Author: Lisa Grossman / Source: Science News

The existence of supermassive black holes in the early universe has never made much sense to astronomers.

Sightings since 2006 have shown that gargantuan monsters with masses of at least a billion suns were already in place when the universe was less than a billion years old – far too early for them to have formed by conventional means.One or two of these old massive objects could be dismissed as freaks, says theoretical astrophysicist Priyamvada Natarajan of Yale University. But to date, astronomers have spotted more than 100 supermassive black holes that existed before the universe was 950 million years old. “They’re too numerous to be freaks now,” she says. “You have to have a natural explanation for how these things came to be.”

The usual hypotheses are that these black holes were either born unexpectedly big, or grew up fast. But recent finds are challenging even those theories and may force astronomers to rethink how these black holes grow.

In the modern universe, black holes typically form from massive stars that collapse under their own gravity at the ends of their lives. They usually start out smaller than 100 solar masses and can grow either by merging with another black hole (SN: 3/19/16, p. 10) or by accreting gas from their environment (SN Online: 12/6/17).

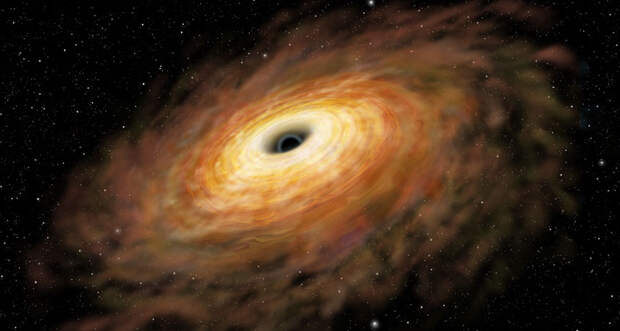

That gas often organizes itself into a disk that spirals into the black hole, with friction heating the disk to white-hot temperatures that create a brilliant glow visible across billions of light-years.

These black holes feeding on gas are called quasars. The faster a quasar eats, the brighter its disk glows.But the glow from that gas also limits the black hole’s growth: The bright disk’s photons push away fresh material. That sets a physical limit on how fast black holes of a given mass can grow. Astronomers express how fast a black hole is eating with a term called the Eddington ratio, measuring the black hole’s actual brightness in relation to the brightness it would have if it were eating as fast as it possibly could.

Astronomers have measured Eddington ratios for only about 20 supermassive black holes in the early universe. Most seem to be eating at the limit, in contrast to quasars in the present-day universe that feed at about a tenth that speed. Those furious feeding rates still seem to defy the black holes’ supermassive size: A 100-solar-mass black hole accreting at the limit should take about 800 million years to reach a billion solar masses, even taking into account that it would eat faster as it grew. And that 800 million years doesn’t include the time it took the initial black hole seed to form.

But physicist Myungshin Im of Seoul National University in South Korea and colleagues worried that previous observations were missing pickier eaters because fast eaters are brighter and easier to spot. If some early massive black holes were lazy eaters, their super sizes become even more puzzling — and may rule out some theories for how they grew.

So the team deliberately sought out dimmer distant quasars in a September 2015 observing run at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile.

The researchers found IMS J2204+0112, a billion-solar-mass black hole eating…

The post Astronomers can’t figure out why some black holes got so big so fast appeared first on FeedBox.