Author: Rowan Kaiser / Source: VentureBeat

The following is an excerpt from Chapter 5 of The Secret History of Mac Gaming, “Simulated.”

In 1985, at the suggestion of a neighbor from across the street, professional city planner Bruce Joffe, Will Wright began to expand the program he’d made for creating and editing the background graphics in his popular Commodore 64 helicopter game Raid on Bungeling Bay.

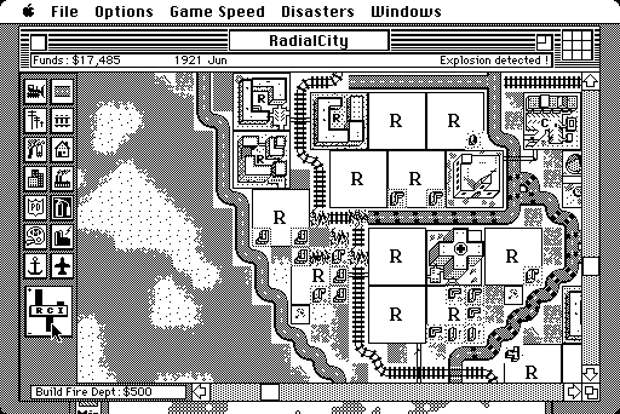

This editing program could paint the play area, tile by tile, with water, land, shoreline, roads, buildings, and so forth, and Wright and Joffe had noticed that it was fun just to create cities with it.Wright read widely on urban planning and computer modeling theories and incorporated these ideas into the simulation he laid on top of the tile editor. In particular he was drawn to the work of MIT professor Jay Forrester, who conceived the theory of system dynamics — which shows how complex systems evolve through multiple interdependent internal feedback loops. “Micropolis”, as he called it, became a city-building and management simulator with power plants, roads, rail, police and fire departments, and three types of zoning: residential, industrial, and commercial.

At some point during development he ran out of memory on the Commodore 64 and switched to the more powerful Macintosh. (Out of pragmatism more than idealism, Mick Foley, his teenage neighbor from the time, explains: “DOS had great market share but bad graphics and no user interface support, while Amiga and Atari ST had no market share.”) Here he continued to improve the underlying simulation, utilizing the Mac’s greater horsepower. More significantly, he reworked the interface.

On Commodore 64, “Micropolis” had been a full-screen game controlled entirely with a keyboard and its palette of tools was laid out at the bottom of the screen. On Mac, it became a windowed application with mouse control, a MacPaint-inspired tool palette and menu system, and a separate window for the mini-map. It was, in essence, an interactive paint program — a MacPaint for city building. As the player painted her city on the canvas, its population would fall and rise and its visual appearance would evolve before her eyes. Its roads would come to life with traffic, its busiest districts patrolled by a helicopter, and its residents would build (or sometimes abandon) homes and businesses.

Underlying the game was a rough approximation of how cities work. Growth was tied to the attractiveness of different zones, which emerged from both a proximity to and distance from other zones (people don’t like to live too close to industry, but they also don’t like long commutes). It took shortcuts to work around the limitations of the technology. A city might require multiple power plants to meet its power needs, but only one of those plants actually needed to be connected to the power grid. Police and fire stations needed only one tile of road or rail adjacent to them to function. Most processes in the simulation operated on a delay, too — what Chaim Gingold, an expert on the game’s (now publicly available) code, calls a kind of polyrhythm of activity, as the system cycled through different processes to keep the city looking alive and ever-changing.

Few players noticed any of this, however. SimCity, as it was rechristened for release in 1989, captured the public’s imagination like no game ever had. Everybody knew what it was, even if they weren’t into video games. Will Wright became a minor celebrity, hailed as a genius for inventing this new genre of simulation. He and his colleagues at Maxis used it as the foundation for a whole Sim-flavored franchise — SimEarth, SimAnt, SimLife, SimCity 2000 (all developed on a Mac but released across multiple platforms), SimFarm, and many others — that would influence the entire industry.

SimCity made a particularly great impact on Japanese Macintosh enthusiast Yutaka “Yoot” Saito. He felt the Nintendo Entertainment System games he had played before SimCity were more suitable for kids. They had bright, colorful graphics and animation and cute, synthesized sounds, and they tended to be fast-paced. What they…

The post The Secret History of Mac Gaming: How SimCity led to Seaman appeared first on FeedBox.