Author: Jessica Leigh Hester / Source: Atlas Obscura

Lisa McKeon remembers the moment it happened. She was eating a bagel with cream cheese when she heard it: a thundering crack, followed by a splash.

The sound reverberated off the basin’s walls of sedimentary rock.McKeon is a physical scientist at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center (NOROCK), stationed in West Glacier, Montana. She spends a lot of time in the field in Glacier National Park. That afternoon last month, though, she was off the clock—picnicking with her 13-year-old daughter on the smooth rocks 50 yards from the shore of Upper Grinnell Lake, a body of meltwater at the terminus of Grinnell Glacier. “I wanted to bring her to a place I have been going to since I was her age,” McKeon says.

McKeon goes out to Grinnell a few times a year, and some things never seem to change. It’s always cold there—enough so that, when the wind whips off the ice, carrying the smell of wet dirt, she has to pull on every layer of clothing she stuffed into her backpack, no matter the season. The ice, embedded with little pebbles and bits of rock, always pops underfoot when she gets up close to measure Grinnell’s margins. The glacier itself is always loud. While these ice giants may look static, active glaciers are perpetually on the move. They creak and moan; inside, water courses through rivulets and tunnels. These can be so deep in the ice that they seem invisible—still, you can hear the rushing.

But in all her time around glaciers, McKeon had never heard a sound like this. Even so, “I knew exactly what was happening,” she says. The glacier was calving.

She didn’t see the fracture, but when she heard the inescapable, unmistakable sound, McKeon turned her gaze to the water. “You couldn’t see any waves across the top, but [the water level] started rising,” she says. “Icebergs were sloshing back and forth.”

Glaciers calve—it’s part of their natural life cycle—but in a warming world, it is happening more often. In July, a tremendous iceberg separated from a glacier near Greenland’s west coast and bobbed over to Innaarsuit. Residents evacuated the small fishing village as more than 10 million tons of ice loomed just offshore. The behemoth was a harbinger. “As things continue to warm up, more ice is gonna come off and float around,” Joshua Willis, a glaciologist from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, told The New Yorker at the time.

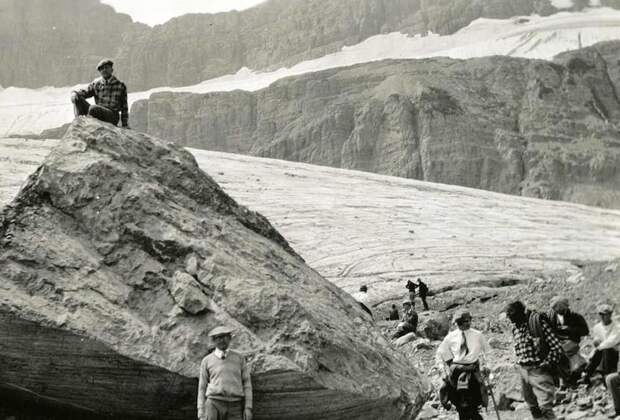

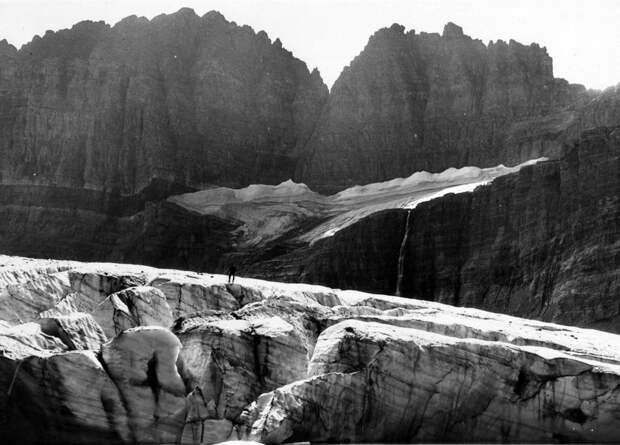

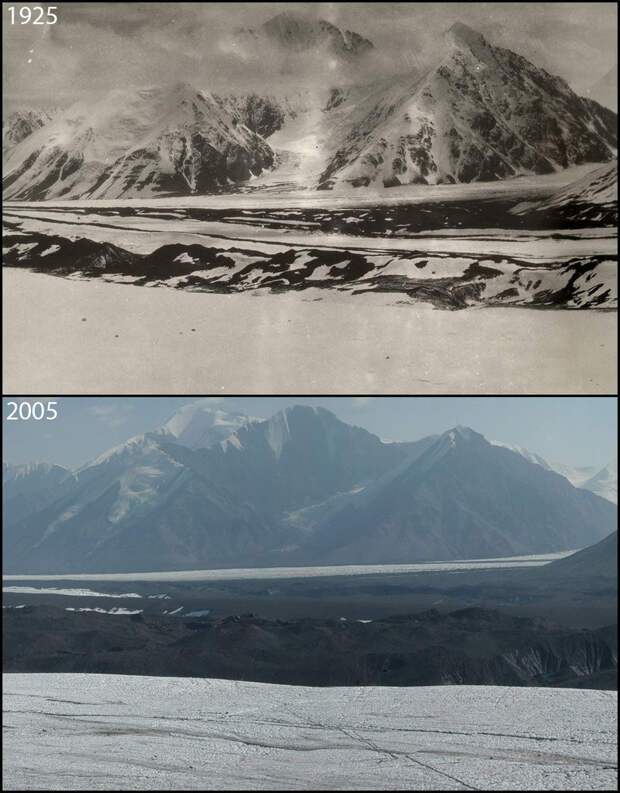

In addition to that falling ice, glaciers are losing bulk to melt, too. It’s already happening at Grinnell. In one picture from 1938, the glacier is so huge and richly marbled that it’s easy to miss the person standing atop it. (The first hint is two tiny, dark shoes against the large expanse of white.) By 2016, there was nothing left to summit—where the figure had stood, the ice had given way to water.

That is the other thing that now stays the same at Grinnell, year after year—loss. Climate change is coming for glaciers, and the national parks as a whole. It’s coming fast. We can’t shield all of these protected areas from the future we have given them. So then what? What’s Glacier National Park without its famous ice?

The iconic landscapes of America’s national parks occupy potent places in the cultural imagination—and they can make for stunning demonstrations of the impacts of climate change. That’s not only because the parks are so familiar, but also because, compared to the rest of the country, they are being hit particularly hard.

That’s the thrust of a new paper from researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In the journal Environmental Research Letters, the authors report the results of the first survey measuring both historical temperatures and rainfall across all 417 sites in the system—parks, battlefields, monuments, and more—alongside projections for future changes under various emissions forecasts. The researchers found that, between 1895 and 2010, the land within the parks has warmed at double the rate of the rest of the country. Meanwhile, precipitation in the parks has decreased by 12 percent, as opposed to the 3 percent average across the rest of the United States.

Some difference between the parks and the rest of the country isn’t entirely surprising, because so much of the parks’ total area is baldly exposed, at high elevations or northern climes, where warming occurs most dramatically. (Sixty-three percent of total national park area is in Alaska; 19 percent is above the Arctic Circle.) As snow melts, the landscape it once blanketed loses its reflective properties, and absorbs more heat. Even if the pattern was predictable, “the magnitude of the difference was not expected,” says lead author Patrick Gonzalez, a forest ecologist at Berkeley.

In the years between 1950 and 2010, Denali National Park and Preserve, in Alaska, warmed most of all. The authors report that Denali’s temperatures rose by 4.3°C over the last few decades, which squares fairly neatly with the National Park Service’s own measurement of 4°C.

The authors project that curbing greenhouse gas emissions could cushion future blows. “Cutting emissions can save parks from the…

The post Climate Change Is Coming for America’s National Parks appeared first on FeedBox.