Author: Tory Bilski / Source: Atlas Obscura

Herring can be brined, smoked, or pickled in vinegar, brought to your table as matjes, kippers, or if you’re lucky, marinated in cream by Zabar’s deli on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Today the fish is automatically processed by fillet and brining machines.

But up until a half a century ago, the process had historically been done by hand, specifically female hands.They were called Herring Girls in the North Atlantic countries—places such as the Scottish Shetlands and Outer Hebrides, the Danish Faroe Islands, and Iceland. They were the women who processed the fishermen’s catch, standing for long hours on the piers, sorting, chopping, filleting the herring before brining and packing them in barrels. Like flocks of gulls, these women followed the fish supply to the cold-water ports where the Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) were so plentiful that a massive school could contain more than a billion fish.

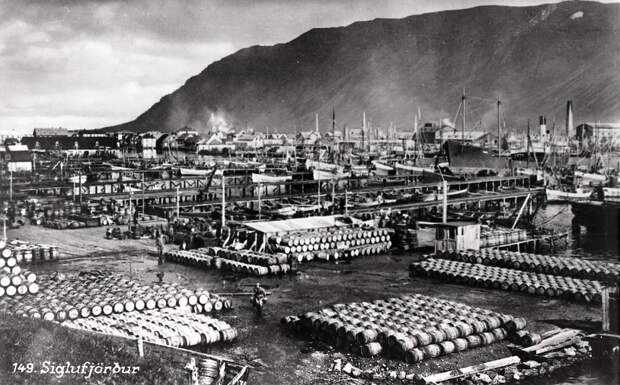

In Iceland, from the 1910s through the 1960s, the herring industry was an economic life-raft for a far north Atlantic island nation burdened for centuries with food scarcity, inclement weather, and lack of a cooperative growing season. Before, during and after the world wars, Siglufjörður was the capital of the herring industry, accounting for 25-45 percent of total export earnings. During its heyday, this small town at the northern tip of a very northern fjord jutting out to the Greenland Sea was home to Iceland’s equivalent of the gold rush.

Herring is a highly perishable fish and the loads were large. The industry flourished because while the men fished the seas, coopered barrels, and worked in the fish meal factories, the women were needed to do the fast work of preserving the fish before it spoiled. From all over Iceland, women came to Siglufjörður from their small towns and family farms for the opportunity to make money.

“During the 1930s, an active herring girl could earn as much as $10 a day,” says Anita Elefsen, Director of the Herring Era Museum in Siglufjörður. “Each girl gutted and packed their own barrel. After filling a barrel, a token was put in their boots, and the tokens were then exchanged for receipts at the end of the workday. Once a week they were paid out with cash.”

Margret Thoroddsdottir was born in Siglufjörður and worked for nine summers as a herring girl. She started when she was 14 in the summer of 1951. “As soon as the boats came in the girls were called to work. If it was at night, we were awakened by callers who had that specific duty. They would shout loudly, ‘Get up, get up – the herring has arrived!‘”

The work was hard, Elefsen says. “Since they were paid by the barrels, they competed with time to accomplish as much as possible every single work day, to earn as much as they could.”

“Depending on the catch, we would work all night if we had to,” says Thoroddsdottir. “Sometimes the work lasted for more than 24 hours straight.”

But then, these…

The post The Busy, Briny Lives of Iceland’s Herring Girls appeared first on FeedBox.