Author: Jessica Leigh Hester / Source: Atlas Obscura

On recent evenings, as July has melted into August, Earth’s rocky red companion has dropped by for a visit. Earth and Mars, when they’re on opposite sides of the Sun, can be as many as 250 million miles apart. This week, however, Mars has been just shy of 36 million miles from Earth, the snuggest our planets have been since 2003. Looming bright and orange in the night sky, it has been easily visible to the naked eye. The close-up comes courtesy of opposition—the point at which Mars, Earth, and the Sun align, with us sandwiched in the middle.

When the planets approached a similarly cozy distance 94 years ago, in August 1924, some people, including Curtis D. Wilbur, the Secretary of the U.S. Navy, thought it might be possible to actually hear message from our neighbor. If Martians were ever going to drop us a line, they suspected, that’d be the time.

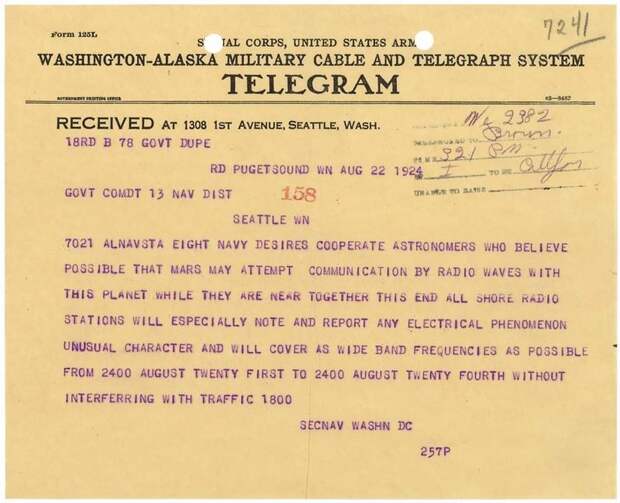

From an office in Washington, D.C., Wilbur’s department sent orders to every naval station clear across the country. An outpost in Seattle received a telegram asking operators to keep their ears tuned to anything unusual or, maybe, otherworldly.

“Navy desires [sic] cooperate [sic] astronomers who believe [sic] possible that Mars may attempt communication by radio waves with this planet while they are near together,” it read. “All shore radio stations will especially note and report any electrical phenomenon [sic] unusual character …” The orders asked for operators to keep the lines open and carefully manned between August 21 and August 24, just in case.

This request didn’t come out of nowhere. There was a long buildup to the idea that Mars might be trying to tell us something, with technologies that were then new to us. As early as 1894, Sir William Henry Preece, the top engineer at the British General Post Office and a champion of radio and wireless technology, proposed that it might be possible to ring up our planetary neighbor. Say Mars was populated “with beings like ourselves having the gift of language and the knowledge to adapt the great forces of nature to their wants,” he wrote.

And imagine that those fluent, expressive beings had managed to “oscillate immense stores of electrical energy to and fro in electrical order.” Under those conditions, Preece said, he saw no reason why it wouldn’t be possible “to hold communication, by telephone, with the people of Mars.”It was far-fetched, sure, but it probably didn’t strike readers as unthinkable. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the popular press was enamored of the idea that Mars was neither unknowable nor utterly alien. In Atlantic Monthly, astronomer Percival Lowell suggested that Martians were dredging a series of canals on their planet, which looked fairly similar to ones freshly dug out on Earth. Scientific American and a slew of university professors nodded in agreement. (We now know they are natural features.) And in…

The post Everybody Shut Up! We’re Listening to Mars appeared first on FeedBox.