“Life is not what one lived, but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it,” Gabriel García Márquez asserted in immortalizing the memory of his own life. And yet however much truth the sentiment may hold, it holds twice as much tragedy — although memory is the seedbed of our sense of self, the vast majority of life unfolds in the small, unremembered moments that furnish the microscopic threads in the tapestry of being.

Sally Mann captured this paradox in her exquisite meditation on the dark side of memory: “The exercise of our memory does not bring us closer to the past but draws us farther away.”Memory, then, is not the pencil with which the outline of a life is drawn but the eraser — something as true of our personal memory as it is of our collective memory, which contains everything we know as culture: the great works of art celebrated generations after their creators have returned to stardust, the scientific discoveries that become the building blocks of subsequent theories and breakthroughs.

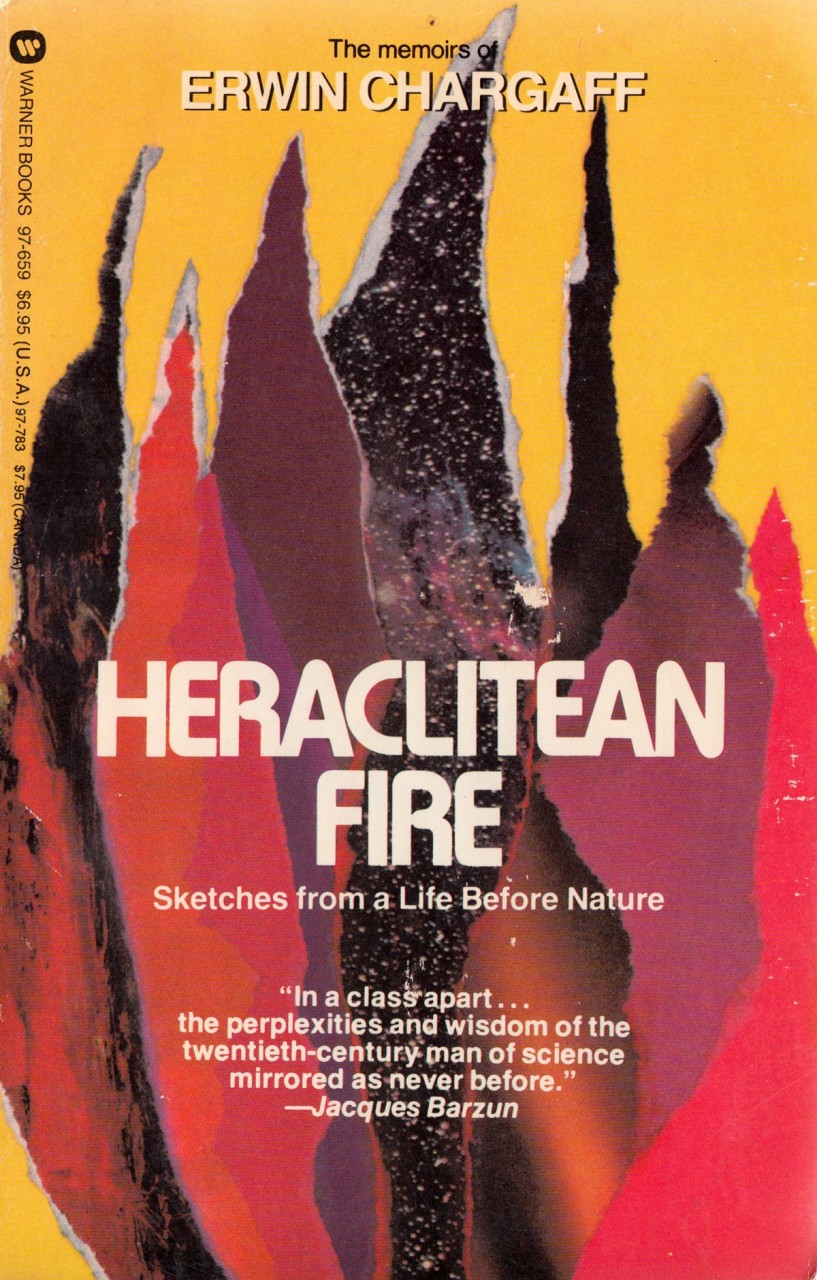

Perhaps because science is the ultimate self-correcting mechanism and necessarily builds on both the errors and the triumphs of the past, scientists must have a particularly revealing perspective on memory and its paradoxes. That’s what pioneering biochemist Erwin Chargaff (August 11, 1905–June 20, 2002) explores in a passage…

The post A Pioneering Scientist on Memory, the Value of Our Unremembered Work, and the Incalculable Sum Total of the Human Experience appeared first on FeedBox.