Author: Alexandra Witze / Source: Science News

Every autumn, a quiet mountain pass in the Swiss Alps turns into an insect superhighway. For a couple of months, the air thickens as millions of migrating flies, moths and butterflies make their way through a narrow opening in the mountains. For Myles Menz, it’s a front-row seat to one of the greatest movements in the animal kingdom.

Menz, an ecologist at the University of Bern in Switzerland, leads an international team of scientists who descend on the pass for a few months each year. By day, they switch on radar instruments and raise webbed nets to track and capture some of the insects buzzing south. At sunset, they break out drinks and snacks and wait for nocturnal life to arrive. That’s when they lure enormous furry moths from the sky into sampling nets, snagging them like salmon from a stream. “I love it up there,” Menz says.

He loves the scenery and the science. This pass, known as the Col de Bretolet, is an iconic field site among European ecologists. For decades, ornithologists have tracked birds migrating through. Menz is doing the same kind of tracking, but this time, he’s after the insects on which the birds feast.

Migrating insects, like those that zip through the Swiss mountain pass, provide crucial ecosystem services. They pollinate crops and wild plants and gobble agricultural pests.

“Trillions of insects around the world migrate every year, and we’re just beginning to understand their connections to ecosystems and human life,” says Dara Satterfield, an ecologist at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

Scientists like Menz are fanning out across the globe to track butterflies, moths, hoverflies and other insects on their great journeys. Among the new discoveries: Painted lady butterflies time their round trips between Africa and Europe to coincide within days of their favorite flowers’ first blossoms. Hoverflies navigate unerringly across Europe for more than 100 kilometers per day, chowing down on aphids that suck the juice out of greening shoots. What’s more, some agricultural pests that ravage crops in Texas and other U.S. farmlands are now visible using ordinary weather radar, giving farmers a better chance of fighting off the pests.

Until now, most studies of animal migration have focused on large, easy-to-study birds and mammals. But entomologists say that insects can also illuminate the phenomenon of mass movement. “How are these animals finding their way across such large scales? Why do they do it?” asks Menz. “It’s really quite fantastic.”

| |

| NOTHING BUT NET Butterflies, hoverflies and other migrating insects poured across the Col de Bretolet pass in the Swiss Alps on this day in September 2016. Researchers based at the University of Bern captured, marked and released red admiral (Vanessa atalanta) butterflies as part of a project, including citizen-science efforts, to track this migrating species. |

To warmer worlds

Animals migrate for many reasons, but the aim is usually to eat, breed or otherwise survive year-round. One of the most famous insect migrations, of North America’s monarch butterflies (Danaus plexippus), happens when the animals fly south from eastern North America to overwinter in Mexico’s warmer setting. (A second population from western North America overwinters in California.) In Taiwan, the purple crow butterfly (Euploea tulliolus) migrates south from northern and central parts of the island to the warmer Maolin scenic area every winter, where the butterfly masses draw crowds of lepidopteran-loving tourists. In Australia, the bogong moth (Agrotis infusa) escapes the hot and dry summer of the country’s eastern parts by traveling in the billions to cool mountain caves in the southeast.

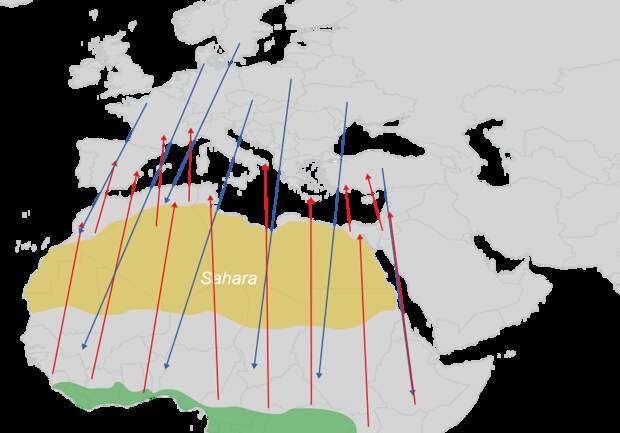

The migrations can be arduous. Each spring, the painted lady butterfly (Vanessa cardui) moves out of northern Africa into Europe, crossing the harsh Sahara and then the Mediterranean Sea before retracing the route in the autumn (SN Online: 10/12/16). Because adult life spans are only about a month, the journey is a family affair: Up to six generations are needed to make the round trip. It’s like running a relay race, with successive generations of butterflies passing the baton across thousands of kilometers.

Constantí Stefanescu, a butterfly expert at the Museum of Natural Sciences in Granollers, Spain, has been tracking the painted lady migrations. He relies on citizen scientists who alert him when the orange-and-black-winged painted ladies arrive in people’s backyards each year, as well as field studies by groups of scientists. In 2014, 2015 and 2016, Stefanescu led autumn expeditions to Morocco and Algeria to try to catch the return of the painted ladies to their wintering grounds.

By surveying swaths of North Africa, Stefanescu’s team confirmed that the painted ladies virtually disappeared from the area during the hot summer months and returned in huge numbers in October. The fliers arrived back in Africa just in time to feed on the daisylike false yellowhead (Dittrichia viscosa) and other flowers. The findings make clear how well the butterflies are able to time their migrations to take advantage of resources, Stefanescu reported in December in Ecological Entomology.

Painted lady butterflies embark on one of the world’s most distinctive migrations, traveling thousands of kilometers from Africa into Europe each spring, and back again in the fall. It can take six generations of butterflies to make the round trip journey.

Other insect species are less visibly stunning than the painted lady, but just as important to the study of migrations. One emerging model species is the marmalade hoverfly (Episyrphus balteatus), which migrates from northern to southern Europe and back each year.

Marmalade hoverflies have translucent wings and an orange-and-black striped body. As larvae, they eat aphids that would otherwise damage crops. As adults, the traveling hoverflies help pollinate plants. “They’re useful for so many things,” says Karl Wotton, a geneticist at the University of Exeter in England.

Wotton started thinking about the importance of insect migration after 2011, when windblown midges carried an exotic virus into the southern United Kingdom that caused birth defects in cattle on his family’s farm. Intrigued, Wotton set up camp at a spot in the Pyrenees at the border of Spain and France to study migrating hoverflies. Then he heard that Menz was doing almost exactly the same kind of research at the Col de Bretolet and a neighboring pass. The two connected, hit it…

The post Flying insects tell tales of long-distance migrations appeared first on FeedBox.