Author: Jessica Leigh Hester / Source: Atlas Obscura

Several thousand years ago, in Babylonia, someone chiseled columns of text onto a tablet that set down instructions for what people might expect on any given day of the year. Some boded well—the first day of the new year was “completely favorable,” with good luck at every turn—while others called for caution.

Twelve days in, it was dicey to barter grain, two days after that was prime time to bring up legal woes, and three days later, according to the inscription, doctors should dodge their patients. Consulting each day’s forecast could be difficult if you were out and about—but eventually, people found a way to take their information and prognostications with them wherever they went.The Babylonian Almanac is among the earliest texts to lay out such daily prescriptions and predictions. From there, the format took off. By the early modern era, Europeans were eager to know how to carpe the heck out of each diem, and when to evade danger by laying low. In the pages of almanacs, readers found calendars and counsel—everything from reminders about religious feast days to details of the lunar cycle, according to Cambridge historian Lauren Kassell. Readers snapped up these volumes in huge numbers. During the Renaissance, historian Bernard Capp has noted, English almanacs sold some 400,000 copies a year—bested only, perhaps, by the Bible.

Each almanac had a shelf life, though—precisely 365 days. By and large, Kassell has written, they were ephemeral, “discarded in December, used to light a fire or tossed down the privy.

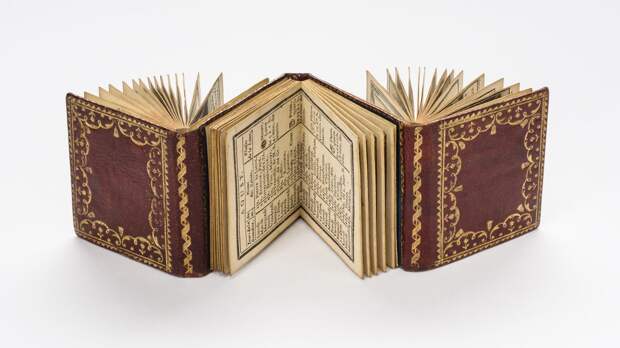

” Each January, you’d grab a fresh edition for a new set of forecasts and factoids and everything you needed to know for the months ahead.Despite this, some of these volumes were made with striking craftsmanship and dazzling details. An untold number were deliciously, ostentatiously, really, really small—made for people with nimble fingers, impeccable eyesight, and deep pockets.

Almanacs of any size had the appeal of putting information right at your fingertips, and the smaller versions—some as tiny as a postage stamp—added the allure of ultimate portability. It’s hard to say exactly when miniature almanacs emerged, but a bibliography of miniature books compiled by former Newberry cataloger Doris Varner Welsh lists a calendar for the year 1475, made in Trent, as an early example. (That one held six leaves and measured roughly three inches by two inches.) Suzanne Karr Schmidt, curator of rare books and manuscripts at the Newberry Library in Chicago, describes these volumes…

The post For Centuries, Know-It-Alls Carried Beautiful Miniature Almanacs Wherever They Went appeared first on FeedBox.