Author: Jessica Leigh Hester / Source: Atlas Obscura

Robert McCracken Peck was looking for a free way to furnish his largely empty apartment. Instead, he ended up saving one of the world’s preeminent collections of hair from tumbling into obscurity.

It was 1976, and Peck was newly installed as an assistant to the director of the museum at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University, in Philadelphia. He happened to start his new position on the cusp of an office move. As he fumbled his way through confusing corridors, crowded with things to haul or toss, Peck passed a few tin boxes full of cast-off papers waiting to go to the dump. Stacked, he thought, the containers might make a nice bedside table.

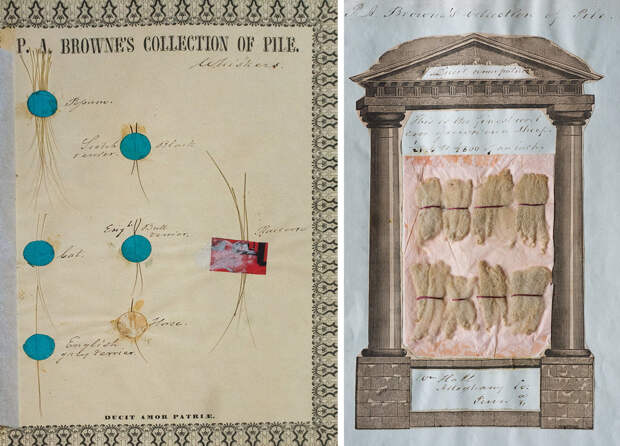

When he cracked the boxes open, though, he discovered scrapbooks full of hair—from famous people, from animals, from everyday folks from all walks of life. The samples were covered with tissue paper; flanked by correspondence, sketches, and detailed handwritten annotations; and encased by ornate endpapers. Their contents were “a little bit brittle, had yellowed a little bit, and oils from hair had transferred over to opposing pages,” says Peck, who is now a senior fellow at the Academy.

“Otherwise, not much deterioration had occurred—it had not been exposed to light.”At the time he thought there had to have been some mistake. Surely this unusual collection wasn’t intended for the trash. But other staffers were much less enthused about the find than he was, and were eager to get the curiosity off their hands. One told Peck that the albums were a little icky and lacking in scientific value—but Peck found them meticulous and compelling. He asked to become their custodian. “I returned to the hallway discards and with a large black marker boldly added NOT above the word TRASH scrawled at the top of the scraps of paper taped to each box,” he recounts in Specimens of Hair: The Curious Collection of Peter A. Browne, a new book about the collection.

Peck then spent years unraveling the history of this hirsute hodgepodge.

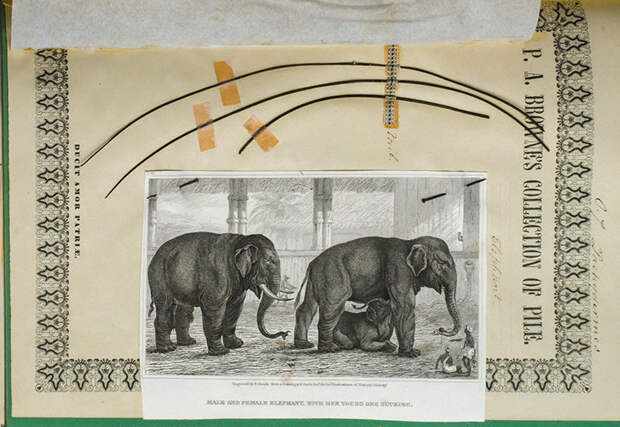

For a guy who didn’t breed or keep sheep, Peter A. Browne sure knew a lot about them—especially their wool. From the 1840s to the 1860s, he studied one strand after another in near-forensic detail. He built a contraption to test their elasticity, and measured them against hairs from a sloth, elk, grizzly, and “elephant’s beard.” He enumerated the differences between “hairy” and “wooly” sheep so convincingly that agricultural societies considered his insights essential, and he traveled from America to England to lecture on textile manufacturing.

A naturalist with a roving, rambling curiosity, he studied geology and botany before…

The post The Strange Allure of Hundreds of Samples of Hair appeared first on FeedBox.