Trumpeted by the press as “the great eclipse of the nineteenth century,” the total solar eclipse of August 7, 1869 was the world’s first astronomical event marketed as popular entertainment — not merely a pinnacle of excitement for the scientific community, but a celestial spectator sport for laypeople.

Smoked, stained, or vanished glass sold faster than any other item in American stores that summer. Small towns on the eclipse path, which stretched from Alaska to the mid-Atlantic coast, experienced an unprecedented surge of tourism. Newspapers offered extensive coverage of the event in the weeks leading up to it, crowned by front-page headlines the morning after the eclipse.But by far the most exquisite and original piece about the cosmic marvel came two months later from the inimitable Maria Mitchell (August 1, 1818–June 28, 1889) — America’s first female astronomer, who paved the way for women in science and became the first woman hired by the United States federal government for a “specialized nondomestic skill” in her capacity as “computer of Venus” — a one-woman GPS guiding sailors around the world.

Writing in the October issue of Hours at Home, Scribner’s first magazine, Mitchell reported on the eclipse expedition she had led to Burlington, Vermont. (Nearly a decade later, she would draw on this experience and a subsequent one in her tips on how to watch a solar eclipse.) Fusing rigorous insight into the science of eclipses with a poetic account of this uncommonly transcendent encounter with the universe, Mitchell ends her anonymous essay with a clever rhetorical twist that throws a grenade into society’s most foundational assumptions about science, gender, and human nature.

She begins by framing the enormity of the fanfare surrounding the event, summoning the throngs “ticketed to totality”:

Every known astronomer received courteous invitations into the shadow. Every astronomer, professional or amateur, prepared to go. The observatories must have been left undirected; the mathematical chairs of the colleges must have been empty, and, judging from the crowded condition of hotels within the darkness, Saratoga and Newport must have felt the different set of the travelling current… In the halls of the hotels we saw meetings between friends long separated, and heard joyous exclamations as grayhaired men met and shook hands and laughed, that neither could recognize in the middle-aged other the youth whom he had left, and whom he had since known only through scientific journals.

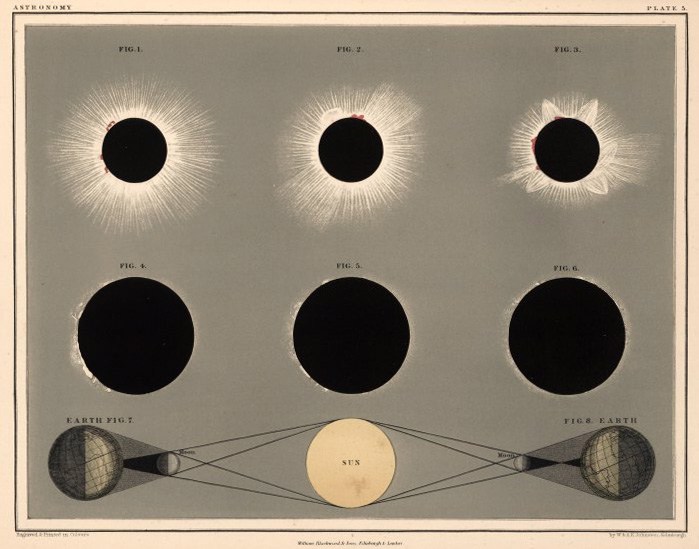

Leading a team of six young scientists, Mitchell arrived at Burlington College on August 4, “too late to attempt any work that day,” and was engulfed in inclement weather for the next two days, glooming from cloudy to “rainy, rainy all day.” When the third day broke with “as beautiful as morning could be,” they began setting up their instruments. Writing deliberately in the masculine, she describes the technical setup:

In preparing for an observation of time, the astronomer gives himself every possible facility. He ascertains to a tenth of a second the condition of his chronometer, not only how fast or how slow it is, but how much that fastness or that slowness varies from hour to hour. He notes exactly the second and part of a second when the expected event should arrive; and a short time before that he places himself at the telescope.

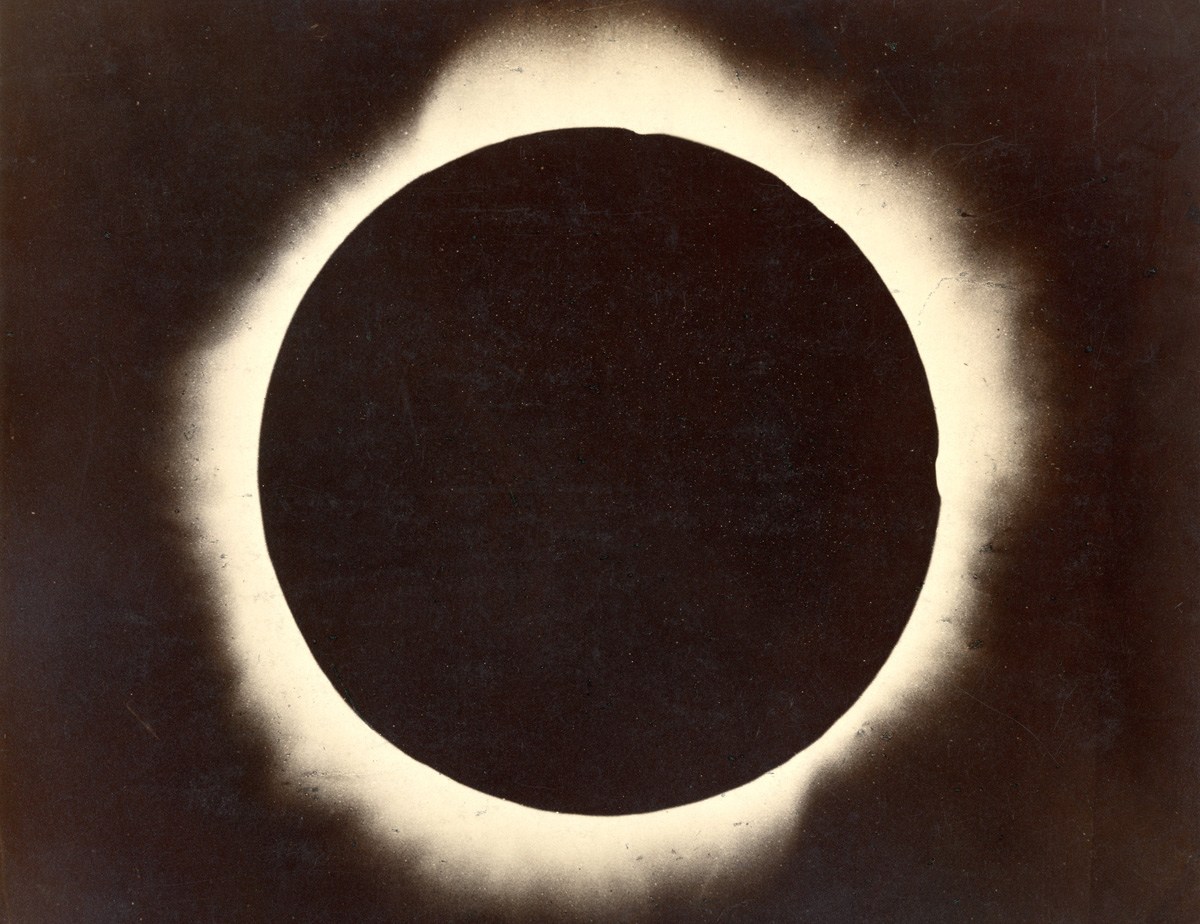

Mitchell then pivots smoothly from this matter-of-factly reportage to a lyrical account of the pinnacle of the experience — the sight of the corona and its attendant otherworldly light:

There were some seconds of breathless suspense, and then the inky blackness appeared on the burning limb of the sun. All honor to my assistant, whose uniform count on and on, with unwavering voice, steadied my nerves! That for which we had travelled fifteen hundred miles had really come. We watched the movement of the moon’s black disk across the less…

The post The World’s First Celestial Spectator Sport: Astronomer Maria Mitchell’s Stunning Account of the 1869 Total Solar Eclipse appeared first on FeedBox.