Author: Bethany Brookshire / Source: Science News for Students

Louis Fortier had a problem. The seals would not leave.

Fortier is a marine biologist at Laval University in Quebec, Canada. It was the winter of 2007 to 2008 in the high Arctic and he was aboard a research ship — the CCGS Amundsen. Fortier was there trying to study what fish do under the Arctic ice during the long, dark winter.

As winter closed in, the sun disappeared. The sea began to freeze. The ship eventually sat locked in ice up to two meters (6.

5 feet) thick. The scientists were all alone.Except for the ring seals.

The Amundsen has a moon pool — a hole in the middle of the ship that opens into the water. The air temperature outside might be –40° Celsius (–40° Fahrenheit), but inside the ship, the moon hole is at room temperature, and the water is –2 °C (28 °F). In the high Arctic winter, that’s positively balmy.

Scientists use the moon pool as a convenient way to take measurements without having to cut through thick sea ice. To the ring seals, though, it was a sauna. “They turned it into a social club,” Fortier recalls. “There were up to nine or 10 ring seals at a time in the moon pool. They would sleep there, just floating and spending the day. They liked it. It was warm. They were protected from polar bears.”

Unfortunately, the seals made terrible lab assistants. They hogged the moon pool. They flitted past the researchers’ sensors. Worst of all, they feasted on the polar cod that Fortier was there to study.

Ring seals may be the most annoying (and adorable) of the Arctic’s winter inhabitants, but they’re hardly the only ones. To learn what happens during the bleak season, researchers have had to adapt to the darkness, much as have the creatures that live there. Scientists are learning that even while the Arctic is frozen and dark, it is far from quiet. But with people now moving into the Arctic and lighting up the night, they may cause changes that scientists never dreamed of.

Black sea

A winter night in the high Arctic is no joke. As fall turns to winter in the far north, the sun sets. It will not rise again until spring.

Day and night are the result of the Earth spinning on its axis — the line that runs through the north and south poles. People experience day when their side of the planet faces the sun, and night when it faces away.

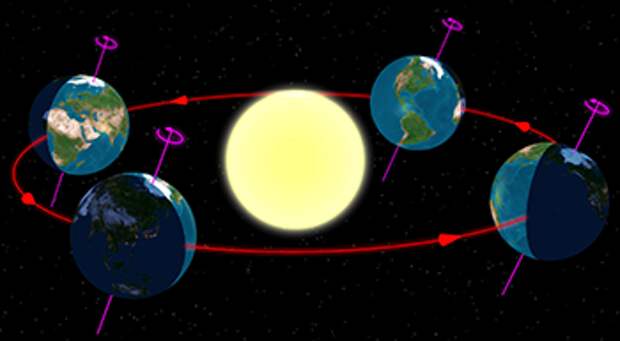

Earth rotates around its axis — a pink line that runs from the North Celestial Pole through the South Celestial Pole. But that axis is tilted, relative to the plane on which the Earth orbits the sun. Because the tilt remains the same all year, this means the North Pole will at times be pointed away from the sun, and at other times pointed toward it. This axial tilt and our planet’s rotation around the sun give rise to Earth’s seasons.

The axis around which Earth spins is tilted in relation to the plane on which our planet travels around the sun. This gives rise to our seasons. This tilt never changes. Instead, as the Earth takes its yearly trip around the sun, the North Pole will point slightly away from the sun during the winter, and toward the sun in summer. When the North pole is tilted away from the sun, days in the Northern Hemisphere get shorter and colder. That’s winter. Half a year later, that tilt will point toward the sun again. Now, the Northern Hemisphere experiences longer, warmer days — summer.

The distance north or south of the equator is described in degrees. The equator is at zero and the North Pole at 90°.The Arctic Circle is 66° north. North of that line, the sun doesn’t even peek above the horizon for at least part of the winter. This is the polar night.

Dawn won’t break again until the tip of Earth’s tilt again starts coming around toward the sun. The further north you go, the longer this takes. At 67° north, Kiruna, Sweden is just above the Arctic Circle. Its polar night lasts 28 days. In Svalbard, Norway, at 78° north, the night spans 84 straight days. At the North Pole itself, the sun doesn’t rise above the horizon for 179 days. That’s nearly six months!

Scientists used to think that this months-long night was silent, dark and basically dead, notes Jørgen Berge. This marine biologist works at the University of Tromsø in Norway. There, he studies life in the ocean.

“We have an expression in Norwegian,” Berge says: When fishermen can’t catch any fish, it’s because there’s a “black sea” or “dark sea.” The term “refers to a dark place where there is no biological activity,” he explains. “It’s a good description of how we used to think of the polar night.”

But not anymore.

Tiny lives in the night

Light feeds life. Without sunlight, plants can’t perform photosynthesis — producing energy from sunlight and water. The plants’ primary production forms the base of most ecosystems. Plants grow and provide food for animals, which provide food for other animals. And so on. To scientists, then, darkness seems like a deal killer.

“The period with light is the time when most of the primary production is happening,” says Anna Båtnes. She’s a marine biologist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. “Plant growth, algae, the whole system is based on this production.” So scientists assumed that without daylight, life slowed and nearly stopped.

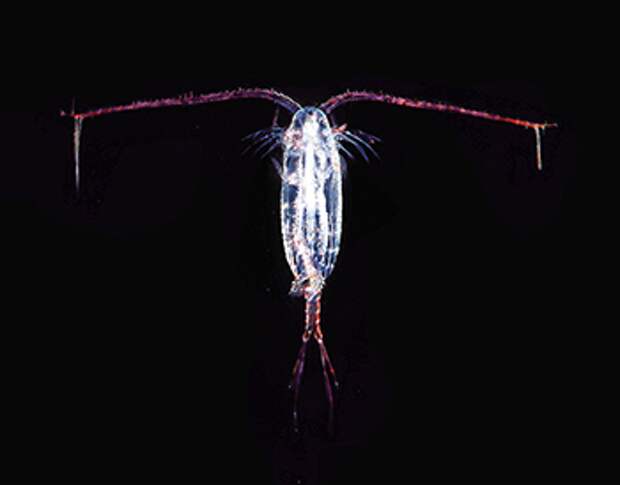

But Berge, Båtnes and their colleagues have found tiny creatures called plankton swirling in the dark ocean. Phytoplankton (FY-toh-plank-ton) — tiny ocean organisms that make food from the sun — aren’t active. But zooplankton (ZOH-plank-ton) — tiny animals that eat other plankton — don’t let the dark get them down.

When there is a regular day/night cycle over a period of 24 hours, hordes of tiny zooplankton called copepods (KOH-puh-podz) use the sun to time their exercise regimen. These tiny crustaceans cycle up and down in the water in a pattern called diel (Di-EEL) vertical migration. By day, the tiny critters descend into deep water. At night, they ascend back to the surface.

These daily laps are a matter of survival for the zooplankton. But this also makes them a dependable source of food that is “really attractive to predators,” Båtnes notes. “They’re full of fat,” she explains — “like energy bars.” In deep waters during the day, she notes, copepods are harder for predators to see. At night, it’s safer for the floating energy bars to surface and feed on the phytoplankton there.

When there’s no sunlight — like during the Arctic night — it might seem like the copepods should sink and…

The post Welcome to the Arctic’s all-night undersea party appeared first on FeedBox.