Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

“Everybody should be quiet near a little stream and listen,” the great children’s book author Ruth Krauss — a philosopher, really — wrote in her last and loveliest collaboration with the young Maurice Sendak in 1960. At the time of her first collaboration with Sendak twelve years earlier, just after the word “workaholic” was coined, the German philosopher Josef Pieper was composing Leisure, the Basis of Culture — his timeless and increasingly timely manifesto for reclaiming our human dignity in a culture of busyness.

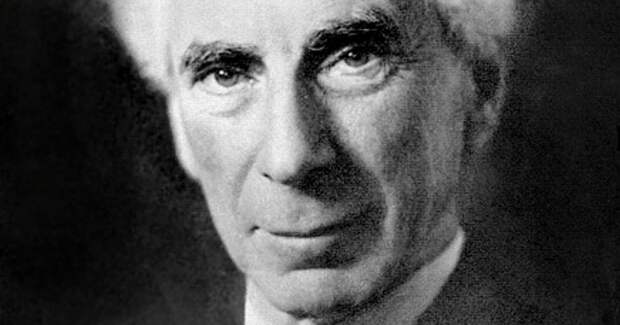

“Leisure,” Pieper wrote, “is not the same as the absence of activity… or even as an inner quiet. It is rather like the stillness in the conversation of lovers, which is fed by their oneness.”A generation earlier, with a seer’s capacity to peer past the horizon of the present condition and anticipate a sweeping cultural current before it has flooded in, and with a sage’s ability to provide the psychic buoy for surviving the current’s perilous rapids, Bertrand Russell (May 18, 1872–February 2, 1970) addressed the looming cult of workaholism in a prescient 1932 essay titled In Praise of Idleness (public library).

Russell writes:

A great deal of harm is being done in the modern world by belief in the virtuousness of work, and that the road to happiness and prosperity lies in an organized diminution of work.

With his characteristic wisdom punctuated by wry wit, he examines what work actually means:

Work is of two kinds: first, altering the position of matter at or near the earth’s surface relatively to other such matter; second, telling other people to do so. The first kind is unpleasant and ill paid; the second is pleasant and highly paid. The second kind is capable of indefinite extension: there are not only those who give orders, but those who give advice as to what orders should be given.

Usually two opposite kinds of advice are given simultaneously by two organized bodies of men; this is called politics. The skill required for this kind of work is not knowledge of the subjects as to which advice is given, but knowledge of the art of persuasive speaking and writing, i.e., of advertising.

Russell points to landowners as a historical example of a class whose idleness was only made possible by the toil of others. For the vast majority of our species’ history, up until the Industrial Revolution, the average person spent nearly every waking hour working hard to earn the basic necessities of survival. Any marginal surplus, he notes, was swiftly appropriated by those in power — the warriors, the monarchs, the priests. Since the Industrial Revolution, other power systems — from big business to dictatorships — have simply supplanted the warriors, monarchs, and priests. Russell considers how the exploitive legacy of pre-industrial society has corrupted the modern social fabric and warped our value system:

A system which lasted so long and ended so recently has naturally left a profound impress upon men’s thoughts and opinions. Much that we take for granted about the desirability of work is derived from this system, and, being pre-industrial, is not adapted to the modern world. Modern technique has made it possible for leisure, within limits, to be not the prerogative of small privileged classes, but a right evenly distributed throughout the community. The morality of work is the morality of slaves, and the modern world has no need of slavery.

Writing nearly a century after Kierkegaard extolled the existential boon of idleness, Russell considers how this manipulated mentality has hypnotized us into worshiping work as virtue and scorning leisure as laziness, as weakness, as folly, rather than recognizing it as the raw material of social justice and the locus of our power:

The conception of duty, speaking historically, has been a means used by the holders of power to induce others to live for the interests of their masters rather than for their own. Of course the holders of power conceal this fact from themselves by managing to believe that their interests are identical with the larger interests of humanity. Sometimes this is true; Athenian slave owners, for instance, employed part of their leisure in making a permanent contribution to civilization which would have been impossible under a just economic system. Leisure is essential to civilization, and in former times leisure for the few was only rendered possible by the labors of the many. But their labors were valuable, not because work is good, but because leisure is good. And with modern technique it would be possible to distribute leisure justly without injury to civilization.

Russell notes that WWI — which was dubbed “the war to end all wars” by a world willfully blind to the fact that violence begets more violence, unwitting that this world war would pave the way for the next — furthered our civilization conflation of duty with work and work with virtue, lulling us into the modern trance of busyness. More than half a century before Annie Dillard observed that “how we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives,” Russell traces the ledger of our existential spending back to war’s false promise of freedom:

The war showed conclusively that, by the scientific organization of production, it is possible to keep modern populations in fair comfort on a small part of the working capacity of the modern world. If, at the end of the war, the scientific organization, which had been created in order to liberate men for fighting and munition work, had been preserved, and the hours of work had been cut down to four, all would have been well. Instead of that the old chaos was restored, those whose work was demanded were made to work long hours, and the rest were left to starve as unemployed. Why? Because work is a duty, and a man should not receive wages in proportion to what he has produced, but in proportion to his virtue as exemplified by his industry.

Pointing out that this equivalence originates in the same morality — or, rather, immorality — that produced the slave state, he exposes the core cultural falsehood it has effected, which stands as a monumental obstruction to equality and social justice in contemporary society:

The idea that the poor should have leisure has always been shocking to the rich.

Born in an era when urban workingmen had just acquired the right to vote in Great Britain, Russell draws on his own childhood for a stark illustration of this belief and its far-reaching tentacles of socioeconomic oppression:

I remember hearing an old Duchess say: “What do the poor want with holidays? They ought to work.” People nowadays are less frank, but the sentiment persists, and is the source of much of our economic confusion.

That sentiment, Russell reminds us again and again, is ahistorical. Advances in science, technology, and the very mechanics of society have made it no longer necessary for the average person to endure fifteen-hour workdays in order to obtain basic sustenance, as adults — and often children — had to in the early nineteenth century. But while the allocation of our time in relation to need has changed immensely, our attitudes about how that time is spent hardly have. He writes:

Every human being, of necessity, consumes, in the course of his life, a certain amount of the produce of human…

The post In Praise of Idleness: Bertrand Russell on the Relationship Between Leisure and Social Justice appeared first on FeedBox.