“A society must assume that it is stable,” James Baldwin wrote in his timeless treatise on the creative process, “but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven.” And yet, paradoxically, in the very act of exposing the abiding instability of existence, art moors us to a sense of the eternal and becalms our momentary tumults against the raging ocean that has always washed, and will always wash, the shoreline of the human spirit.

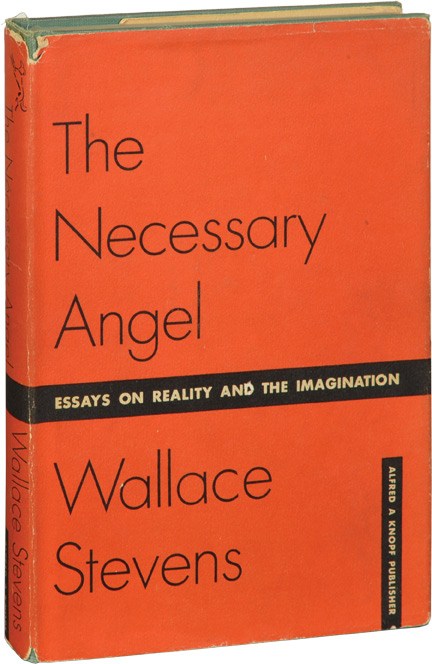

The poet Robert Penn Warren captured this beautifully in his meditation on the vital role of art in a thriving democracy, in which he asserted that art “is the process by which, in imagining itself and the relation of individuals to one another and to it, a society comes to understand itself, and by understanding, discover its possibilities of growth.”A generation earlier, Wallace Stevens (October 2, 1879–August 2, 1955), another Pulitzer-winning poet, examined a complementary aspect of the relationship between culture and creativity in his astonishingly timely 1951 book The Necessary Angel: Essays on Reality and the Imagination (public library), titled after a line from one of Stevens’s most beloved poems: “I am the necessary angel of earth, / Since, in my sight, you see the earth again, / Cleared of its set and stubborn, man-locked set…”

Stevens controverts the notion that the imagination is a counterpoint to reality and instead insists that the two are in essential interplay:

The imagination loses vitality as it ceases to adhere to what is real… There are degrees of the imagination, as, for example, degrees of vitality and, therefore, of intensity. It is an implication that there are degrees of reality.

He points to nobility as a defining characteristic of the imagination — the means by which the creative spirit protects its interior integrity from what he calls “the pressure of reality,” a pressure of immense and almost unbearable intensity today. In a passage of astounding prescience, Stevens writes a decade after the end of of WWII and more than half a century before the present tyranny of the 24/7 news cycle:

By the pressure of reality, I mean the pressure of an external event or events on the consciousness to the exclusion of any power of contemplation.

[…]For more than ten years now, there has been an extraordinary pressure of news — let us say, news incomparably more pretentious than any description of it, news, at first, of the collapse of our system, or, call it, of life; then of news of a new world, but of a new world so uncertain that one did not know anything whatever of its nature, and does not know now, and could not tell whether it was to be all-English, all-German, all-Russian, all-Japanese, or all-American, and cannot tell now; and finally news of a war, which was a renewal of what, if it was not the greatest war, became such by this continuation. And for more than ten years, the consciousness of the world has concentrated on events which have made the ordinary movement of life seem to be the movement of people in the intervals of a storm. The disclosures of the impermanence of the past suggested, and suggest, an impermanence of the future. Little of what we have believed has been true… It is a question of pressure, and pressure is incalculable and eludes the historian. The Napoleonic era is regarded as having had little or no effect on the poets and the novelists who lived in it. But Coleridge and Wordsworth and Sir Walter Scott and Jane Austen did not have to put up with Napoleon and Marx and Europe, Asia and Africa all at one time. It seems possible to say that they knew of the events of their day much as we know of the bombings in the interior of China and not at all as we know of the bombings of London, or, rather, as we should know of the bombings of Toronto or Montreal.

With an eye to the disorientation of the transitional era in which he is writing — an era perhaps as transitional and disorienting as our own — Stevens examines the familiar helplessness of witnessing reality crumble:

Rightly or wrongly, we feel that the fate of a society is involved in the orderly disorders of the present time. We are confronting, therefore, a set of events, not only beyond our power to tranquillize them in the mind, beyond our power to reduce them and metamorphose them, but events that stir the emotions to violence, that engage us in what is direct and immediate and real, and events that involve the concepts and sanctions that are the order of our lives and may involve our very lives; and these events are occurring persistently with increasing omen, in what may be called our presence. These are the things that I had in mind when I spoke of the pressure of reality, a pressure great enough and prolonged enough to bring about the end of one era in the history of the imagination and, if so, then great enough to bring about the beginning of another.

The imagination, Stevens argues, is our mightiest survival mechanism in such tumultuous times — those endowed with…

The post Wallace Stevens on Reality, Creativity, and Our Greatest Self-Protection from the Pressure of the News appeared first on FeedBox.