Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

“Time and reason are functions of each other,” Ursula K. Le Guin wrote in her philosophical novel exploring why honoring the continuity of past and future is the wellspring of moral action. The human animal is indeed a temporal creature, our experience of time at the center of our psychology. Locating ourselves is therefore largely a matter of locating ourselves in the stream of time — diurnal, civilizational, and cosmic.

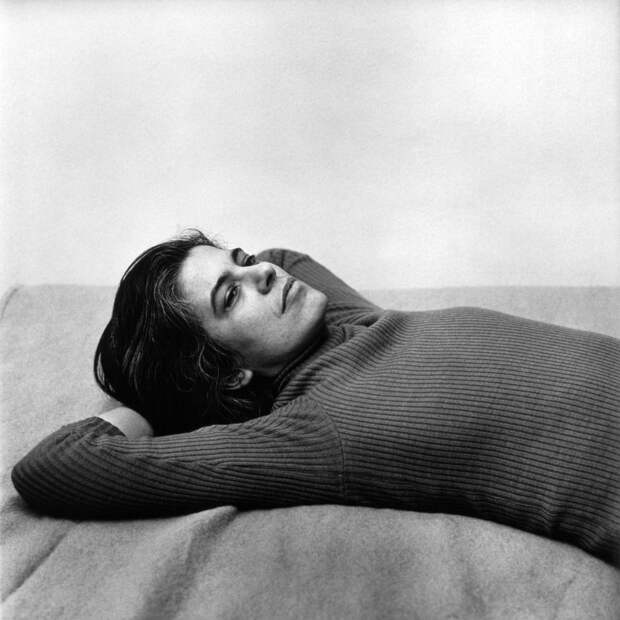

It is hard enough to grapple with the micro end of the spectrum — to acknowledge, with Annie Dillard, that “how we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives” — and nearly impossible to fathom the macro, the incomprehensible scales of spacetime. And yet most of our suffering seems to reside in the middle of the spectrum — in our understanding of and orientation toward the selective collective memory we call history. In Figuring, I wrote that history is not what happened, but what survives the shipwrecks of judgment and chance. Whose judgment? one inevitably asks, and how much room for choice in a universe governed by chance — by randomness and chaos? What, then, do we make of history, and what does it make of us?That is what Susan Sontag (January 16, 1933–December 28, 2004) explores in a 1967 essay about the work of the Romanian philosopher and essayist Emil Cioran, found in Styles of Radical Will (public library) — the indispensable volume that gave us Sontag on art as a form of spirituality and the paradoxical role of silence in creative culture.

Sontag writes:

We understand something by locating it in a multi-determined temporal continuum. Existence is no more than the precarious attainment of relevance in an intensely mobile flux of past, present, and future. But even the most relevant events carry within them the form of their obsolescence. Thus, a single work is eventually a contribution to a body of work; the details of a life form part of a life history; an individual life history appears unintelligible apart from social, economic, and cultural history; and the life of a society is the sum of “preceding conditions.” Meaning drowns in a stream of becoming: the senseless and overdocumented rhythm of advent and supersession. The becoming of man is the history of the exhaustion of his possibilities.

Half a century before Rebecca Solnit — a Sontag of our own time — insisted that we must know our history in order to rewrite its broken stories, that “you need to know the patterns to see how people are fitting the jumble of facts into what they already have: selecting, misreading, distorting, excluding, embroidering, distributing empathy here but not there, remembering this echo or forgetting…

The post Becoming a Being: Susan Sontag on Transcending the Bounds and Biases of History appeared first on FeedBox.