Author: Sarah Zielinski / Source: Science News for Students

This is the eighth in a 10-part series about the ongoing global impacts of climate change. These stories will look at the current effects of a changing planet, what the emerging science suggests is behind those changes and what we all can do to adapt to them.

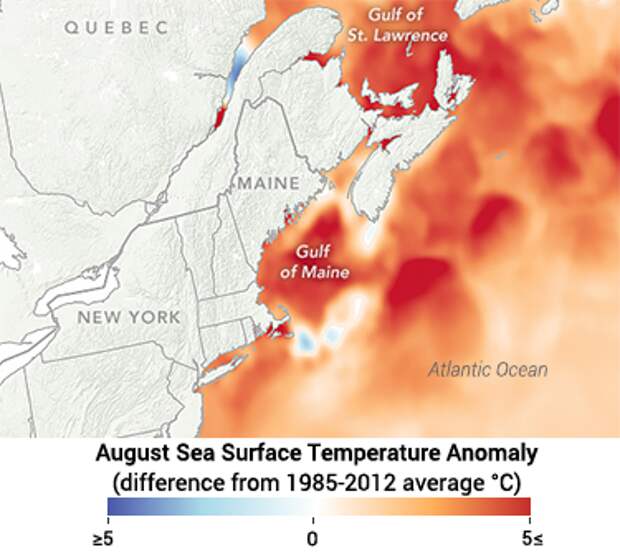

Last August, the Gulf of Maine experienced a heat wave. Average water temperatures at the surface reached the second-highest level ever recorded: 20.52° Celsius (68.93° Fahrenheit). That’s still a bit chilly for any person who might go for a dip. And it’s even colder diving beneath the surface. But for lobsters, these conditions are absolutely balmy — and they’re loving it. A few decades ago, the Gulf of Maine was at the northern extent of the American lobster’s range. Now, as waters have slowly warmed, it’s prime territory, and lobsters are booming.

This has been great news for Maine lobstermen, like Kristan Porter. He fishes out of Cutler, Maine, on his boat the Whitney & Ashley, named for his two daughters. “I’ve seen not-so-great lobstering when I first started, and, you know, [I’ve] had a pretty good run over the last 25 years or so.”

Back when Porter first started fishing on his own, in 1991, temperatures in the Gulf of Maine weren’t ideal for lobsters, says Andrew Pershing. He’s an oceanographer at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute in Portland.

But as climate change has warmed the planet — and its oceans — more and more, lobsters have migrated north. With rocky bottoms, kelp and other things that lobsters love, this is great lobster habitat, Pershing notes. Climate change has turned the gulf into a “paradise for lobsters,” he says.But it won’t stay that way. Pershing’s research shows that if people don’t cut back on emitting greenhouse gases, later this century the waters here will become as warm as those now found off New Jersey, way to the south. And that’s “not a place you associate with a really robust lobster fishery,” he adds.

Maine lobstermen like Porter are starting to worry. They know that these good times might not last forever. “If things go down,” Porter says, “it’s going to be hard on those coastal communities” that depend on lobsters. The lobster fishery in southern New England has already collapsed, in part due to climate change.

As the Atlantic warms, lobsters are chasing their preferred water temperature. They’re spreading into waters that were once too cold for them, and leaving those that are now too warm. This movement is not unusual. Many, many other plants and animals around the world, both on land and in the sea, are also on the move. As a result, old ecosystems — communities of species — are falling apart, and new ones are forming. Some species will be winners. Others will be losers. This is also true for the people that depend on these ecosystems. Some, like the Gulf of Maine lobstermen, will benefit from these changes, at least for a while. Many others will lose out.

Just how all this will turn out is still a bit of a mystery. Scientists can’t predict how everything in an ecosystem will change as climate warms and weather patterns change. “But I think we should be prepared for some complicated responses,” says Janneke Hille Ris Lambers. She’s an ecologist at the University of Washington in Seattle. “All these species interact in these complex direct and indirect ways.”

The fingerprint of climate change

Last August’s record-setting heat in Maine wasn’t that unusual. Worldwide, temperatures have been rising. 2018 was the fourth hottest year on record, exceeded only by 2016, 2015 and 2017. Since 1850, global temperatures have risen by about 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit), on average. Governments have agreed that they need to limit this rise to 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F). But to do so they will have to make big cuts to greenhouse gases — and soon.

“People think that one or two degrees doesn’t make a lot of difference,” says Gretta Pecl. She’s a marine ecologist in Australia, at the University of Tasmania in Hobart. But even humans notice such a small change. She notes that her family is happy to lounge in their hot tub at 36 °C (96.8 °F) but finds that they all get out when it cools to just 35 °C (95 °F).

“Every animal has a temperature range that it’s comfortable in,” notes Pershing. Humans and other warm-blooded creatures can adapt somewhat to changes in temperature. But in creatures like the lobster, body temperature is dependent on their environment. And local temperatures can affect many areas of their physiology (FIZZ-ee-OLL-oh-gee), such as how active an organism is and how fast it grows.

Where something lives depends on more than just temperature, though. A species needs the right habitat, including food and space to raise young. How much or little rain falls can matter, as can a huge number of other factors. So if one species moves north, not all of the other species in its ecosystem may find that new location to be a good home. Despite this, it is clear that species around the world are shifting where they live, Pecl says. It’s not everything. But overall, between 25 percent and 85 percent of species appear to be changing where they live. Those figures, she adds, are “surprisingly high. And the patterns are surprisingly consistent.”

The movement of all these species is “the fingerprint of climate change,” Pecl says, “but it’s a fuzzy fingerprint.” That’s because not everything is moving in the same way and at the same rate. Scientists are limited by their ability to detect all these changes. “But we are trying to make the best inferences we can,” she says.

Scientists can see that many species have changed their range. Depending on their hemisphere, they’ve been moving north or south, toward the poles. Species on land have moved an average of 17 kilometers (11 miles) per decade. Aquatic species are moving even faster, at an average of 72 kilometers (45 miles) per decade. Some terrestrial species have also moved up mountainsides, following their preferred temperatures. And a similar thing has happened in the seas, with some species moving to deeper, cooler zones.

Malin Pinsky is an ecologist at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. He and his colleagues have sought to look into the future. They’ve used computer models of future temperatures to see what might happen to ocean animals in North American waters throughout the next 80 years. The researchers focused on 686 species of sharks and other fish, crustaceans and cephalopods. Species would generally move north, they reported May 16, 2018 in PLOS ONE.

Some species, though, such as jack mackerel and canary rockfish, would move more than 1,000 kilometers (620 miles). In part, that’s because they can. They have the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea to the north. But species in the Gulf of Mexico can only move so far. “If animals move to the north, they’ll end up on land,” Pinsky notes. That means such species could go extinct from the Gulf.

A long commute

Worth some $1.5 billion, North American lobsters (Homarus americanus) are big business. In fact, this is “the most valuable fishery resource in North America,” notes Pershing’s team. That provides a lot of incentive to look into the fishery’s health — and its likely future in a changing climate.

In the United States, lobster can be found…

The post Warming pushes lobsters and other species to seek cooler homes appeared first on FeedBox.