Author: Lisa Grossman / Source: Science News

With a mortar and pestle, Christy Till blends together the makings of a distant planet. In her geology lab at Arizona State University in Tempe, Till carefully measures out powdered minerals, tips them into a metal capsule and bakes them in a high-pressure furnace that can reach close to 35,000 times Earth’s atmospheric pressure and 2,000° Celsius.

In this interplanetary test kitchen, Till and colleagues are figuring out what might go into a planet outside of our solar system.

“We’re mixing together high-purity powders of silica and iron and magnesium in the right proportions to make the composition we want to study,” Till says. She’s starting with the makings of what might resemble a rocky planet that’s much different from Earth. “We literally make a recipe.”

Scientists have a few good ideas for how to concoct our own solar system. One method: Mix up a cloud of hydrogen and helium, season generously with oxygen and carbon, and sprinkle lightly with magnesium, iron and silicon. Condense and spin until the cloud forms a star surrounded by a disk. Let rest about 10 million years, until a few large lumps appear. After about 600 million years, shake gently.

But that’s only one recipe in the solar systems cookbook. Many of the planets orbiting other stars are wildly different from anything seen close to home. As the number of known exoplanets has climbed — 3,717 confirmed as of April 12 — scientists are creating new recipes.

Seven of those exoplanets are in the TRAPPIST-1 system, one of the most exciting families of planets astronomers have discovered to date.

At least three TRAPPIST-1 planets might host liquid water on their surface, making them top spots to look for signs of life (SN: 12/23/17, p. 25).Yet those planets shouldn’t exist. Astronomers calculated that the small star’s preplanet disk shouldn’t have contained enough rocky material to make even one Earth-sized orb, says astrophysicist Elisa Quintana of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. Yet the disk whipped up seven.

TRAPPIST-1 is just one of the latest in a long line of rule breakers. Other systems host odd characters not seen in our solar system: super-Earths, mini-Neptunes, hot Jupiters and more. Many exoplanets must have had chaotic beginnings to exist where we find them.

These oddballs raise exciting questions about how solar systems form. Scientists want to know how much of a planet’s ultimate fate depends on its parent star, which ingredients are essential for planet building and which are just frosting on the planetary cake.

NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, which launched April 18, should bring in some answers. TESS is expected to find thousands more exoplanets in the next two years. That crowd will help illuminate which planetary processes are the most common — and will help scientists zero in on the best planets to check for signs of life.

| |

Beyond the bare necessities

All solar system recipes share some basic elements. The star and its planets form from the same cloud of gas and dust. The densest region of the cloud collapses to form the star, and the remaining material spreads itself into a rotating disk, parts of which will eventually coalesce into planets. That similarity between the star and its progeny tells Till and other scientists what to toss into the planetary stand mixer.

“If you know the composition of the star, you can know the composition of the planets,” says astronomer Johanna Teske of the Carnegie Observatories in Pasadena, Calif. A star’s composition is revealed in the wavelengths of light the star emits and absorbs.

When a planet is born can affect its final makeup, too. A gas giant like Jupiter first needs a rocky core about 10 times Earth’s mass before it can begin gobbling up gas. That much growth probably happens well before the disk’s gas disappears, around 10 million years after the star forms. Small, rocky planets like Earth probably form later.

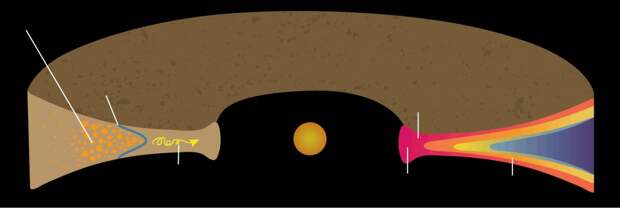

Finally, location matters. Close to the hot star, most elements are gas, which is no help for building planets from scratch. Where the disk cools toward its outer edge, more elements freeze to solid crystals or condense onto dust grains. The boundary where water freezes is called the snow line. Scientists thought that water-rich planets must either form beyond their star’s snow line, where water is abundant, or must have water delivered to them later (SN: 5/16/15, p. 8). Giant planets are also thought to form beyond the snow line, where there’s more material available.

But the material in the disk might not stay where it began, Teske says. “There’s a lot of transport of material, both toward and away from the star,” she says. “Where that material ends up is going to impact whether it goes into planets and what types of planets form.” The amount of mixing and turbulence in the disk could contribute to which page of the cookbook astronomers turn to: Is this system making a rocky terrestrial planet, a relatively small but gaseous Neptune or a massive Jupiter?

In the disk around a star, giant planets form beyond the “snow line,” where water freezes and more solids are available. Turbulence closer in knocks things around.

Source: T. Henning and D. Semenov/Chemical Reviews 2013

Like that roiling disk material, a full-grown planet can also travel far from where it formed.

Consider “Hoptunes” (or hot Neptunes), a new class of planets first named in December in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Hoptunes are between two and six times Earth’s size (as measured by the planet’s radius) and sidled up close to their stars, orbiting in less than 10 days. That close in, there shouldn’t have been enough rocky material in the disk to form such big planets. The star’s heat should mean no solids, just gases.

Hoptunes share certain characteristics — and unanswered questions — with hot Jupiters, the first type of exoplanet discovered, in the mid-1990s.

“Because we’ve known about hot Jupiters for so long, some people kind of think they’re old hat,” says astronomer Rebekah Dawson of Penn State, who coauthored a review about hot Jupiters posted in January at arXiv.org. “But we still by no means have a consensus about how they got so close to their star.”

Since the first known hot Jupiter, 51 Pegasi b, was confirmed in 1995, two explanations for that proximity have emerged. A Jupiter that formed past the star’s snow line could migrate in smoothly through the disk by trading orbital positions with the disk material itself in a sort of gravitational do-si-do. Or interactions with other planets or

The post The recipes for solar system formation are getting a rewrite appeared first on FeedBox.