Author: Al Williams / Source: Hackaday

A colleague of mine used to say he juggled a lot of balls; steel balls, plastic balls, glass balls, and paper balls. The trick was not to drop the glass balls. How do you know which is which? For example, suppose you were tasked with making sure a nuclear power plant was safe.

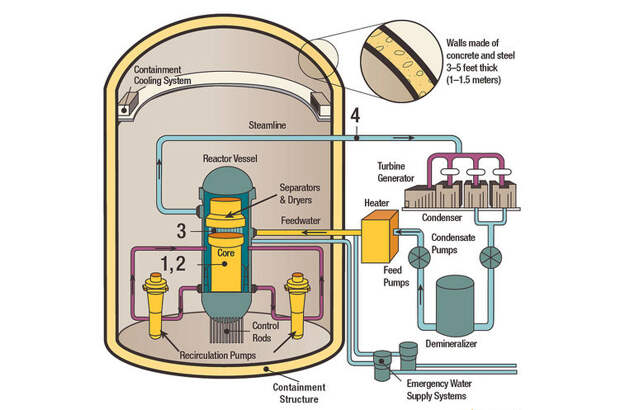

What would be important? A fail-safe way to drop the control rods into the pile, maybe? A thick containment wall? Two loops of cooling so that only the inner loop gets radioactive? I’m not a nuclear engineer, so I don’t know, but ensuring electricians at a nuclear plant aren’t using open flames wouldn’t be high on my list of concerns. You might think that’s really obvious, but it turns out if you look at history that was a glass ball that got dropped.In the 1960s and 70s, there was a lot of optimism in the United States about nuclear power. Browns Ferry — a Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) nuclear plant — broke ground in 1966 on two plants. Unit 1 began operations in 1974, and Unit 2 the following year. By 1975, the two units were producing about 2,200 megawatts of electricity.

That same year, an electrical inspector and an electrician were checking for air leaks in the spreading room — a space where control cables split to go to the two different units from a single control room. To find the air drafts they used a lit candle and would observe the flame as it was sucked in with the draft. In the process, they accidentally started a fire that nearly led to a massive nuclear disaster.

Working with Inflammable Materials

You can build walls 30 inches thick, but you still need to get utilities in and out of the area. This was the case in the spreading room — the area where cables from all over the plant converged on the common control room.

The workers found a 2×4 inch opening near a cable tray. They stuffed the hole with foam and checked it again. There was still a draft and the flame was sucked into the hole, lighting the foam on fire. The inspector tried to knock out the fire, first with a flashlight and then with rags. By this time, the wall was on fire and several fire extinguishers were used to attack the problem but without success. The fire burned on. In fact, the fire extinguishers may have blown burning material out of the hole, making it even worse.

The Failure of the Fire Plan

Because of the efforts to put it out, the fire wasn’t officially reported for 15 minutes. There was also confusion about what phone number to use to report the fire. Perhaps most surprising is that for whatever reason, the operators elected to continue running the reactors despite the fire. According to the official report they then noticed that pumps in the emergency core cooling system were running:

Control board indicating lights were randomly glowing brightly, dimming, and going out; numerous alarms occurring; and smoke coming from beneath panel 9-3, which is the control panel for the emergency core cooling system (ECCS). The operator shut down equipment that he determined was not needed, only to have them restart again.

I wouldn’t operate my car like that, much less a nuclear reactor. After a few restarts, they started talking about shutting things down. Just then, the power output of unit 1 dropped for no apparent reason. They reduced the flow on the operating pumps which then promptly failed. Finally, the operators dropped the control rods to shut down the nuclear reaction.

Doing Everything to Cool the Cores

As you might expect, shutting down a reactor isn’t quick and easy. Electrical supply was lost to several systems in unit 1 including several key instrument and cooling systems. In unit 2, the panels were going crazy and there were many alarms. Then about 10 minutes after the unit 1 reactor started dropping its output, unit 2 followed suit.

Unfortunately, the equipment failed there too and they lost emergency cooling and control of some relief valves. Unit 1 was struggling with very little instrumentation and a reduced number of relief valves. The fear was that if the core did not remain submerged in water, it would melt down.

To keep the core underwater, they used the relief valves to drop the internal pressure from 1020 PSI to under 350 PSI so that a low-pressure pump could force water into the chamber. This decision was met with yet another problem; the low-pressure pumps were not working either so they had…

The post Fail of the Week: A Candle Caused Browns Ferry Nuclear Incident appeared first on FeedBox.