Author: Kathiann Kowalski / Source: Science News for Students

More than three million people in Puerto Rico lost electricity in September 2017. Back-to-back hurricanes had just slammed into the island. Floods from Maria, the more powerful of them, knocked out many power plants.

Winds and mudslides toppled towers and the power lines they carried. Explains climate scientist Juan Declet-Barreto: “Losing power is not merely inconvenient. In a climate-ravaged, tropical area like Puerto Rico, it’s life-threatening.”With no electricity, hospitals had to delay surgeries. They couldn’t run many scans or tests, either. Without timely care, some patients died. Puerto Rico’s water-treatment plants lost power during Maria. As a result, people across the island lost access to clean water. And few people could cook or refrigerate food. Anyone lucky to have a portable stove or generator had to stand in long lines for fuel. Meanwhile, schools and businesses closed or cut their hours.

Declet-Barreto works for the Union of Concerned Scientists in Washington, D.C. But he grew up in Puerto Rico. His parents and sister’s family still live there. Phones went out shortly after Hurricane Maria made landfall. For days, Declet-Barreto didn’t know his family’s fate. Fortunately, they fared pretty well. And their electricity came back within a few weeks.

Many others were not as lucky. Four months after Maria, about one-third of the island still lacked electricity. Even after six months, roughly one in 10 people still couldn’t switch on the lights. It was nearly a year after Maria hit before everyone again had power.

Hurricanes are severe events, but Maria was especially bad. Its winds and flooding “couldn’t have been a more literal ‘perfect storm’ of conditions,” Declet-Barreto says. Its winds and fallen trees destroyed much of the island’s system for carrying electricity from power plants. Even before Maria, the company that delivers electricity had not been replacing aging equipment.

Puerto Rico is far from the only place that has struggled to keep its lights on, phones charged and computers powered up.

The electric grid is a term for the system that brings electricity from where it’s made to homes and businesses. Nearly everyone depends on that system. Yet as important as it is, this grid faces a host of threats. Some are simple and old. Others are complex and very new.

Fortunately, engineers are working on them. Their research aims to keep the grid going, despite natural — and some decidedly unnatural — disasters. Other projects are looking at how to get the lights back on more quickly after power outages. Still more work looks for ways to rely less on fossil fuels (mainly coal, oil and natural gas) and instead generate more electricity using cleaner wind and solar energy. The cleaner sources might not only help slow global warming, but also make the grid more resilient to shutdowns.

Bad weather, naughty squirrels and more

The grid has many thousands of pieces and parts. Power lines can stretch across continents. The grid’s electricity flows along many paths. Both its supply of energy and the public’s need for it can vary with the weather, time of day or day of the week.

Power engineers find it a challenge to keep such a complex system running smoothly. “We need to keep things perfectly balanced” says electrical engineer Chris Pilong. In other words, the electricity coming onto the grid at any time must match the amount being used. Pilong works at PJM Interconnection in Audubon, Penn. That company runs the grid for all or parts of 13 states plus Washington, D.C.

It doesn’t take much to throw the system out of whack. Too many people using too many air conditioners, computers, ovens and other appliances at the same time can disrupt the grid. Winds, falling trees and a build-up of ice can all bring down power lines. In fact, bad weather and other routine problems cause most U.S. power outages, a May 2018 report finds. It was authored by Grid Strategies. That’s an energy-analysis group based in Washington, D.C.

PJM and other grid operators know problems can and will arise. That’s why they often have power plants on standby. Those plants can power up if another plant goes down. However, catastrophic storms can overwhelm most backup plans, says Declet-Barreto. And climate change could worsen such events and make them more frequent.

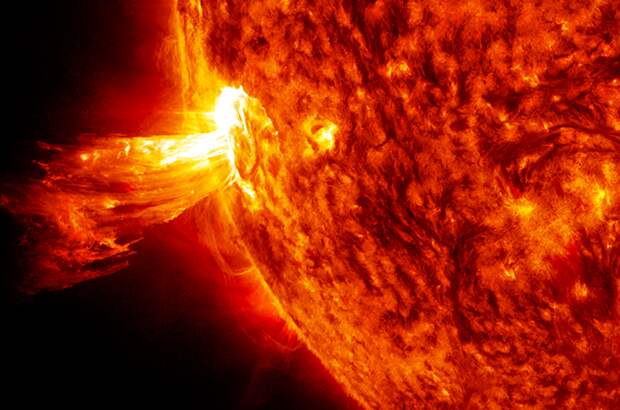

The sun can set off a different type of “weather” problem. Though rare, it can be severe. One 1989 power blackout in Quebec and the northeastern United States, for instance, was triggered by a coronal mass ejection. That’s a powerful burst of gas and magnetic energy from the sun. This stellar storm hurled electrically charged matter into space that messed with Earth’s magnetic field. This sent rogue electrical currents through parts of the grid.

Georgios Karagiannis is an environmental engineer who manages disaster risks. He works at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre in Ispra, Italy. Rogue currents from space aren’t an energy bonus for Earth-bound electricity users, he notes.

Far from it.

Those strong solar-flung electrical surges flow in one direction only, he explains. Yet the grid tends to transport current that changes direction many times per second. If space weather’s one-way surge of direct current enters that two-way alternating current grid, it can cause power outages. It also might harm costly equipment.

Then there are threats posed by terrorism. Bombs could destroy large power plants or transmission centers. Scarier still would be an electromagnetic pulse (EMP). It’s a huge burst of energy released by a nuclear blast high above Earth’s surface. If triggered in the right place, an EMP could knock out electricity across the United States and parts of Canada — perhaps for weeks or more. A 2017 report by the Electric Power Research Institute, based in Palo Alto,…

The post This grid moves energy, but not always reliably appeared first on FeedBox.