Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

“To create today is to create dangerously,” Albert Camus wrote in the late 1950s as he contemplated the role of the artist as a voice of resistance. “In our age,” W.H. Auden observed around the same time across the Atlantic, “the mere making of a work of art is itself a political act. ” This unmerciful reality of human culture has shocked and staggered every artist who has endeavored to effect progress and lift her society up with the fulcrum of her art, but it is a fundamental fact of every age and every society. Half a century after Camus and Auden, Chinua Achebe distilled its discomfiting essence in his forgotten conversation with James Baldwin:

Those who tell you “Do not put too much politics in your art” are not being honest. If you look very carefully you will see that they are the same people who are quite happy with the situation as it is… What they are saying is don’t upset the system.

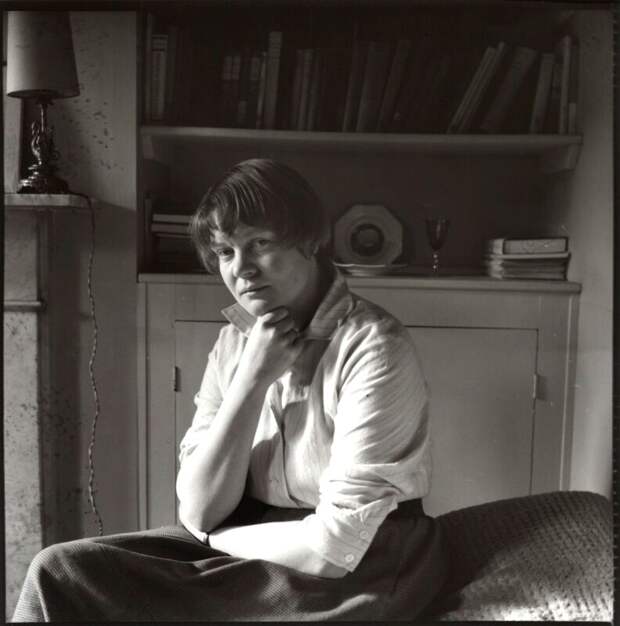

Iris Murdoch (July 15, 1919–February 8, 1999) — a rare philosopher with a poet’s pen, and one of the most incisive minds of the past century — explores the role of art as a force of resistance to tyranny and vehicle of cultural change in an arresting address she delivered to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in the spring of 1972, later included in the altogether revelatory posthumous collection Existentialists and Mystics: Writings on Philosophy and Literature (public library).

Two decades after the Soviet communist government forced Boris Pasternak to relinquish his Nobel Prize in Literature, Murdoch writes:

Tyrants always fear art because tyrants want to mystify while art tends to clarify.

The good artist is a vehicle of truth, he formulates ideas which would otherwise remain vague and focuses attention upon facts which can then no longer be ignored. The tyrant persecutes the artist by silencing him or by attempting to degrade or buy him. This has always been so.

In consonance with Baldwin’s assertion that “a society must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven,” Murdoch adds:

At regular intervals in history the artist has tended to be a revolutionary or at least an instrument of change in so far as he has tended to be a sensitive and independent thinker with a job that is a little outside established society.

In a sentiment that calls to mind the maelstrom of vicious opprobrium hurled at E.E. Cummings for his visionary defiance of tradition, which revolutionized literature, Murdoch considers how art often catalyzes ideological and cultural revolutions by first revolutionizing the art-form itself:

A motive for change in art has always been the artist’s own sense of truth. Artists constantly react against their tradition, finding it pompous and starchy and out of touch… Traditional art is seen as far too grand, and is then seen as a half-truth.

Murdoch counts among the “multifarious enemies of art” not only the deliberate assaults of political agendas and ideologies, but the half-conscious lacerations of our technology — that prosthetic extension of human intention, the unforeseen consequences and byproducts of which invariably eclipse its original intended uses. In a passage of sundering pertinence to our present political pseudo-reality, reinforced by the gorge of incessant newsfeeds, she writes:

A technological society, quite automatically and without any malign intent, upsets the artist by taking over and transforming the idea of craft,…

The post Salvation by Words: Iris Murdoch on Language as a Vehicle of Truth and Art as a Force of Resistance to Tyranny appeared first on FeedBox.