Author: Tyler Berrigan / Source: Science News for Students

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.

Imagine a surface you never had to clean — because it never gets dirty. It stays spotless, resisting dirt and oil. New research finds that the secret to such a long-lasting, scrub-free shine might be microscopic pancakes.

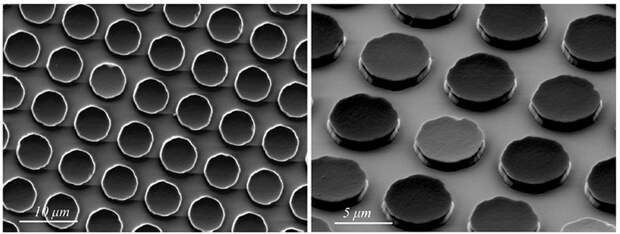

Some self-cleaning surfaces already exist. Stores don’t yet sell these self-cleaning clothes, kitchen utensils and windows, to name a few. But scientists are working on them. Up close, you’d see that microscopic pillars or columns cover the surface of many of these. A material coating those tiny structures repels oil and dirt. The narrow pillar tops also give grime less area to stick. That helps gunk slide off.

But micro-pillars are far from ideal. The tall, thin columns easily bend, snap and topple. Over time, dirt and oil can collect around damaged pillars. That buildup is hard to dislodge without some form of cleaning. And if the surface is glass, those busted pillars cause even more trouble. Bent and broken bits — and stuck gunk — interfere with light passing through the glass. That can blur or distort images viewed through them.

To address these issues, scientists in Norway took a new approach. Instead of pillars, they used shorter, squatter pancake shapes. And so far, those pancakes seem to do the trick.

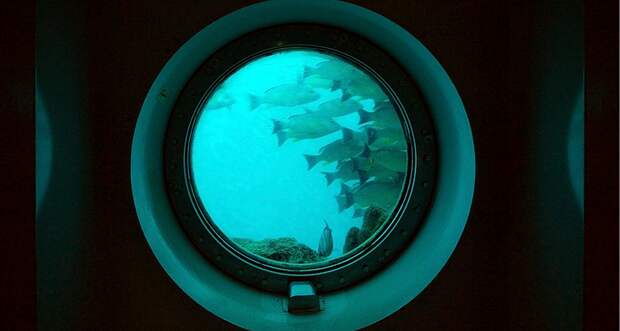

A window tested in the ocean has stayed clean and clear for more than a year.

“Unlike pillars, water moves freely between our pancake microstructures,” says Bodil Holst. She’s a physicist at the University of Bergen in Norway. With taller pillars, more water molecules get slowed down as they try to pass the structures. Water flows more easily around the shorter structures. Underwater, that liquid flow keeps dirt from sticking. In fact, that provides the self-cleaning, meaning the surface doesn’t need a dirt-repelling coating.

Their stout shape also makes the pancakes more durable. Imagine two pieces of chalk: one long and thin, the other short and flat, Holst says. “It would require a lot more effort to break a short piece of chalk,” she points out. “In the same way, it takes a lot more effort to break microscopic pancakes compared to pillars.”

In her team’s tests, those pancakes have remained firmly in place and in shape. Holst’s group described its findings December 12, 2018, in Nano Letters.

The pancake project arose from a real-world problem. “The company we work with uses light-detecting sensors to test water quality,” explains Naureen Akhtar. She is a physicist who works with Holst at the University of Bergen. “The problem is, the sensor sits behind a window that gets dirty far too quickly. Sometimes it’s soiled after…

The post A self-cleaning glass keeps itself spotless underwater appeared first on FeedBox.