Author: Jessica Leigh Hester / Source: Atlas Obscura

Last year, Megan Heffernan, an English professor at DePaul University, was at the Folger Shakespeare Library and studying a folio of John Donne’s sermons printed in 1640. When she opened it up, she was surprised to find that the inside of the front and back covers were plastered with sheets taken from a book of English psalms.

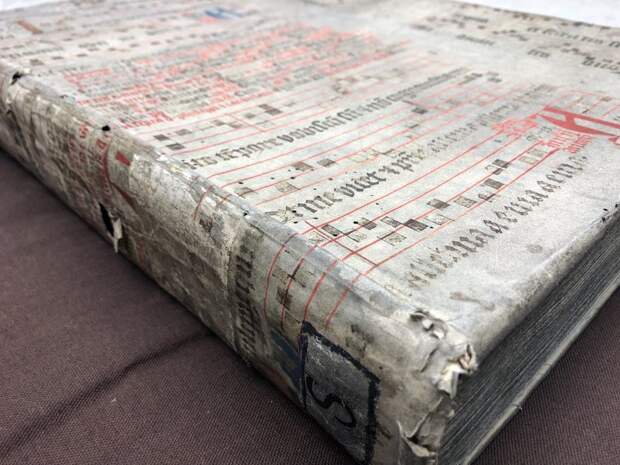

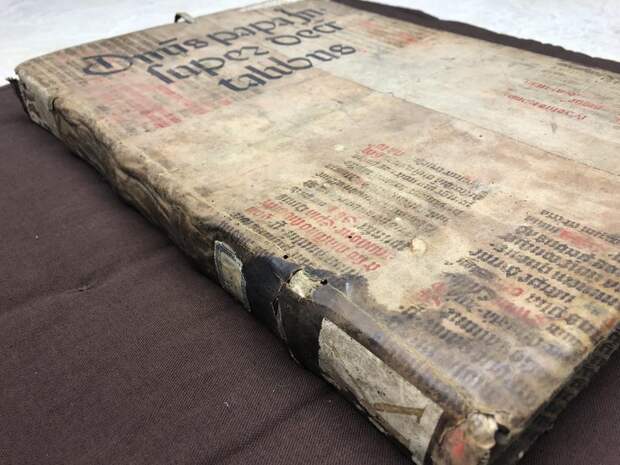

“I just thought, ‘How amazing is it to think about sermons sort of spending eternity rubbing up against a totally different kind of liturgical writing?’” she says. The texts’ creators didn’t intend for them to live together, but when the psalms became “book waste”—essentially, printed garbage—they could end up anywhere.Suzanne Karr Schmidt, a curator of rare books and manuscripts at the Newberry Library in Chicago, jokingly describes these as “turducken books”—a book (or manuscript) within a book within a book. Repurposed scraps like these show up in several dozen places in the library’s collection, either as bindings, mends, or pieces used to reinforce spines.

From the earliest days of bookmaking, binders made use of scraps. Sometimes, it was just mundane material: leases or contracts that had expired or been rendered moot by a scribe’s mistake. In other cases, the bindings illustrate some seismic cultural shift. In these instances, the materials indicate to modern scholars what was important to the people assembling books—or, conversely, what had little or no value to them.

After the Reformation, for example, when Catholicism gave way to Protestantism in Britain, monastic libraries were dissolved and centuries’ worth of manuscripts were suddenly homeless and largely unwanted.

This made them “available to a burgeoning print trade,” Heffernan says, “and they could be torn up into strips, or wrapped whole around books.” The change of faith sapped the Catholic materials’ “value as documents to be read,” she says. But their value as raw material—such as vellum, made from animal skin—remained.

Stumbling across one of these hybrid items now feels kind of magical—as if geography and time have collapsed into your hands. But repurposing scraps in this way wasn’t at all unusual at the time, and Heffernan suspects that it wouldn’t have made much of a difference to readers. “To us, the manuscripts that have been wrapped around books are signs of destruction,” Heffernan says. But to early modern readers, slicing and dicing a text was just a strategy for taking care of other, more coveted objects—like wrapping a textbook in brown paper today. Oversized choir books, which could be twice as tall as a folio, went a long way: “Not quite half a cow,” Schmidt says, “but still a substantial piece of leather.” It was simple practicality. “It’s a moment of typical practice for 16th- and 17th-century bookbinders that seems utterly, delightfully weird to us,” Heffernan says.

Some of this printed waste can end up inside a book’s spine or some other hidden spot, but the rest of the material is not especially hard to spot. It can be unsubtle, pasted in haphazardly or upside down in a newer volume. “The hard part,” Heffernan says, “is figuring out where it comes from.”

To solve that puzzle, scholars run any legible writing through databases such as Fragmentarium or Early English…

The post The Surprising Practice of Binding Old Books With Scraps of Even Older Books appeared first on FeedBox.