Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

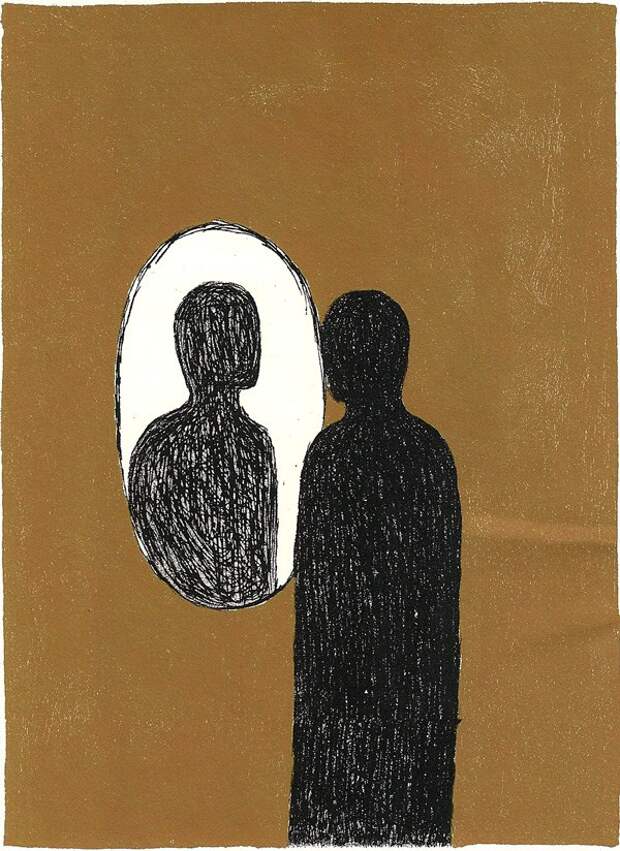

“There is, in sanest hours, a consciousness, a thought that rises, independent, lifted out from all else, calm, like the stars, shining eternal,” Walt Whitman wrote in contemplating identity and the paradox of the self. Whitman lived in an era before the birth of neuroscience, before psychology as we know it became a robust field of scientific study — before, that is, we began examining more closely whatever it is that we mean by the “self,” only to find that it doesn’t hold up to systematic scrutiny.

A century after Whitman, another great poet and great seer of the human experience articulated the terror and the beauty of this elemental fact: “The self is a style of being, continually expanding in a vital process of definition, affirmation, revision, and growth,” Robert Penn Warren wrote in admonishing against the trouble with “finding yourself,” “a process that is the image, we may say, of the life process of a healthy society itself.”Around the same time, a poet laureate of the life process — the great physician, etymologist, poet, and essayist Lewis Thomas (November 25, 1913–December 3, 1993) — explored the confounding nature of the self with uncommon insight and originality in the title essay of his altogether magnificent 1979 collection The Medusa and the Snail: More Notes of a Biology Watcher (public library).

Thomas writes:

We’ve never been so self-conscious about our selves as we seem to be these days. The popular magazines are filled with advice on things to do with a self: how to find it, identify it, nurture it, protect it, even, for special occasions, weekends, how to lose it transiently. There are instructive books, best sellers on self-realization, self-help, self-development.

Groups of self-respecting people pay large fees for three-day sessions together, learning self-awareness. Self-enlightenment can be taught in college electives.You’d think, to read about it, that we’d only just now discovered selves. Having long suspected that there was something alive in there, running the place, separate from everything else, absolutely individual and independent, we’ve celebrated by giving it a real name. My self.

In a testament to Ursula K. Le Guin’s conviction that “we can’t restructure our society without restructuring the English language,” Thomas traces the etymology of self, folded into which is just about the entire history of the human world:

The original root was se or seu, simply the pronoun of the third person, and most of the descendant words, except “self” itself, were constructed to allude to other, somehow connected people; “sibs” and “gossips,” relatives and close acquaintances, came from seu. Se was also used to indicate something outside or apart, hence words like “separate,” “secret,” and “segregate.” From an extended root swedh it moved into Greek as ethnos, meaning people of one’s own sort, and ethos, meaning the customs of such people. “Ethics” means the behavior of people like one’s self, one’s own ethnics.

Embedded in this evolutionary history of our language is something wholly uncorroborated by the evolutionary history of our biology — the misplaced hubris of exceptionalism. Thomas writes:

We tend to think of our selves as the only wholly unique creations in nature, but it is not so. Uniqueness is so commonplace a property of living things that there is really nothing at all unique about it. A phenomenon can’t be unique and universal at the same time. Even individual, free-swimming bacteria…

The post How a Jellyfish and a Sea Slug Illuminate the Mystery of the Self appeared first on FeedBox.