Author: Joshua Sokol / Source: WIRED

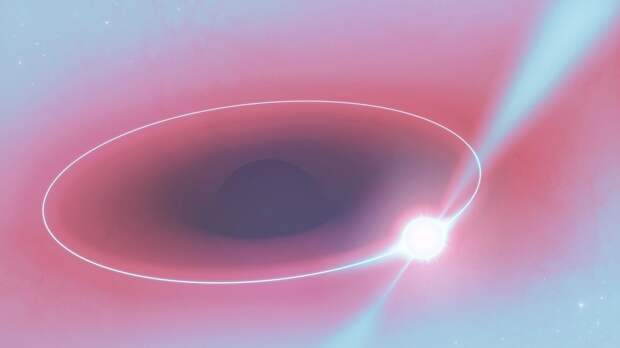

For the first time, scientists have spotted something wobbling around the black hole at the core of our galaxy. Their measurements suggest that this stuff—perhaps made of blobs of plasma—is spinning not far from the innermost orbit allowed by the laws of physics.

If so, this affords astronomers their closest look yet at the funhouse-mirrored space-time that surrounds a black hole. And in time, additional observations will indicate whether those known laws of physics truly describe what’s going on at the edge of where space-time breaks down.Astronomers already knew that the Milky Way hosts a central black hole, weighing some four million suns. From Earth, this black hole is a dense, tiny thing in the constellation Sagittarius, only as big on the sky as a strawberry seed in Los Angeles when viewed from New York. But interstellar gas glows as it swirls into the black hole, marking the dark heart of the galaxy with a single, faint point of infrared light in astronomical images. Astronomers call it Sagittarius A* (pronounced “A-star”).

For 15 years researchers have watched that point flicker—and wondered why. Occasionally, it flares up 30 times brighter in infrared light and then subsides, all within just a few minutes. Now, though, a team based at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, Germany, has measured not just this speck’s brightness but its position with staggering precision. When it flares, it also moves clockwise on the sky, tracing out a tiny circle, they find.

“They have clearly seen something moving,” said Shep Doeleman, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who did not participate in what he calls the team’s “extraordinary” measurements, which was published this week in Astronomy & Astrophysics. “What it is, is not exactly clear.”

But one particular interpretation stands out, the team argues. This wobbling likely comes from “hot spots,” glowing blobs of magnetically heated plasma orbiting right above the black hole’s gaping maw at almost one-third the speed of light. As these hot spots circle, the black hole’s immense gravitational forces twist space-time itself into something like a lens, one that flashes beacons of light across the cosmos like a galactic searchlight beam. The idea, first proposed in 2005 by Avery Broderick, now at the Perimeter Institute of Theoretical Physics and the University of Waterloo in Canada, and Avi Loeb of Harvard University, would explain why the black hole appears to flare.

“It seems like they’ve got something really exciting here,” added astronomer Andrea Ghez, a longtime competitor to the European team at the University of California, Los Angeles.

If these rotating flares are due to hot spots in the way that Broderick and Loeb imagined, additional flares will help reveal the black hole’s “spin,” a measure of its rotation. And it could also provide a new way to poke and prod Einstein’s theory of general relativity in the flexed space-time at the mouth of a black hole.

“To occasionally be right makes up for all the other times when I scratched my head at the blackboard,” said Broderick. “This is what makes being a scientist so much fun.”

Since the 1990s, Ghez’s group at UCLA and the European team, led by Reinhard Genzel of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, Germany, have used ever-sharper techniques to resolve the orbits of stars right around the galactic center. Earlier this summer, Genzel’s team published a measurement of how general relativity is affecting the light of a star now passing close to the black hole; a similar paper by Ghez’s team is now under review. “It’s a remarkable moment, in terms of these experiments’ ability to start probing how gravity works near a supermassive black hole,” Ghez said.

But since last year, the European team has had a unique tool—the power of four giant telescopes working together in a project called GRAVITY. On a typical night, the European Southern Observatory’s four 8-meter telescopes on Cerro Paranal, overlooking Chile’s Atacama desert, loll in different directions on the sky. GRAVITY pulls them together using a technique called interferometry that combines observations from multiple telescopes to produce artificial images that only a preposterously huge real telescope could make.

To do this in infrared wavelengths—close to what human eyes can perceive—requires blending light in real time to avoid losing crucial information. So on July 22, when Sagittarius A* flared, the light collected by each scope traveled through a Rube Goldberg–like setup of mirrors and fiber-optic cables that traced out a path with…

The post Astronomers Creep Up to the Edge of the Milky Way’s Black Hole appeared first on FeedBox.