Author: Kathiann Kowalski / Source: Science News for Students

In a democracy, voters get to pick their leaders. And every vote should have the same weight in selecting the winner.

Indeed, under the U.S. Constitution, there is a general principal: One person, one vote. In some states, however, some votes may not carry the same weight.Here’s why.

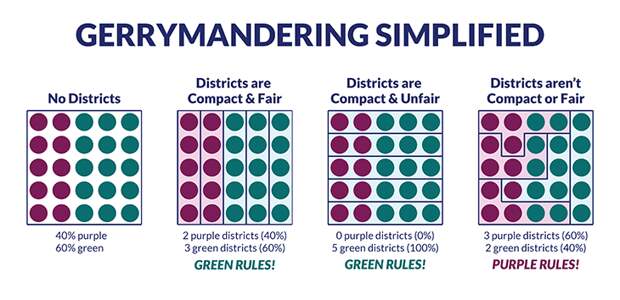

In the United States, many elected officials at the state and federal levels represent people in particular districts, or areas. In most cases, states decide the boundaries for those districts. But, sometimes, the people who draw those boundary lines may deliberately give a big advantage to one political party. This is called gerrymandering, and it’s not fair.

Last year, some voters in Wisconsin legally challenged what they claimed were gerrymandered districts. Another case in Maryland challenged changes to one district’s boundary lines. The cases went all the way to the Supreme Court. The high court has just handed down its decisions.

On June 18, the court ruled against the Wisconsin challengers. All nine justices found that individual voters could not challenge the whole state’s voting district map. But seven justices left open the possibility for individuals to challenge the lines of their individual districts.

On the same day, the court also ruled against the Maryland challengers. The challengers had wanted the lower court to prevent use of the old voting district map until the case was finished. But that’s a matter of discretion for the trial judge.

Both decisions essentially sidestepped the basic question: When, if ever, do districts drawn to favor one party over another violate the U.S. Constitution?

Moon Duchin is a mathematician at Tufts University in Medford, Mass. “Gerrymandering is basically a math problem,” she explains. “It’s asking how you can divide something up so the division has certain properties.” In this case, one group wants the boundaries of the voting districts to include more people from one political party or from a certain interest group. In this way, district voters will likely give a win to a selected party or group.

Choosing voters

Political parties in power want to stay in power. One way to do that is to encourage politicians in their party to support things their constituents want and need. Things like safety. Good schools. A clean environment. Good roads. Stable, well-paying jobs.

But sometimes political parties do more than that. They may redraw the boundaries of voting districts to make it much more likely that their supporters will win a majority. This is gerrymandering — the drawing of voting-district boundaries in such a way that one party gets a deliberate edge.

The practice goes back to at least 1812. That year, Massachusetts governor Elbridge Gerry’s team drew up a state voting map. One oddly shaped district looked like a fantasy monster. A Boston newspaper called it the “Gerry-mander.” And so the term was born.

Each state sets its districts for picking state and federal lawmakers. Districts should have roughly equal numbers of voters. In general, those voters should all live in the same neighborhoods or communities. Districts shouldn’t be drawn on the basis of factors such as race. (In fact, drawing districts in a way that dilutes the votes of racial minorities has been ruled unconstitutional. Doing it in a way that prevents minorities from electing their preferred candidate is also illegal.)

Wisconsin’s plan basically met those tests. Still, the plan gave a statewide edge to Republican candidates.

In 2012, for example, Republicans running for the state’s lawmaking branch got 48.6 percent of the popular vote statewide, or just under five in every 10 votes. Yet of 99 seats, Republicans won slightly more than six in every 10.

Like the original gerrymander, some voting districts may have odd — and tell-tale — shapes. But shape isn’t the only thing that matters. “You can do really unfair gerrymandering with shapes that look round and square and pretty,” Duchin notes. What’s more, oddly shaped districts might sometimes be fair.

“It’s not a beauty contest,” she says. Duchin and Mira Bernstein, also a mathematician at Tufts, wrote about the Wisconsin case and math in the October 2017 Notices of the American Mathematical Society.

Lawyers for both Maryland and Wisconsin did not want the courts to interfere. Maryland’s governor had even admitted that part of the reason for the challenged change was to give the Democrats an edge. Lawyers defending Wisconsin argued that voters could not challenge a statewide plan.

Story continues below image.

Cracking and packing

Math experts analyzed the Wisconsin state plan for the challengers. And those math experts found that two tricks led to gerrymandered vote results.

They refer to the first as “cracking.” It splits up a party’s supporters so they will be a minority in all or most districts. Their candidates might therefore lose in those places. The second trick is “packing.” It lumps a whole lot of one party’s backers into the same district. Now, their party’s candidate should win by a huge margin. However, many of the extra votes would be…

The post Supreme Court shies away from test on the math of voting rights appeared first on FeedBox.