Author: Liz Sanders / Source: Atlas Obscura

The sky was still dark when we arrived at the Bibal family’s ancestral home, a large farm house surrounded by pasture in Sainte-Gemme, France.

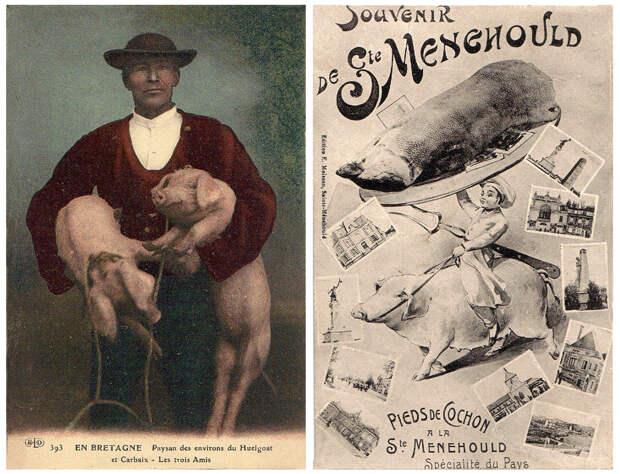

The day began—as it always does during their annual February visits—with a large family breakfast. We had visited the pig the evening before, when she was delivered by a local farmer. She slept on a thick bed of hay in a pen formerly used by the family patriarch, Fernand Bibal, to house animals. The large country house was equipped with all the accoutrements of subsistence farming: pens for livestock, chicken coops, and a granary. Normally, all that lies empty, except for once a year, when the large family convenes to keep the tradition of the tue-cochon alive.The wintertime custom, which literally translates to “pig slaughter,” was once a matter of survival. When food was scarce and snow covered fields and gardens, families needed preserved foods. In France, pork provided the necessary base for rural families’ meals, and the process of salting and drying pork remained crucial for survival until only a few generations ago. Pork achieved such high regard that pigs were featured in famous French Belle Epoque postcards, and quintessential foods such as confit, pâté, boudin, and all manner of sausages can be traced to this need to preserve meat before the advent of refrigeration.

The Bibals no longer live in the country. Like many families, they left the fields for office jobs and city life: Frédéric practices law, Cécile is a physician, and they live just outside Paris with their four children, Noé, Joseph, Madeleine, and Suzanne. But each year, the Bibals’ extended family convenes to continue the tue-cochon tradition.

“We [still] do it because in our family, we have always done it,” says Marc Bibal, Frédéric’s brother. “In our region, everyone did it. There is not a family that has not participated in the tue-cochon.”

Families like the Bibals have another motivation for keeping up the tradition. While many French regions have historically participated in the tue-cochon, their recipes, which families hand down, are distinguished by local tastes and how preservation requirements differ by climate. “The sausage we love can’t be found easily. Or if we find it, it’s now too expensive to buy in stores,” says Marc. “We’ve been eating it this way for so long, we want to keep eating it.”

What sets the Bibal family apart is that their great-grandfather, Fernand, was himself a Saigneur, a respected post occupied by…

The post This French Family Wants Their Kids to Know How the Sausage Is Made appeared first on FeedBox.