Author: Maria Popova / Source: Brain Pickings

“The greatest poet in the English language found his poetry where poetry is found: in the lives of the people,” James BaldwinShakespeare, language as a tool of love, and the writer’s responsibility in a divided society. But while “the people” of sixteenth-century Europe were very different from the people of twentieth-century America, as were their lives, cultural representations of “the people” of our time and place — of what Whitman celebrated as “a great, aggregated, real PEOPLE, worthy the name, and made of develop’d heroic individuals” — have remained woefully stagnant and unreflective of diversity in the centuries since Shakespeare.

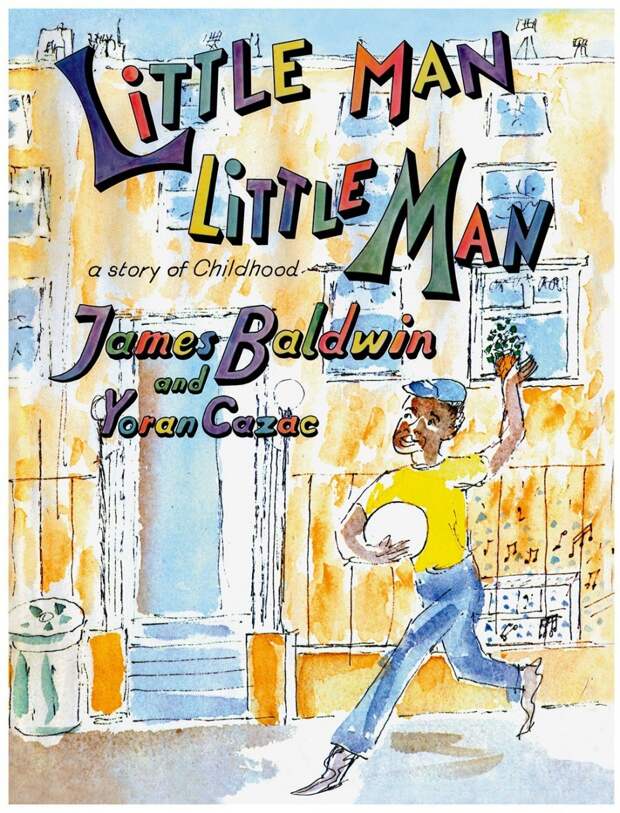

Fifteen years after Gwendolyn Brooks — the first black writer to win a Pulitzer Prize — released her trailblazing poems for kids celebrating diversity and the universal spirit of childhood, Baldwin set out to broaden the landscape of representation in children’s literature by composing a short, playful yet poignant story inspired by his own nephew — Tejan Kafera-Smart, or TJ. Originally published in 1976, with a jacket that billed it as “a child’s story for adults,” Little Man, Little Man: A Story of Childhood (public library) is Baldwin’s addition to the compact canon of sole children’s books composed by literary icons for their own kin, including Sylvia Plath’s The Bed Book, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Mr. Bliss, and William Faulkner’s The Wishing Tree.

The book is less a story than a series of vignettes depicting African American life and childhood on a particular block on New York City’s Upper West Side — one that looks “a little like the street in the movies or the TV when the cop cars come from that end of the street and then they come from the other end of the street.” Baldwin, who considered the book a “celebration of the self-esteem of black children,” began working on it shortly after his historic conversation about race with anthropologist Margaret Mead and set out to find the right illustrator for it.

He chose Yoran Cazac, a white French artist he had met more than a decade earlier through a mutual friend — the African American painter Beauford Delaney, who had mentored the young Baldwin and had taught him what it really means to see. When Delaney was diagnosed with schizophrenia and committed to a psychiatric asylum outside of Paris, Baldwin and Cazac rekindled their friendship in this hour of devastation and sorrow, and soon began collaborating on bringing Little Man, Little Man to life.

Cazac would complete the art — pencil and watercolor, vibrant and alive, evocative of children’s jubilant and free drawings — without having ever been to Harlem. Instead, Baldwin transported the artist by giving him books on black life, telling him stories about his time in New York, and sharing photographs of his own family there, including his nephew and niece, after whom the characters in the book were modeled. Cazac was determined to “imagine the unimaginable” through these telegraphic descriptions that became a form of artistic telepathy.

The story is written in the authentic colloquial language — children’s language, African American language — of its time and place. It is a creative choice that embodies poet Elizabeth Alexander’s notion of “the self in language” and evokes a sentiment from the stunning speech on the power of language Toni Morrison delivered when she became the first African American woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature: “We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.”

In the introduction to the 2018 edition of Little Man, Little Man, scholars Nicholas Boggs and Jennifer DeVere Brody quote from Baldwin’s essay “If Black English Isn’t a Language, Then Tell Me What Is?”:

It is not the black child’s language that is despised. It is his experience. A child cannot be taught by anyone who…

The post Little Man, Little Man: James Baldwin’s Only Children’s Book, Celebrating the Art of Seeing and Black Children’s Self-Esteem appeared first on FeedBox.