Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

I have worried, and continue to worry, that we have relinquished the reflective telescopic perspective for the reactionary microscopic perspective. When we surrender the grandest, often unanswerable questions to the false certitudes of the smallest, we lose something essential of our humanity.

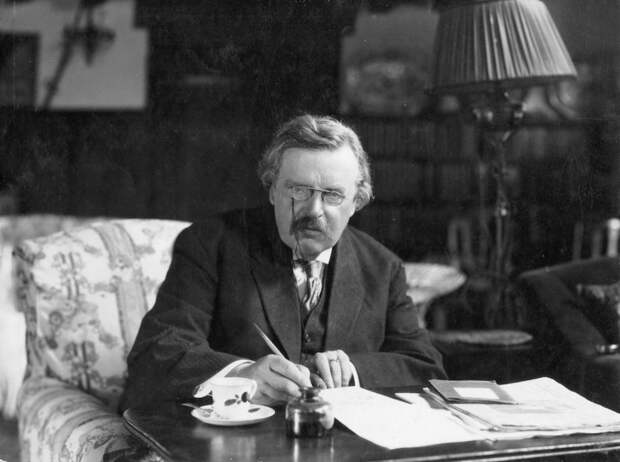

When we aim the spears of those certitudes at one another, more interested in being right than in understanding, we lose something essential. How did we get to a place where to have an opinion is more culturally rewarded than to have a question? Hannah Arendt admonished against this dehumanizing loss decades ago in her trailblazing Gifford lecture on the life of the mind: “To lose the appetite for meaning we call thinking and cease to ask unanswerable questions [would be to] lose not only the ability to produce those thought-things that we call works of art but also the capacity to ask all the answerable questions upon which every civilization is founded.”How to guard against the decivilizing tyranny of unthinking opinion over perspectival thought is what the English poet, essayist, philosopher, dramatist, journalist, and art critic G. K. Chesterton (May 29, 1874–June 14, 1936) — an imperfect man, to be sure, but also a brilliant one belonging to that rare species of truth-seers — addressed in the opening chapter of his 1905 essay collection Heretics (free ebook | public library).

Writing decades before philosopher Simone Weil contemplated the dangers of our self-righteous for and against, Chesterton — who feasted on paradox and employed a style of rhetoric he called “uncommon sense,” subverting popular arguments to reveal their deficiencies — writes:

In former days… the man was proud of being orthodox, was proud of being right… The word “orthodoxy” not only no longer means being right; it practically means being wrong. All this can mean one thing, and one thing only. It means that people care less for whether they are philosophically right.

[…]

It is foolish, generally speaking, for a philosopher to set fire to another philosopher in Smithfield Market because they do not agree in their theory of the universe. That was done very frequently in the last decadence of the Middle Ages, and it failed altogether in its object. But there is one thing that is infinitely more absurd and unpractical than burning a man for his philosophy. This is the habit of saying that his philosophy does not matter.

Chesterton laments that in the exponential narrowing of focus toward more and more hard-held opinions about smaller and smaller dimensions of life, we have increasingly lost perspective — that telescopic perspective — of the largest, most enduring, most important questions of existence. He writes:

Atheism itself is too theological for us to-day. Revolution itself is too much of a system; liberty itself is too much of a restraint. We will have no generalizations… A man’s opinion on tramcars matters; his opinion on Botticelli matters; his opinion on all things does not matter. He may turn over and explore a million objects, but he must not find that strange object, the universe; for if he does he will have a religion, and be lost. Everything matters — except everything.

Chesterton — who vehemently and publicly opposed eugenics when Britain was passing the Mental Deficiency Act and considering sterilizing the mentally ill — admonishes against the perils of surrendering the grand perspective. Noting that “the human brain is a…

The post Perspective in the Age of Opinion: Timely Wisdom from a Century Ago appeared first on FeedBox.