Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

“A society must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven,” James Baldwin wrote in 1962 as he considered the creative process and the artist’s responsibility in society. “Tyrants always fear art because tyrants want to mystify while art tends to clarify,” Iris Murdoch insisted a decade later in celebrating literature as a vehicle of truth and art as a force of resistance.

That singular power of literary art to cast a clarifying light on society’s most perilous breaking points is what the novelist, essayist, biographer, and jazz scholar Albert Murray (May 12, 1916–August 18, 2013) explores in a portion of his superb 1973 book The Hero and the Blues (public library), which I discovered through a passing mention in theoretical cosmologist and saxophonist Stephon Alexander’s marvelous The Jazz of Physics.

Having lived through two World Wars, the Great Depression, and the cataclysmic dawn of the Civil Rights movement, Murray writes:

In truth, it is literature, in the primordial sense, which establishes the context for social and political action in the first place.

The writer who creates stories or narrates incidents which embody the essential nature of human existence in his time not only describes the circumstances of human actuality and the emotional texture of personal experience, but also suggests commitments and endeavors which he assumes will contribute most to man’s immediate welfare as well as to his ultimate fulfillment as a human being.It is the writer as artist, not the social or political engineer or even the philosopher, who first comes to realize when the time is out of joint. It is he who determines the extent and gravity of the current human predicament, who in effect discovers and describes the hidden elements of destruction, sounds the alarm, and even (in the process of defining “the villain”) designates the targets. It is the storyteller working on his own terms as mythmaker (and by implication, as value maker), who defines the conflict, identifies the hero (which is to say the good man — perhaps better, the adequate man), and decides the outcome; and in doing so he not only evokes the image of possibility, but also prefigures the contingencies of a happily balanced humanity and of the Great Good Place.

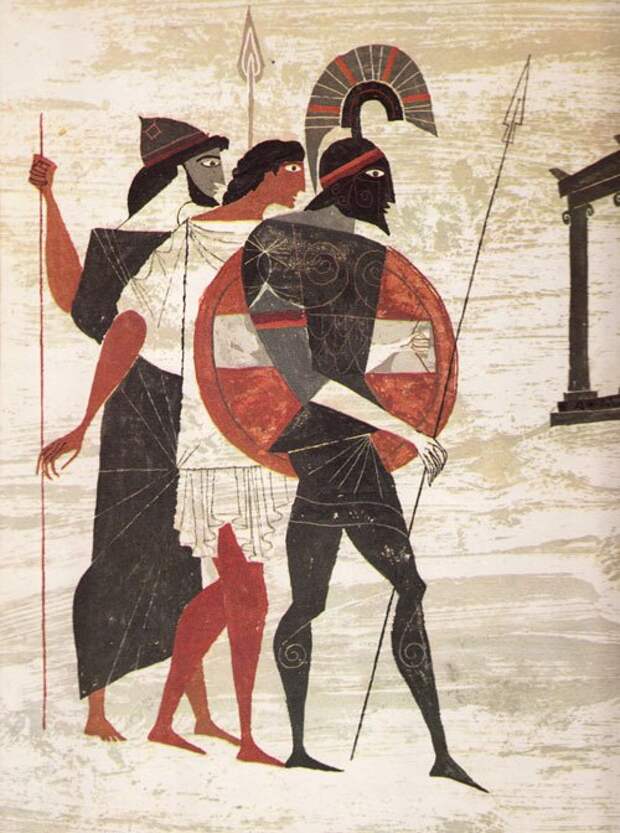

To examine the mechanics and ideals of cultural mythmaking is to inevitably consider what makes a hero.

Half a century after Joseph Campbell outlined his classic eleven stages of the hero’s journey, Murray locates the heart of heroism in what he terms antagonistic cooperation — the necessary tension between trial and triumph as the outside world antagonizes the hero…The post The Power of Antagonistic Cooperation: Albert Murray on Heroism and the Power of Storytelling to Redeem Our Broken Cultural Mythology appeared first on FeedBox.