Author: Tom Siegfried / Source: Science News

Every field of science has its favorite anniversary.

For physics, it’s Newton’s Principia of 1687, the book that introduced the laws of motion and gravity. Biology celebrates Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) along with his birthday (1809). Astronomy fans commemorate 1543, when Copernicus placed the sun at the center of the solar system.

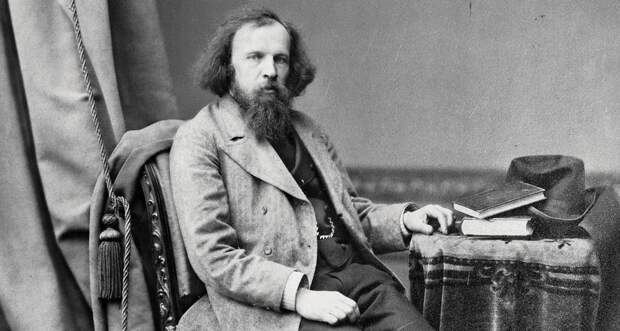

And for chemistry, no cause for celebration surpasses the origin of the periodic table of the elements, created 150 years ago this March by the Russian chemist Dmitrii Ivanovich Mendeleev.

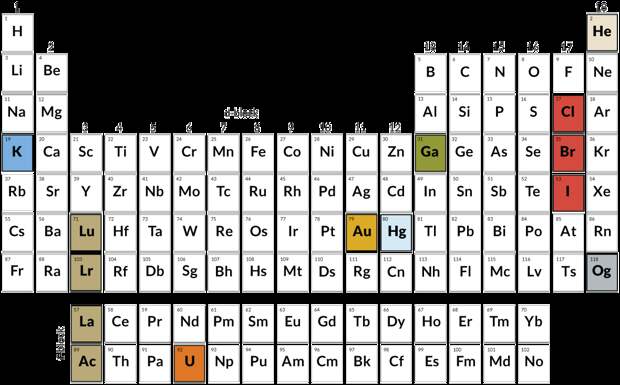

Mendeleev’s table has become as familiar to chemistry students as spreadsheets are to accountants. It summarizes an entire science in 100 or so squares containing symbols and numbers. It enumerates the elements that compose all earthly substances, arranged so as to reveal patterns in their properties, guiding the pursuit of chemical research both in theory and in practice.

“The periodic table,” wrote the chemist Peter Atkins, “is arguably the most important concept in chemistry.”

Mendeleev’s table looked like an ad hoc chart, but he intended the table to express a deep scientific truth he had uncovered: the periodic law. His law revealed profound familial relationships among the known chemical elements — they exhibited similar properties at regular intervals (or periods) when arranged in order of their atomic weights — and enabled Mendeleev to predict the existence of elements that had not yet been discovered.

“Before the promulgation of this law the chemical elements were mere fragmentary, incidental facts in Nature,” Mendeleev declared. “The law of periodicity first enabled us to perceive undiscovered elements at a distance which formerly was inaccessible to chemical vision.”

Mendeleev’s table did more than foretell the existence of new elements. It validated the then-controversial belief in the reality of atoms. It hinted at the existence of subatomic structure and anticipated the mathematical apparatus underlying the rules governing matter that eventually revealed itself in quantum theory. His table finished the transformation of chemical science from the medieval magical mysticism of alchemy to the realm of modern scientific rigor. The periodic table symbolizes not merely the constituents of matter, but the logical cogency and principled rationality of all science.

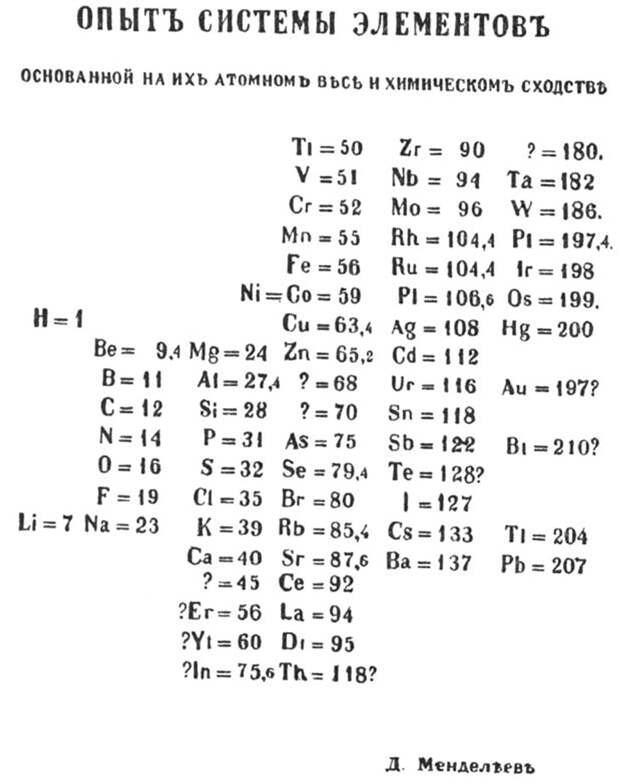

Mendeleev’s periodic table, published in 1869, was a vertical chart that organized 63 known elements by atomic weight. This arrangement placed elements with similar properties into horizontal rows. The title, translated from Russian, reads: “Draft of system of elements: based on their atomic masses and chemical characteristics.”

Legend has it that Mendeleev conceived and created his table in a single day: February 17, 1869, on the Russian calendar (March 1 in most of the rest of the world). But that’s probably an exaggeration. Mendeleev had been thinking about grouping the elements for years, and other chemists had considered the notion of relationships among the elements several times in the preceding decades.

In fact, German chemist Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner noticed peculiarities in groupings of elements as early as 1817. In those days, chemists hadn’t yet fully grasped the nature of atoms, as described in the atomic theory proposed by English schoolteacher John Dalton in 1808. In his New System of Chemical Philosophy, Dalton explained chemical reactions by assuming that each elementary substance was made of a particular type of atom.

Chemical reactions, Dalton proposed, produced new substances when atoms were disconnected or joined. Any given element consisted entirely of one kind of atom, he reasoned, distinguished from other kinds by weight. Oxygen atoms weighed eight times as much as hydrogen atoms; carbon atoms were six times as heavy as hydrogen, Dalton believed. When elements combined to make new substances, the amounts that reacted could be calculated with knowledge of those atomic weights.

Dalton was wrong about some of the weights — oxygen is really 16 times the weight of hydrogen, and carbon is 12 times heavier than hydrogen. But his theory made the idea of atoms useful, inspiring a revolution in chemistry. Measuring atomic weights accurately became a prime preoccupation for chemists in the decades that followed.

When contemplating those weights, Döbereiner noted that certain sets of three elements (he called them triads) showed a peculiar relationship. Bromine, for example, had an atomic weight midway between the weights of chlorine and iodine, and all three elements exhibited similar chemical behavior. Lithium, sodium and potassium were also a triad.

Every element on this venerated table has its own story. All together, they capture the entire repertoire of known chemistry. Read up on the tales between the lines.

Other chemists perceived links between atomic weights and chemical properties, but it was not until the 1860s that atomic weights had been well enough understood and measured for deeper insights to emerge. In England, the chemist John Newlands noticed that arranging the known elements in order of increasing atomic weight produced a recurrence of chemical properties every eighth element, a pattern he called the “law of octaves” in an 1865 paper. But Newlands’ pattern did not hold up very well after the first couple of octaves, leading a critic to suggest that he should try arranging the elements in alphabetical order instead. Clearly, the relationship of element properties and atomic weights was a bit more complicated, as Mendeleev soon realized.

Born in Tobolsk, in Siberia, in 1834 (his parents’ 17th child), Mendeleev lived a dispersed life, pursuing multiple interests and traveling a higgledy-piggledy path to prominence. During his higher education at a teaching institute in St. Petersburg, he nearly died from a serious illness. After graduation, he taught at middle schools (a requirement of his scholarship at the teaching institute), and while teaching math and science, he conducted research for his master’s degree.

He then worked as a…

The post 150 years on, the periodic table has more stories than it has elements appeared first on FeedBox.