Author: Dan Maloney / Source: Hackaday

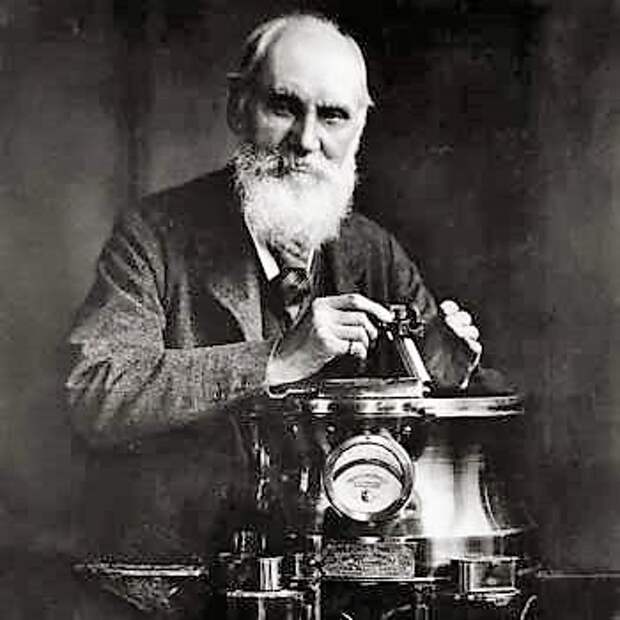

Like many Victorian gentlemen of means, Richard Carrington did not need to sully himself with labor; instead, he turned his energies to the study of natural philosophy. It was the field of astronomy to which Carrington would apply himself, but unlike other gentlemen of similar inclination, he began his studies not as the sun set, but as it rose.

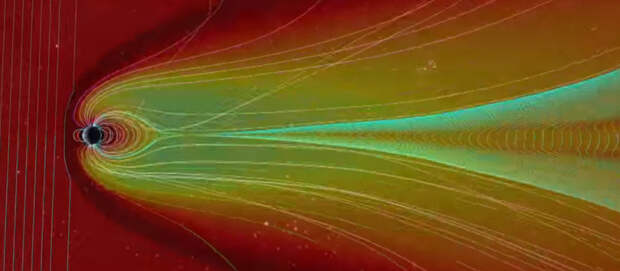

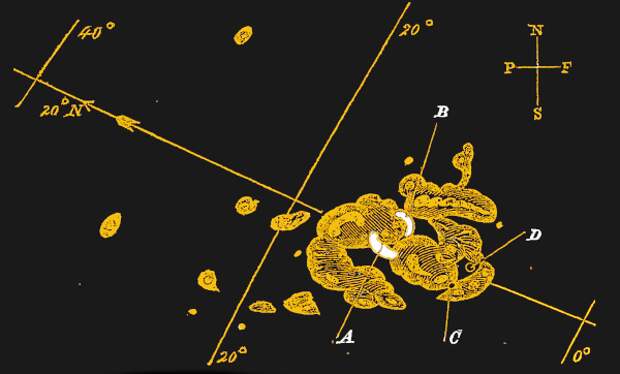

Our star held great interest for Carrington, and what he saw on its face the morning of September 1, 1859, would astonish him. On that morning, as he sketched an unusual cluster of sunspots, the area erupted in a bright flash as an unfathomable amount of energy stored in the twisted ropes of the Sun’s magnetic field was released, propelling billions of tons of star-stuff on a collision course with Earth.Carrington had witnessed a solar flare, and the consequent coronal mass ejection that would hit Earth just 17 hours later would result in a geomagnetic storm of such strength that it would be worldwide news the next day, and would bear his name into the future. The Carrington Event of 1859 was a glimpse of what our star is capable of under the right circumstances, the implications of which are sobering indeed given the web of delicate connections we’ve woven around and above the planet.

A Mortifying Spectacle

Solar science was in its infancy in 1859, and while Carrington’s instruments were crude by today’s standards — a 4-1/2″ equatorial mount telescope projecting an image onto a white card — it was enough. Using similar equipment, astronomers had begun to tease out the secrets of the Sun, observing that the number of sunspots and their location on the Sun’s face occur in cycles.

They also knew that sunspots were associated with observable phenomena on Earth, such as the aurora borealis and aurora australis, and that there was a clear association between solar activity and the Earth’s magnetic field. Some solar observatories even had magnetometers that could record changes on Earth and correlate them to solar activity.The event that Carrington was lucky enough to have watched unfold on September 1 was only one of many outbursts that the Sun would have over a multi-day period. Solar observers reported large numbers of sunspots starting on August 28, with strong aurora being seen at unusually low latitudes starting that night. That suggests that one or more of the sunspots had created a solar flare and coronal mass ejection (CME) of sufficient energy to fling a cloud of plasma toward Earth sometime in the prior two days — while the electromagnetic effects of a solar flare are visible about 8 minutes after it happens, the matter subsequently ejected takes several days to push through the 93 million miles (150 million km) of space between the Sun and the Earth.

The post The 1859 Carrington Event appeared first on FeedBox.