Author: Tina Hesman Saey / Source: Science News

In Nevada, 40,000 people are stepping up to the cutting edge of precision medicine. They are getting their DNA deciphered by the testing company Helix.

The idea of the Healthy Nevada project is to link genetic and medical data with information about the environment to get a clearer picture of all the factors that influence health. The free tests are going like hot cakes.When the Healthy Nevada project launched a similar partnership with 23andMe in 2016, 5,000 residents were offered a free testing kit in exchange for participation in the program.

This feature launches a multipart series on consumer genetic testing. See the whole series.

“Within 24 hours, 5,000 people had broken our website and signed up really enthusiastically,” says project head Joseph Grzymski, a computational biologist at the Desert Research Institute’s Reno campus. Another 5,000 kits were offered up. “Within 24 hours that sold out,” Grzymski says, “and we had 4,000 people on a waiting list.”

Even without an invitation or a free deal, consumers are flocking to these tests. Last year, more than 7 million people, mostly in the United States, sent their DNA to testing companies, according to industry estimates.

“DNA testing is no longer a niche interest, it’s a mass consumer market, with millions of people wanting to experience the emotionally powerful, life-affirming discoveries that can come from simply spitting in a tube,” Howard Hochhauser, interim chief executive of the online geneaology testing company Ancestry, said in a public statement about the company’s 2017 holiday sales.

I am one of those 7 million who wanted a read on my DNA, to learn about myself and my heritage. And I went all out. My DNA is now part of the data banks of consumer genetic testing companies Ancestry, 23andMe, Family Tree DNA, Gencove, Genos, Helix, Living DNA and Veritas Genetics. (For a review of my experiences, click here). I learned some things about myself — and about the glaring limits of today’s consumer genetic tests.

Companies claim that they can read nearly everything about a person in his or her DNA profile. Some firms use DNA details to trace family trees or offer dietary advice and training regimens for burning fat or building muscle. Others go further out on a limb, claiming that testing a handful of genes can reveal a child’s future potential.

Estimated number of people since 2007 who have gotten consumer genetic testing

Estimated number who, in 2017 alone, got consumer genetic testing — more than all previous years combined

Need help choosing a wine? A test of variants in a few genes associated with taste and smell — along with a quick quiz — offers options that one company says will please your palate. There are even kits that claim to reveal superhero abilities, or that let two friends virtually mash up their DNA to see what their offspring might look like.

While some applications are clearly frivolous or pure entertainment, others are serious medical business. Consumers can buy tests that screen for gene variants that increase risk for developing cancer, high cholesterol, diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s. Human Longevity, in San Diego, pairs a readout of a person’s whole genome with extensive body imaging, blood tests and other medical screening to gauge a client’s health with the goal of increasing life span. Scientists say it’s probably going to take this sort of comprehensive information to really personalize medicine, but few people can afford Human Longevity’s $25,000 price tag.

These companies are part of a growing trend often called personalized, or precision, medicine. Health care systems, including national systems in Estonia, Finland, England and elsewhere, are adding DNA data to medical records, hoping to better tailor treatments to individual patients or even prevent illness. Consumer testing companies draw on databases compiled from such publicly funded research resources to make predictions about a customer’s health.

Some testing companies share their data with researchers who study human health and genetics, some do their own studies and some use the data as a revenue source, selling it to pharmaceutical companies. I opted to allow the companies to share my data with researchers. You don’t have to choose that option, but I like the idea of contributing to science.

And more research is needed. Scientists still haven’t really learned how to interpret the story in a person’s genetic instruction book, or genome, and apply it to an individual’s health care. Every researcher I talked to says that goal is far in the future.

A lot of what you can learn from consumer genetic testing is more useful for dinner party banter than health decisions. A few favorites:

Photic sneeze reflex — Some people sneeze when they suddenly encounter bright light. At least 54 genetic variants scattered among multiple chromosomes help control the sun-stoked achoo. Ear fold — How prominent the rim on the outer edge of the ear is depends in part on a variant of the EDAR gene. The gene is important for skin, ear, eye and hair development. Cilantro preference — Some people like cilantro, others say it tastes soapy. Studies have linked some genetic variants to liking or disliking the herb. Big toe or not? — Some people have longer second toes than big toes. At least 35 genetic variants, plus the balance of estrogen and testosterone in the womb, help determine toe (and finger) length. Sweet or salty — Preference for salty or sweet snacks is influenced by at least 43 genetic variants, some located in or near genes involved in brain development. Asparagus odor in urine — A variant near the OR2M7 gene influences whether people can smell asparagus in their urine after eating the vegetable. Smelling the roses — Some people can detect a specific rose scent chemical, thanks to an OR5A1 receptor gene variant.

“There will be a time when many more common health conditions will have tests you can do that will really inform you,” says Bryce Mendelsohn, a medical geneticist at the University of California, San Francisco. “But it will be years, years, decades before we’re really at that stage.”

In August, Mendelsohn opened the Preventive Genomics Clinic at UCSF’s Benioff Children’s Hospital. There, he counsels adults on what type of genetic testing is right for them, and what to expect from the results. He’s not against consumer genetic testing, but he tells his patients that it’s for entertainment purposes only.

“If they say, ‘I want to know about my ancestry. I want to know how much Neandertal I have,’ I say, ‘Great, that’s what consumer genetic testing is for.’ ”

But for medically relevant information — such as genetic variants that increase risk for cancer, high cholesterol or heart problems — Mendelsohn orders tests from labs that are certified to make thorough clinical diagnoses. And he makes sure his patients know what to expect and what their results mean.

“It’s not that companies that are selling tests are somehow evil,” Mendelsohn says; they just promise too much. “I just tell people up front, if you’re going to get this test, the odds are that you’re going to come back with nothing.”

False security

Daniel Cressman, a commercial real estate broker in San Francisco, wasn’t expecting to get any troubling or surprising results when he decided to have his DNA deciphered. He did it “just out of curiosity” after attending a conference on future trends. He wanted to be on the leading edge of what he sees as the wave of the future. One day soon, he predicts, “You’ll go to the doctor and the first thing they’ll do is pull up your genome.”

After hearing about the different levels of genetic testing that are offered (see “How much gets tested?”), Cressman decided he wanted the thorough approach: whole genome sequencing. To have his full genetic instruction book deciphered, rather than only certain parts, he looked into various companies’ offerings and ultimately settled on Veritas Genetics. The company will sequence a person’s genome for $999. Other companies offer whole genome sequencing, too, but for a higher price tag, anywhere from $1,295 for genealogy purposes to health testing ranging from $2,500 to more than $25,000.

Some of Cressman’s family and friends are not on board with genetic testing, he says. “Some people ask, ‘What if you discover something you don’t want to know?’ ” But Cressman thinks it’s usually better to know what’s potentially in store. “If I’m flying San Francisco to New York on an Airbus and there’s a crack in the wing, I’d kind of like to know before I get on the plane.” He didn’t discover any cracks in his genes that would cause him or his doctor concern. “Nothing popped out at all,” he says.

Like Cressman’s, my DNA’s story, based on Veritas’ whole genome sequencing, turned out to be pretty boring. For both of us, testing didn’t turn up any variations embedded in our DNA that are likely to cause us to develop a genetic disease. That’s good news, says clinical medical geneticist Gail Jarvik. “We tell people, ‘If you’re lucky, you have a boring genome. That’s what you really want.’ ”

But just because Veritas didn’t find anything scary in our genomes, doesn’t mean Cressman and I won’t develop health problems. Getting a clean bill of health based on your genes “can be very misleading and falsely reassuring,” says Jarvik, who heads the division of medical genetics at the University of Washington in Seattle. It can also be a bit of a letdown for people who expect revelations.

All DNA tests are not created equal. What you learn about your genetic makeup depends on the company you choose and the level of testing it does. Consumer tests fall into three main categories:

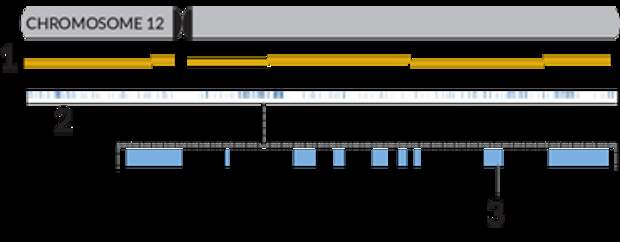

In theory, whole genome sequencing captures all of the 6 billion DNA bases in the genome. In reality, some regions are still a mystery (zooming in on the gold bars under chromosome 12 above would show testing gaps where the bars are staggered). Whole genome sequencing does not detect large chunks of missing, duplicated or rearranged DNA. Still, this approach, offered by Veritas Genetics and others, gives…

The post Consumer DNA testing promises more than it delivers appeared first on FeedBox.