Author: Samantha Snively / Source: Atlas Obscura

“Observe when you walk abroad…and then your work will show the more naturally.” Recipe books don’t typically start this way. But for Hannah Woolley, cooking and science weren’t all that different.

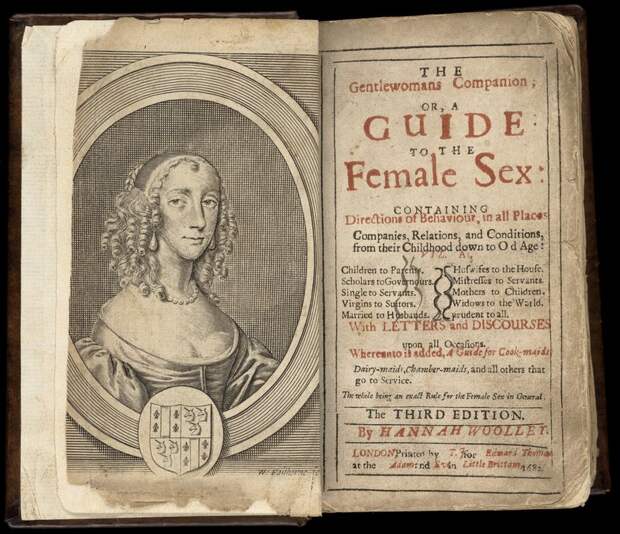

When Woolley published The Ladies Directory: Choice Experiments and Curiosities of Preserving in 1661, she became the first woman in England to release a household manual. Women of all classes craved these insights, and the little book of recipes, remedies, and etiquette quickly became a huge hit.

Woolley went on to publish four more books, and became the Martha Stewart of 17th-century England, making a living by selling her advice to the masses.In addition to cakes, roasted meat, and jellies, a number of recipes in Woolley’s books particularly encouraged women to create food that mimicked animals or natural phenomena. In one recipe for “Hedgehog Pudding,” for instance, Woolley advised cooks to use almond slivers and raisins to craft a hedgehog’s spines and eyes, respectively, in the sweet treat.

These recipes, which Woolley dubbed “New Experiments,” coincided with experimental science taking off across England. They also connected women’s work in the kitchen with the more formal experiments taking place in the Royal Society. This association of physicians, natural philosophers (a 17th-century term for “scientist”), and experimenters—all male, all upper-class—was founded in 1660. In order to fulfill its mission of “Improv[ing] Natural Knowledge,” the Royal Society spent its time looking through microscopes and conducting experiments examining the nature of air, colors, and perception.

Women’s scientific thoughts, and the experiments they headed in their kitchens, were of little interest to the men of the Royal Society.

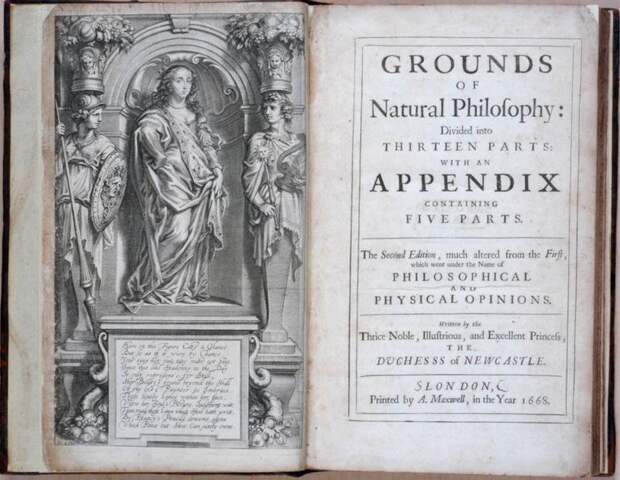

When writer and natural philosopher Margaret Cavendish visited the Royal Society in 1667, for example, men dismissed her as silly, despite her interest in observing “several fine experiments…of colours, loadstones, microscopes, and of liquors among others,” as Samuel Pepys, a member of Parliament, wrote in his diary. Cavendish’s “dress [was] so antick, and her deportment so ordinary, that I do not like her at all,” he continued, “Nor did I hear her say anything that was worth hearing, but that she was full of admiration.”

But in 17th-century English kitchens, women like Cavendish and Woolley observed and recreated the natural world in inventive ways. Upper- and lower-class ladies alike crafted elaborate dishes comprised of sugar-paste, marzipan, or jelly to look and act like animals, plants, or natural phenomena. These dishes, often unveiled as centerpieces at banquets or presents for friends and family, displayed not only a lady’s culinary skill, but also how she studied nature. The more closely a woman understood nature, the more lifelike her edible kitchen creations would be.

Some of these recipes were ubiquitous, such as the one for snow cream, which appears in many 17th-century handwritten recipe books. Elizabeth Godfrey’s recipe draws on the reader’s observation of snow in nature to know when the cream is ready: “when you see it look light like snow take it off with a skimmer,” she notes. In order to get the texture of snow cream right, a woman would have had to carefully observe what snow both looked and felt like. In order to replicate nature on the table…

The post How 17th-Century Women Replicated the Natural World on the Table appeared first on FeedBox.