Author: Anne Ewbank / Source: Atlas Obscura

In 1877, Japan’s Meiji Emperor watched his aunt, the princess Kazu, die of a common malady: kakke. If her condition was typical, her legs would have swollen, and her speech slowed. Numbness and paralysis might have come next, along with twitching and vomiting.

Death often resulted from heart failure.The emperor had suffered from this same ailment, on-and-off, his whole life. In response, he poured money into research on the illness. It was a matter of survival: for the emperor, his family, and Japan’s ruling class. While most diseases ravage the poor and vulnerable, kakke afflicted the wealthy and powerful, especially city dwellers. This curious fact gave kakke its other name: Edo wazurai, the affliction of Edo (Edo being the old name for Tokyo). But for centuries, the culprit of kakke went unnoticed: fine, polished, white rice.

Gleaming white rice was a status symbol—it was expensive and laborious to husk, hull, polish, and wash. In Japan, the poor ate brown rice, or other carbohydrates such as sweet potatoes or barley. The rich ate polished white rice, often to the exclusion of other foods.

This was a problem. Removing the outer layers of a grain of rice also removes one vital nutrient: thiamine, or vitamin B-1. Without thiamine, animals and humans develop kakke, now known in English as beriberi. But for too long, the cause of the condition remained unknown.

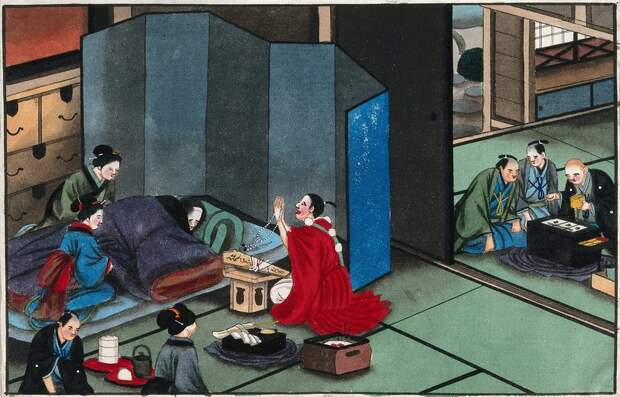

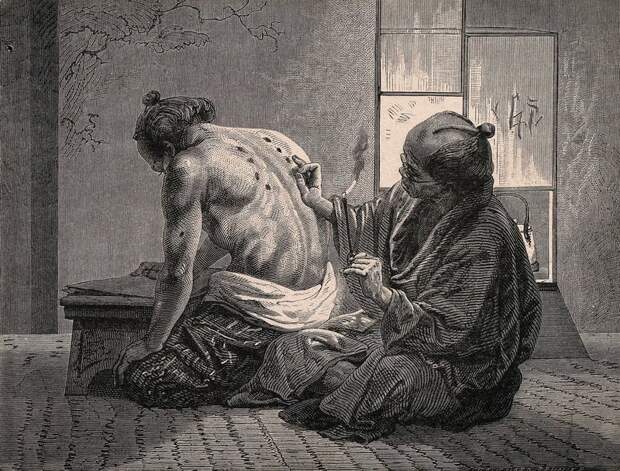

In his book Beriberi in Modern Japan: The Making of a National Disease, Alexander R. Bay describes the efforts of Edo-era doctors to figure out the disease. A common suspect was dampness and damp ground. One doctor administered herbal medicines and a fasting regimen to a samurai, who died within months. Other doctors burned dried mugwort on patients’ bodies to stimulate qi and blood flow.

Some remedies did work—even if they didn’t come from a true understanding of the disease. Katsuki Gyuzan, an early, 18th-century doctor, believed Edo itself was the issue. Samurai, he wrote, would come to Edo and get kakke from the water and soil. Only samurai who went back to their provincial homes—going over the Hakone Pass—would be cured. Those who were seriously ill had to move quickly, “for the worst cases always result in death,” Katsuki cautioned. Since heavily processed white rice was less available outside Edo and in the countryside, this likely was a cure. Similarly, a number of physicians prescribed barley and red beans, which both contain thiamine.

By 1877, Japan’s beriberi problem was getting really serious. When the princess Kazu died of kakke at 31, it was only a decade after her former husband, Japan’s shogun, had died, almost certainly from the mysterious disease. Machine-milling made polished rice available to the masses, and as the…

The post How Killer Rice Crippled Tokyo and the Japanese Navy appeared first on FeedBox.