Author: Miss Cellania / Source: Neatorama

You probably know that the “D.C.” in Washington, D.C., stands for “District of Columbia” and that the district is not part of any state. But do you know why America’s Founding Fathers placed such importance on creating a capital outside of any state? We owe it all to piles of unpaid bills.

EVOLUTION OF THE REVOLUTION

In April 1783, the U.S. Congress (then known as the Continental Congress) gave preliminary approval to the Treaty of Paris, which, if ratified by both England and the United States, would end the Revolutionary War after eight long years of fighting. Final ratification was still a year off, but it was clear that the war was all but over and that the American colonies had won. That was good news for the colonies… but not necessarily for the soldiers who’d done the fighting, because it wasn’t clear that they would ever be paid for their years of service and sacrifice.

The Congress had run up huge debts to finance the war effort, and it had no real means of paying back the money. The Articles of Confederation, which served as the American constitution from 1781 until it was replaced by the U.S. Constitution in 1788, gave Congress the power to declare war and the power to raise an army to fight it. But it didn’t give Congress the power to levy taxes. Without this power, it had no way to raise the money it needed to pay its war debts. The Congress could ask the states to contribute, but it couldn’t compel them to do it. The states had run up huge war debts of their own that had to be repaid.

BEG, BORROW, STEAL

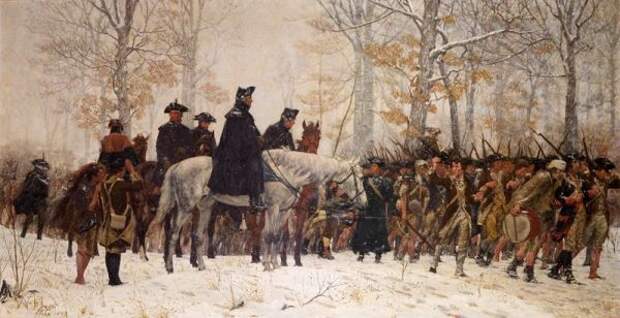

Many soldiers had been paid with IOUs or not at all. Their material needs had often gone unmet as well. During the winter of 1777, for example, nearly a quarter of the 10,000 soldiers camped at Valley Forge died there -not from combat, but from malnutrition, exposure, and disease. “We have this day no less than 2,873 men in camp unfit for duty because they are barefooted and otherwise naked,” General George Washington complained in a letter two days before Christmas in 1777.

FREE… FOR NOW

Soldiers with the means to do so had supported themselves during the war, and when their money ran out, they had amassed debts of their own. Now, having shed their blood to secure America’s liberty, they faced the prospect of losing their own liberty in debtors’ prison as soon as they were discharged from the army. “We have borne all that men can bear,” one group of soldiers wrote in a petition to Congress in early 1783, “our property is expended, our private resources are at an end.”

In response to this and other demands for payment from the soldiers, Congress could offer only vague promises to make good on its obligations to pay them …someday.

ON THE MOVE

On June 19, 1783, a group of about 80 unpaid soldiers stationed in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, mutinied and began marching the 60 miles to Philadelphia, then the nation’s capital, to demand payment from Congress in person. As they made their way toward the city, more troops abandoned their posts and joined the march. The congressmen, meeting at the State House (known today as Independence Hall), feared that if the soldiers made it to Philadelphia they’d join forces with soldiers stationed in the city. The mutiny might then be large enough to overthrow the government, ending America’s democratic experiment just as it was beginning.

Congress had no troops of its own to call on for protection. When the war ended, the Continental Army had disbanded, and command of the soldiers had reverted to the states, each of which had its own militia. Alexander Hamilton, then a congressman from New York, appealed to Pennsylvania’s ruling body, the Supreme Executive Council, to dispatch the state militia to protect Congress, but the council refused to do so. Unless and until the soldiers became violent, Congress would have to fend for itself.

By then, of course, it would probably be too late.

OVER THE LINE

Having been rebuffed by the Supreme Executive Council, Hamilton dispatched the assistant secretary of war, Major William Jackson, to meet with the soldiers at the city limits and hopefully turn them back. No such luck- the soldiers marched right past Jackson and, as feared, made common cause with troops stationed in the city. The mob, now numbering some 400 angry (and, thanks to the generosity of sympathetic tavern keepers, drunken) men, raided several arsenals and seized the weapons inside. Then it marched on the State House and surrounded it while Congress was meeting inside.

STANDOFF

The mutineers delivered a petition to Congress stating their demands and threatening that if they were not met within 20 minutes, the “enraged soldiery” would take matters into their own hands. As volatile as the situation was, Congress refused to submit to the soldiers’ demands, nor would it agree to negotiate with the mob or even adjourn for the day. Instead, it continued with its ordinary business for another three hours, then adjourned at the usual time and left the building to the taunts and jeers of the soldiers outside.

That evening Congress reassembled at the home of Elias Boudinot, the president of Congress. There it passed a resolution condemning the mutineers and demanding that Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council order the state militia to disperse the mob. If the Council refused, the Congress warned, it would leave the state and assemble in either Trenton or Princeton, New Jersey. And if Pennsylvania refused to guarantee the security of the congressmen in the future, it would never meet in the city again.

TIME TO GO

The next morning Alexander Hamilton and another congressman, Oliver Ellsworth, delivered the resolution to the president of the Supreme Executive Council, John Dickinson, in person. But Dickinson sympathized with the unpaid troops, and he feared that the Pennsylvania militia -also comprised of Revolutionary War veterans- would refuse to fire upon their brothers in arms if commanded to do so. Dickinson declined to take action.

With no help coming from the state government, Congress made good on its threat and evacuated to Princeton. It remained there for just a month before moving to Annapolis, Maryland. A year later, in 1785, it moved to New York City. It was still there in June 1788, when the U.S. Constitution replaced the Articles of Confederation. The new constitution gave Congress the power to levy taxes, which finally made it possible to pay its bills.

STAND DOWN

By then, of course, the mutiny was long over. Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council eventually did call up the state militia to disperse the mutineers, and as soon as the soldiers received word that the militia was on its way, they laid down their arms and returned to their bases. They never fired a shot or killed a single person in anger, which is one of the reasons the “Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783” is largely forgotten today.

But the mutiny did have a big impact on American history, because the congressmen who found themselves surrounded by an armed, angry (and drunken) mob with no one coming to their aid were determined that the fledgling democracy would never face such a threat again. “The Philadelphia mutiny… gave rise to the notion that the national capital should be housed in a special federal district where it would never stand at the mercy of state governments,” author Ron Chernow writes in his biography of Alexander Hamilton. When delegates met in 1787 (in Pennsylvania’s State House, ironically) to draft the new constitution, they inserted in Article 1, Section 8, of the U.S. Constitution a paragraph giving Congress the power “…to exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of Particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States.”

DETAILS, DETAILS, DETAILS

The U.S. Constitution did not, however, say where the capital city should be located or even require that one be established. All it said was that such a city could be created, and if it was, that Congress would exercise exclusive control over it, including providing for its security. Whether such a city would be built -and if so, where- would be the subject of battles to come.

SITE FIGHT

The U.S. Constitution did not require that a new…

The post How a Pile of Unpaid Bills Led to Washington, D.C. appeared first on FeedBox.