“Feeling, life, motion and emotion constitute its import,” philosopher Susanne Langer wrote of music, which she defined as “a highly articulated sensuous object.”

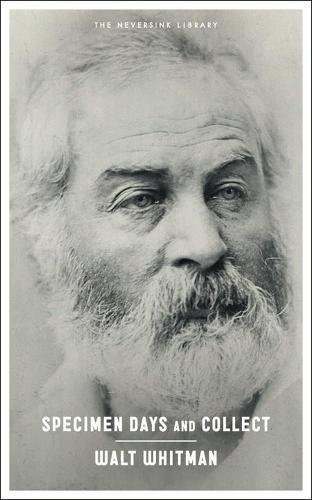

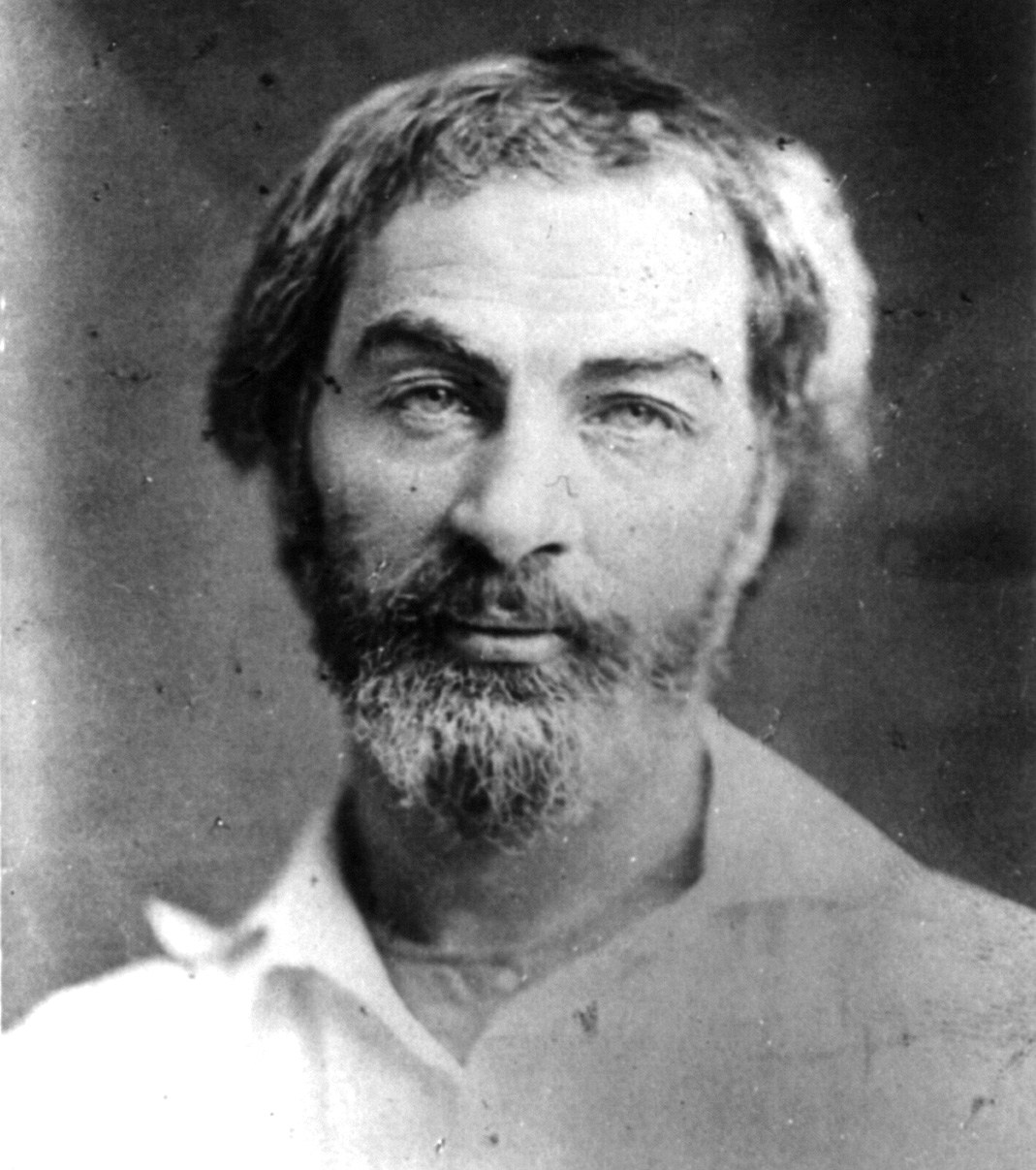

Although many great writers have contemplated the power of music, few have articulated it more perfectly or more sensuously than Walt Whitman (May 31, 1819–March 26, 1892) does in Specimen Days (public library) — the sublime collection of prose fragments and journal entries, which gave us Whitman on the wisdom of trees and which the poet himself described as “a melange of loafing, looking, hobbling, sitting, traveling — a little thinking thrown in for salt, but very little — …mostly the scenes everybody sees, but some of my own caprices, meditations, egotism.

” And what a beautiful, generous egotism it is.

One cold February evening in the last weeks of his sixtieth year, having finally recovered from the stroke that had rendered him paralyzed for two years, Whitman treated himself to a concert at Philadelphia’s opera house. Two decades after he wrote of music as “a god, yet completely human… supplying in certain wants and quarters what nothing else could supply,” Whitman found himself surrendering to its transcendent transport in a…

The post Walt Whitman on Beethoven and the Power of Music to Effect Full-Body Transcendence appeared first on FeedBox.