posada’s best-known calaveras: illustrations of skeletons, boldly drawn and thickly inked, and much more energetic and expressive than you’d expect, given their biological state.

Although the figures have become closely associated with the holiday Dia de Muertos (Day of the Dead), Posada originally drew his calaveras as political cartoons, commenting on various issues of the day. (“La Catrina,” for instance, was meant to poke fun at early 20th century Mexican women who imitated European fashions.)Over the century or so since they were first created, though, these calaveras have thrown off the shackles of their initial context. They’ve been repurposed by artists to express ideas and opinions across the political spectrum, as well as by advertisers, animators, and activists. For skeletons, they live a whole lot of different lives.

Although he is the most famous illustrator of them, “Posada did not invent the calavera,” says the cartoonist and activist Rafael Barajas Durán. As Regina Marchi writes in Day of the Dead in the USA, images of skulls and skeletons have long been a part of Mexican culture, particularly in the context of Day of the Dead celebrations. (The decorative sugar skulls and darkly funny poems associated with the holiday are both also called “calaveras,” which is Spanish for “skulls.”)

As Durán explains, the skeleton drawings that now go under that name first began appearing regularly in Mexican publications in the 19th century, particularly in journals like La Orquesta, which was known for its biting political satire. “They celebrate the moment when [the country] opened the civil cemeteries,” Durán says. “Before that, all cemeteries in Mexico were the property of the church.” Marchi also points out a connection to the the Danse Macabre, a European motif in which skeletal figures demonstrate various intense, sometimes comical emotions while dancing to their graves. Other scholars trace them even further back, to Aztec depictions of gods and goddesses of the dead.

Like his creations, Posada himself has a complicated and multi-layered legacy. He was born in 1852 in Aguascalientes, Mexico. Not much is known about his early life, although experts think he was first exposed to design work at his uncle’s ceramics studio and a local drawing school. By the 1880s, when he began working as an illustrator at La Patria Ilustrada—run at the time by Ireneo Paz, Octavio Paz’s grandfather—it wasn’t unusual to see skeletons cavorting across newspaper pages.

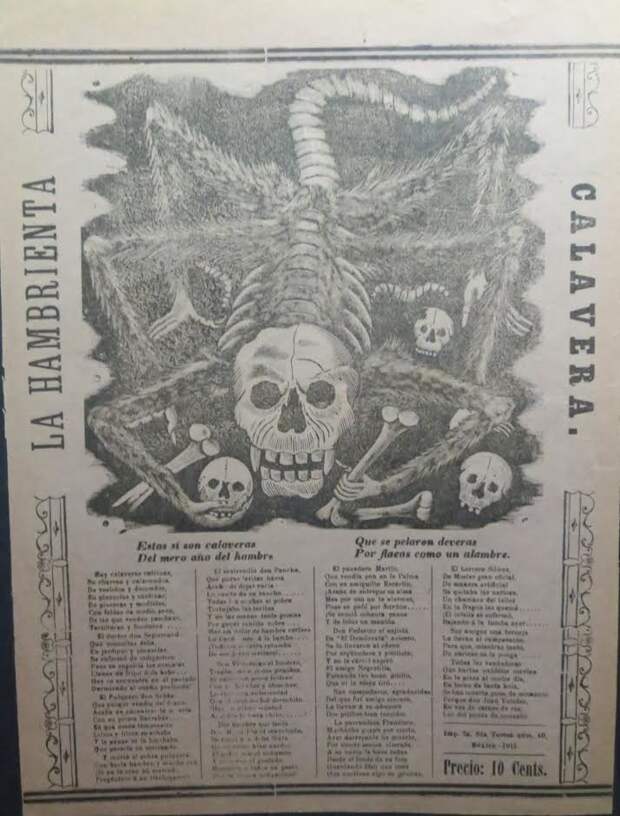

Over the next few decades, Posada worked for a number of publications, making lithographs and woodblock prints. As a hired illustrator, he was prolific by necessity. “There were little publications all around Mexico City at that time,” says Jim Nikas of the Posada Art Foundation. “They would say, ‘Hey, could you make this?’ And he’d have a deadline, and he’d sketch it and make it, and it would go to press.”

Influenced by his fellow artist Manuel Manilla, he developed a distinct style, bold and high-energy, that set him apart. (“His calaveras are wonderful,” says Durán.) He eventually became the head illustrator for Antonio Vanegas Arroyo’s print shop in Mexico City. Often, his illustrations appeared on one-sheet broadsides, accompanied by playful verses that connected them to the issues of the day.

Although Posada’s work spread far and wide, he did not find fame during his lifetime. He died in 1913, “practically alone,” says Durán. “He was not a very well-known artist. He was a popular phenomenon, but he was not acknowledged by … other cartoonists.”

It wasn’t until about a decade later, in the 1920s, that tastemaking artists like Jean Charlot and Diego Rivera began to promote his work. “Since nobody knew about Posada’s life, they made it up,” says Durán. “They made up the idea that he was a revolutionary,” which was likely not true. In a way, they did for Posada what Posada had done for calaveras: they took him, changed him…

The post The Endlessly Adaptable Skeletons of José Guadalupe Posada appeared first on FeedBox.