Author: Aida Alami / Source: New York Times

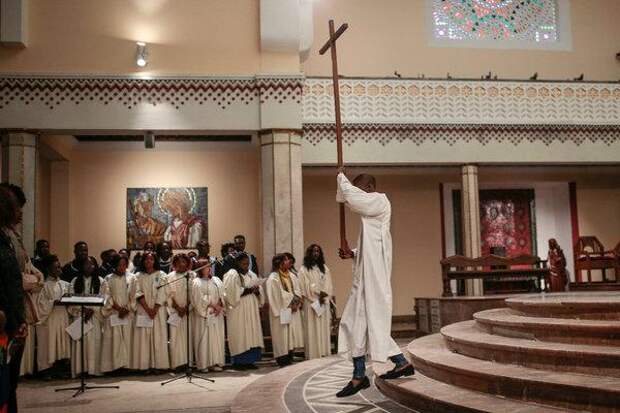

Fadel Senna/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

MEKNES, Morocco — On a Monday evening in a ground-floor apartment shielded from the street by heavy yellow curtains, five people stood around a table in the living room as a woman read from a pink leather-bound Bible in Arabic.

Holding hands, they prayed and read psalms, as a mandolin player accompanied their chants and a 2-year-old girl hit a ball playfully against the pink walls.

They would prefer to worship in a church, but as Moroccans and former Muslims who converted to Christianity, they are compelled to hide their activities from public sight.

Morocco, where Pope Francis will arrive on Saturday for a visit, is widely perceived to be an unusually tolerant Muslim country. And to a certain extent, it is.

It is the only Arab country that constitutionally guarantees recognition of its Jewish population, granting it separate laws and courts to regulate matters related to family law. It also regularly organizes events to promote interfaith dialogue and has ratified international treaties guaranteeing religious freedom. The foreign-born, largely Westerners and immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa, can worship openly.

Moroccans, 99 percent of them Sunni Muslims, cannot freely express atheistic beliefs or conversion to another faith. Criticizing Islam remains extremely sensitive, and worship for indigenous Christians, who number somewhere between 2,000 and 50,000, is problematic, particularly for those who converted from Islam.

Moroccan Christians have long been ostracized, sometimes rejected by society and closely scrutinized by the state. They are not officially banned from churches. But to practice their faith openly is to invite harassment and threats, even — or especially — from relatives.

While almost no one is being arrested because of their beliefs these days, most feel constrained from freely attending churches and publicly performing rituals like baptisms, weddings and funerals in accordance with their beliefs. But priests and pastors face possible accusations of proselytizing, a crime in Morocco, simply by having Moroccans attend Mass.

Voluntary conversion, while stigmatized, is not technically illegal. Evangelism is. Morocco has expelled dozens of foreigners suspected of proselytizing, or “shaking the faith of a Muslim.” In 2010, the Village of Hope orphanage in the Middle Atlas Mountains was shut down on suspicion that it was teaching Christianity to the children.

Attention to the plight of Morocco’s Christian converts is getting some traction ahead of Pope Francis’ arrival, as they seize the opportunity to advocate greater freedom to worship.

“We believe that any interreligious dialogue and any fight against extremism can succeed only on the basis of a total frankness on the issue of religious freedom for Moroccan citizens, including Christian Moroccans,” said a statement by the Coordination of Moroccan Christians, a local advocacy group. “We hope that the visit of the Holy Father will be a historic opportunity to move our country forward in this direction.”

The group that meets behind curtains in Meknes wants not only to worship in broad daylight, but to do so in the places of their choosing.

“I want to name my daughter Easter and…

The post Pope Francis’ Visit to Morocco Raises Hopes for Its Christians appeared first on FeedBox.