Author: Roberta Kwok / Source: Science News for Students

In 2009, biologist Dan Lahr received an intriguing email from another researcher.

It included a photo of a strange organism. The researcher had discovered the microbe in a floodplain in central Brazil. Its yellowish-brown shell had a distinctive, triangle-like shape.The shape reminded Lahr of the wizard’s hat in The Lord of the Rings movies. “That’s Gandalf’s hat,” he remembers thinking.

Lahr is a biologist at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. He realized the one-celled life form was a new species of amoeba (Uh-MEE-buh). Some amoebas have a shell, as this one did. They may build those shells out of molecules they make themselves, such as proteins. Others may use bits of material from their environment, such as minerals and plants. Still other amoebas are “naked,” lacking any shell. To learn more about the newfound amoeba, Lahr would need more specimens.

Two years later, another Brazilian scientist sent him pictures of the same species from a river. But the bonanza came in 2015. That’s when a third scientist emailed him. This researcher, Jordana Féres, had collected a few hundred of the triangular amoebas. It was enough for her and Lahr to begin a detailed study of the species.

They examined the microbes under a microscope. The amoeba, they found, built its hat-shaped shell from proteins and sugars that it made. The big question is why the microbe needs that shell. Perhaps it offers protection from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays. Lahr named the species Arcella gandalfi (Ahr-SELL-uh Gan-DAHL-fee).

Lahr suspects many more amoeba species await discovery. “People are just not looking [for them],” he says.

Scientists still know little about amoebas. Most biologists study organisms that are either simpler or more complex. Microbiologists, for instance, often focus on bacteria and viruses. Those microbes have simpler structures and can cause disease. Zoologists prefer to study larger, more familiar animals, such as mammals and reptiles.

Amoebas have largely “been ignored,” notes Richard Payne. He is an environmental scientist at the University of York in England. “They’ve been sort of caught in the middle for a long time.”

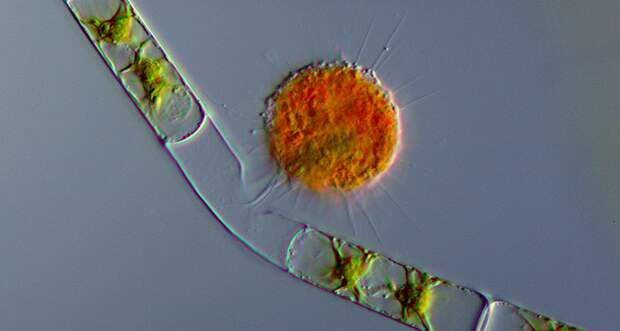

But when scientists do peer at these odd little organisms, they find big surprises. Amoebas’ foods range from algae to brains. Some amoebas carry bacteria that protect them from harm. Others “farm” the bacteria they like to eat. And still others may play a role in Earth’s changing climate.

What’s on the menu? Fungi, worms, brains

Though you can’t see them, amoebas are everywhere. They live in soil, ponds, lakes, forests and rivers. If you scoop up a handful of dirt in the woods, it will probably contain hundreds of thousands of amoebas.

But those amoebas may not all be closely related to one another. The word “amoeba” describes a wide variety of single-celled organisms that look and behave a certain way. Some organisms are amoebas for only part of their lives. They can switch back and forth between an amoeba form and some other form.

Like bacteria, amoebas have just one cell. But there the similarity ends. For one thing, amoebas are eukaryotic (Yoo-kair-ee-AH-tik). That means their DNA is packed inside a structure called a nucleus (NEW-klee-uhs). Bacteria have no nucleus. In some ways, amoebas are more similar to human cells than to bacteria.

Also unlike bacteria, which hold their shape, shell-free amoebas look like blobs. Their structure changes a lot, Lahr says. He calls them “shape-shifters.”

Their blobbiness can come in handy. Amoebas move using bulging parts called pseudopodia (Soo-doh-POH-dee-uh). The term means “false feet.” These are extensions of the cell’s membrane. An amoeba can reach out and grab some surface with a pseudopod, using it to crawl forward.

Pseudopodia also help amoebas eat. A stretched-out pseudopod can engulf an amoeba’s prey. That allows this microbe to swallow bacteria, fungal cells, algae — even small worms.

Some amoebas eat human cells, causing sickness. In general, amoebas don’t cause as many human diseases as bacteria and viruses do. Still, some species can be lethal. For example, a species known as Entamoeba histolytica (Ehn-tuh-MEE-buh Hiss-toh-LIH-tih-kuh) can infect human intestines. Once there, “they literally eat you,” Lahr says. The disease they cause kills tens of thousands of people each year, mostly in areas that lack clean water or sewer systems.

The most bizarre illness caused by an amoeba involves the species Naegleria fowleri (Nay-GLEER-ee-uh FOW-luh-ree). Its nickname is the “brain-eating amoeba.” Very rarely, it infects people who swim in lakes or rivers. Once inside the nose, it can travel to the brain where it feasts on brain cells. This infection is usually deadly. The good news: Scientists know of only 34 U.S. residents who became infected between 2008 and 2017.

A tiny can opener

A scientist named Sebastian Hess recently discovered the tricks some amoebas use to eat. He studies eukaryotic microbes in Canada at Dalhousie University. That’s in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Hess has loved watching tiny critters through a microscope since he was a kid.

Ten years ago, Hess punched through the ice of a frozen pond in Germany. He collected a sample of water and took it back to…

The post Amoebas are crafty, shape-shifting engineers appeared first on FeedBox.