Author: Elliot Williams / Source: Hackaday

It all started when I bought a late-1990s synthesizer that needed a firmware upgrade. One could simply pull the ROM chip, ship it off to Yamaha for a free replacement, and swap in the new one — in 2003. Lacking a time machine, a sensible option is to buy a pre-programmed aftermarket EPROM on eBay for $10, and if you just want a single pre-flashed EPROM that’s probably the right way to go.

But I wanted an adventure.Spoiler alert: I did manage to flash a few EPROMs and the RM1X is happily running OS 1.13 and pumping out the jams. That’s not the adventure. The adventure is trying to erase UV-erasable EPROMS.

And that’s how I ended up with a small cardboard fire and a scorched tanning lamp, and why I bought a $5 LED, and why I left EPROMs out in the sun for four days. And why, in the end, I gave up and ordered a $15 EPROM eraser from China. Along the way, I learned a ton about old-school UV-erasable EPROMs, and now I have a stack of obsolete silicon that’s looking for a new project like a hammer looks for a nail — just as soon as that UV eraser arrives in the mail.

Flash from the Past: UV EPROMs

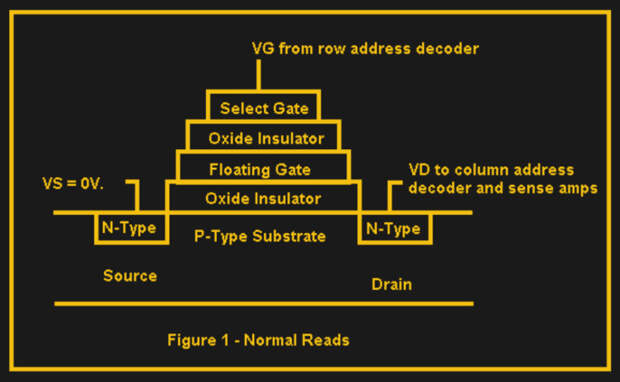

Old-school EPROMs are made by laying out a bunch of field-effect transistors (FETs) in an IC. In read mode, a gate voltage is applied to each transistor, and whether it conducts or not determines if the bit of data stored there is a one or a zero. The gimmick is that an additional metal layer — the floating gate — is interposed between the FET’s channel and the gate. Putting a negative charge on this floating middle layer will raise the voltage required to turn the transistor on from the outside.

A bit of info can thus be stored in the physical form of excess electrons on the floating gate.

In a UV EPROM, the floating gate is insulated all around by an oxide layer, so it retains this negative charge essentially indefinitely. You get extra electrons onto the floating gate through “hot-electron injection”: applying enough voltage across the floating gate that electrons jump through the insulating layer. When reading the data, transistors that have a negatively charged gate won’t conduct at their normal gate voltage, while those that haven’t been programmed will. Easy peasy.

But then how do you get rid of the excess floating-gate electrons in order to blank an EPROM? The original method proposed to erase ceramic-encased EPROMs was to use X-rays in a 600° C oven, but cooler heads prevailed and chipmakers instead installed a relatively expensive crystal window that’s UV permeable, allowing longer wavelengths of carcinogenic light to coax the electrons back into the substrate. Apparently, in the 1970’s hard-UV lamps were commonly used for their germicidal effects in barbershops and the like, so having a UV-erasable EPROM was convenient. My own attempts to clear UV EPROMs have been anything but.

How Not To Clear an EPROM

I ordered a ten-pack of used (!) 27C160 UV EPROMs online and was a bit surprised when only three of the ten arrived with the memory cleared. Unless I could figure out how to blank a UV EPROM, I would only have three chances to flash my synth’s EPROM. And since I had a ROM dump with 16-bit words of unknown endianness, there was a 50% chance that I’d need to try twice. This left me with only one EPROM to use in developing an EPROM programmer. So I decided to see if I could erase them to provide myself with a safety net.

I have read, in these very pages, tales of success erasing UV EPROMs with a UV LED and by harnessing the power of the sun. My EPROM’s datasheet specifies “wavelengths shorter than 400 nm” and recommends “30 to 40 minutes using an UV lamp with 12 mW / cm2 power rating.” It also suggests that approximately one week of exposure to direct sunlight would suffice. So these Hackaday stories sound plausible on the surface.

Maybe November sunlight in southern Germany doesn’t pack the same UV punch of full summer in southern California or wherever the datasheet was written, but the two chips that I left out on our balcony displayed exactly the same data after a week of exposure as they did beforehand. Not a single bit flipped, and there were four fully sunny days. Maybe it was the cold? I asked around Hackaday HQ, and Jenny said she’d tried once and it took three weeks or more over an English summer. This was clearly not the quick way to go.

So I tried a random UV LED from my junkbox, and got nothing. True UV LEDs are difficult and expensive to make, and this one was very visibly blue. So while it was failing to erase an EPROM on…

The post Fail of the Week: EPROMs, Rats’ Nests, Tanning Lamps, and Cardboard on Fire appeared first on FeedBox.