Author: Natasha Frost / Source: Atlas Obscura

Sometime between the years 1000 and 1600, a group of people set sail from the shores of the South Island of New Zealand, heading east into the great unknown.

For days and days, across a journey of 500 miles of stormy ocean, they did not pass a single speck of land. Finally, on the horizon, someone must have seen some distant islands. Today, they are known as the Chatham Islands, and are part of New Zealand. Then, the travelers named them Rēkohu, or “Misty Sun.”These rocky outcrops on the edge of the world would become their home—a faraway and inhospitable land. On this archipelago of two large islands and a freckling of smaller ones, agriculture was near-impossible. It was chilly, rained 200 days of the year, and had relentless winds so powerful that the island’s gnarled trees grew back on themselves, their branches reaching almost to the ground. East of the islands was a near interminable expanse of ocean, with 5,000 miles separating them from the next landmass: South America.

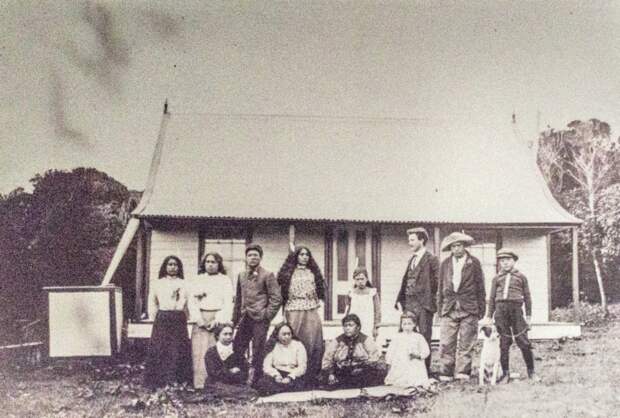

After their arrival, this community of people, who would come to be known as the Moriori, would adapt almost every aspect of their lives to these inhospitable conditions, including their diets, their clothing, their transport, their social structures, and their military practices. For hundreds of years, they lived a pacifist, hunter-gatherer existence—until, in 1835, members of two Māori tribes from mainland New Zealand arrived on the island, killed between a sixth and a fifth of the Moriori, and enslaved the rest.

Exactly how these early settlers came to the Chatham Islands, and what they were looking for, remains a mystery, along with many aspects of how they lived their lives. According to Moriori folklore, quoted by the New Zealand historian James Belich in Making Peoples, “Their atua [god] told them there was land to the east, and they went and peopled it.” The Moriori were descended from the same seafaring people who used double-hulled canoes to discover, and populate, hundreds of islands across thousands of miles of the world’s oceans, from New Zealand to Hawaii to the Easter Islands.

Some of these, like Fiji or Vanuatu, are tropical paradises; others, like New Zealand, are huge land masses—islands so big it would take weeks to walk across them. The Chathams are neither. Chatham Island, the larger of the two main islands, is about 30 miles wide, with about a fifth of its land mass taken up by a central lagoon. Formed by volcanic activity, the islands are fringed by dizzying basalt cliffs, and made up of wildly different topology across a relatively small space. Hill and valleys are thatched with rivers and streams, beneath a green thicket of ferns and nikau palms. Pitt Island, to the south, is around a tenth of the size. The islands, which reach highs of about 65 degrees Fahrenheit in January, are both too cold and too inclement to grow traditional Polynesian vegetables, like sweet potato, taro, or yam. The Chatham Islands have no native land mammals, but a large population of leggy shorebirds and forest fowl, including warbling tui and the melodious bellbird.

To survive, Moriori had to look to the sea. Within a couple of centuries of their arrival, they had developed a functional way of life that remained largely unchanged until the arrival of Europeans in 1791. Instead of developing traditional agriculture, they learned to manipulate the islands’ wild plants, the late historian Michael King wrote in the 1989 book Moriori: A People Rediscovered, “especially kopi—for its berry kernels—and fern root, which they grew in clearings and around the edge of the kopi groves, where the richer soil gave it a pleasantly nutty taste.” Of the hundreds of types of plants on the Chatham Islands, perhaps 30 were edible, King wrote—and none of them especially tasty.

Most of day-to-day existence on the Chathams, therefore, was spent gathering food from the sea that the Moriori needed to survive. In the calmest months of the year, from October through to April, King describes how women and children were tasked with assiduously pulling certain types of shellfish from the rock. Around the same time of year, when the sea was at its least perilous, men used nets woven out of flax to catch cod, grouper, moki, and tarakihi. Year-round, the Moriori hunted seals, which provided them with blubber, meat, and skins, which they used to make waterproof cloaks, with the fur facing inwards. Crayfish, seaweed, and a few coastal and forest fowl rounded off this largely seaborne diet.

There was enough to eat on these remote islands, but life was hard—and often short. Average life expectancy, according to King, maxed out at about 32, with around a third of the population dying in infancy. What killed them was not predators, warfare, or starvation, but damage to their teeth from a lifetime of gritty shellfish. This, in turn, often led to bacterial infections, which were worsened by the respiratory problems common to a damp, cool climate.

The Moriori had come to the islands on double-hulled canoes, but the harsh environs demanded their transformation, too. These were adapted into vessels better suited for fishing in the rough seas around the archipelago. Called korari, or wash-through rafts, they had a floor and sides made of bound reeds, and used inflated kelp to remain afloat amid harsh winds and choppy seas. Some were as much as 50 feet in length, and used to go out to offshore rocks to kill seals or albatross.

But the greatest shifts in lifestyle weren’t in diet or transportation. Being so remote, with a population of just 2,000 people, required an overhaul in the political structure of society, and how disputes were resolved. Moriori coexisted in tribal settlements of up to 100 people, scattered across the two bigger islands. In 1873, the magazine Catholic World published an extended interview with Koche, a Moriori man who had found work with an American vessel. They had…

The post The Sad Story of the Moriori, Who Learned to Live at the Edge of the World appeared first on FeedBox.