Author: Daniel Crown / Source: Atlas Obscura

Like so many of his peers in the hospitality industry, Paul Lake, the manager of Baltimore’s Rennert Hotel, spent the early weeks of March 1933 glued to his local newspaper stand.

In the months leading up to then, reports out of Washington D.C. had suggested politicians were flirting with a repeal of the 18th Amendment. While the wholesale abolishment of Prohibition would take months—if not years—to wriggle its way through the United States Congress, rumor had it legislators were considering a bill that would immediately legalize certain beers and wines. Lake could only imagine how such a law might increase profit margins in his hotel restaurant.On March 22, 1933, the bill passed. Known as the Cullen-Harrison Act, it only decriminalized beverages below 3.2 percent alcohol by weight. Still, this detracted little from what would later become known unofficially as “New Beer’s Eve.” After 13 long years, alcohol would once again flow in Lake’s hotel starting on April 7, at 12:01 a.m.

Lake didn’t scrimp on pomp and circumstance. To tend bar that night, he re-hired the last two bartenders to work at the Rennert before Prohibition. He installed a brand-new countertop on his bar, and, hoping to attract Baltimore’s press, he shrewdly invited the city’s most famous living writer: H.L. Mencken. Renowned for his polemics against puritanical America, Mencken was also a notorious beer enthusiast.

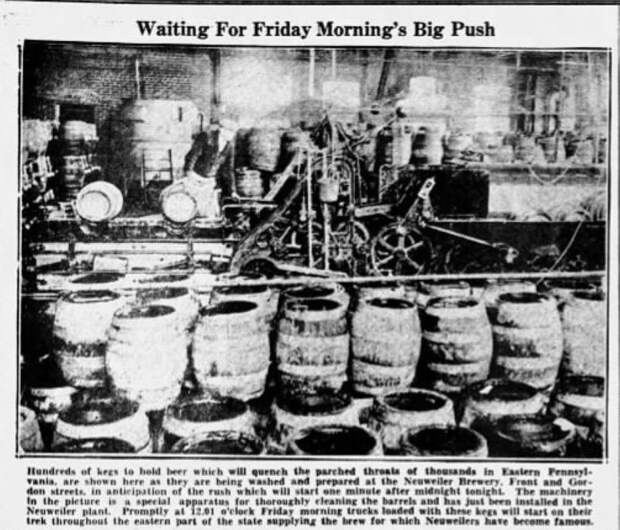

“There is nothing I would like better than to personally hand you the first glass of beer at the reopening,” Lake wrote to Mencken on March 31—to which the writer promptly responded, “Needless to say, I will be delighted.”When April 6 finally came, Lake ensured his delivery men were among the first in line at the Baltimore Brewery, which had promised to wheel out kegs at midnight. A hotel employee soon returned with a fresh barrel, and Lake ordered his bartenders to tap the keg. The dense crowd initially groaned as a stream of murky water rushed out. “But presently,” the Baltimore Sun gushed, “the milky brew rushed forth, eager, gurgling, foaming and spattering in its excitement.”

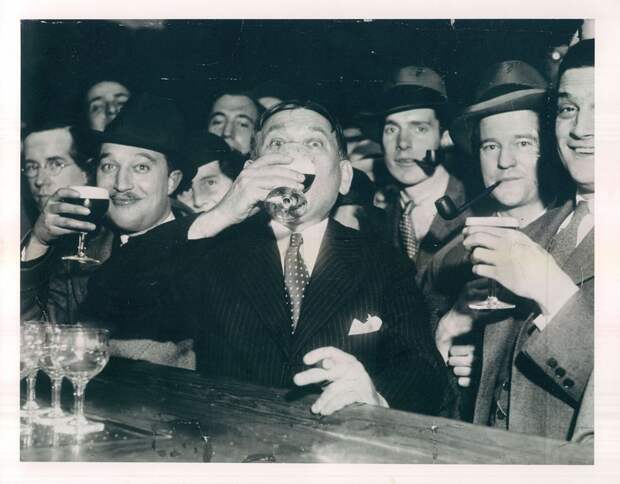

At 12:29, the bartenders passed their first successful pour to Lake, who then handed it to Mencken. The writer accepted it with a smile, cocked his drinking elbow, and took a dramatic pose.

“Here it goes!” he said.

As Mencken downed the beer in two long gulps, the audience silently anticipated his appraisal.

“Pretty good,” Mencken said, still smiling. “Not bad at all.”

As it turns out, Mencken was lying. The beer was actually “sad hog-wash,” he later admitted. Still, for him and other anti-Prohibition provocateurs, the brew’s quality was insignificant. What really mattered was that the scales of public sentiment were finally tipping their way. “America had largely become a beer-drinking country by 1920, when the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act both went into effect,” says historian William Rorabaugh, author of Prohibition: A Concise History. “As far as a majority of Americans were concerned, legal beer was the end of Prohibition.”

Many legislators in the federal government shared this view. Signed by President Franklin Roosevelt on March 22, 1933, the Cullen-Harrison Act came during the peak of the Great Depression. Viewing the 18th Amendment as a roadblock to recovery, the Roosevelt administration had already launched a…

The post The Day Americans Drank Breweries Dry appeared first on FeedBox.