Author: Maria Temming / Source: Science News

Scrolling through a news feed often feels like playing Two Truths and a Lie.

Some falsehoods are easy to spot. Like reports that First Lady Melania Trump wanted an exorcist to cleanse the White House of Obama-era demons, or that an Ohio school principal was arrested for defecating in front of a student assembly.

In other cases, fiction blends a little too well with fact. Was CNN really raided by the Federal Communications Commission? Did cops actually uncover a meth lab inside an Alabama Walmart? No and no. But anyone scrolling through a slew of stories could easily be fooled.We live in a golden age of misinformation. On Twitter, falsehoods spread further and faster than the truth (SN: 3/31/18, p. 14). In the run-up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the most popular bogus articles got more Facebook shares, reactions and comments than the top real news, according to a BuzzFeed News analysis.

Before the internet, “you could not have a person sitting in an attic and generating conspiracy theories at a mass scale,” says Luca de Alfaro, a computer scientist at the University of California, Santa Cruz. But with today’s social media, peddling lies is all too easy — whether those lies come from outfits like Disinfomedia, a company that has owned several false news websites, or a scrum of teenagers in Macedonia who raked in the cash by writing popular fake news during the 2016 election.

Most internet users probably aren’t intentionally broadcasting bunk. Information overload and the average Web surfer’s limited attention span aren’t exactly conducive to fact-checking vigilance. Confirmation bias feeds in as well. “When you’re dealing with unfiltered information, it’s likely that people will choose something that conforms to their own thinking, even if that information is false,” says Fabiana Zollo, a computer scientist at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice in Italy who studies how information circulates on social networks.

Intentional or not, sharing misinformation can have serious consequences. Fake news doesn’t just threaten the integrity of elections and erode public trust in real news. It threatens lives. False rumors that spread on WhatsApp, a smartphone messaging system, for instance, incited lynchings in India this year that left more than a dozen people dead.

To help sort fake news from truth, programmers are building automated systems that judge the veracity of online stories. A computer program might consider certain characteristics of an article or the reception an article gets on social media. Computers that recognize certain warning signs could alert human fact-checkers, who would do the final verification.

Automatic lie-finding tools are “still in their infancy,” says computer scientist Giovanni Luca Ciampaglia of Indiana University Bloomington. Researchers are exploring which factors most reliably peg fake news. Unfortunately, they have no agreed-upon set of true and false stories to use for testing their tactics. Some programmers rely on established media outlets or state press agencies to determine which stories are true or not, while others draw from lists of reported fake news on social media. So research in this area is something of a free-for-all.

But teams around the world are forging ahead because the internet is a fire hose of information, and asking human fact-checkers to keep up is like aiming that hose at a Brita filter. “It’s sort of mind-numbing,” says Alex Kasprak, a science writer at Snopes, the oldest and largest online fact-checking site, “just the volume of really shoddy stuff that’s out there.”

Reader referrals

Visitors to real news websites mainly reach those sites directly or from search engine results. Fake news sites attract a much higher share of their incoming web traffic through links on social media.

Substance and style

When it comes to inspecting news content directly, there are two major ways to tell if a story fits the bill for fraudulence: what the author is saying and how the author is saying it.

Ciampaglia and colleagues automated this tedious task with a program that checks how closely related a statement’s subject and object are. To do this, the program uses a vast network of nouns built from facts found in the infobox on the right side of every Wikipedia page — although similar networks have been built from other reservoirs of knowledge, like research databases.

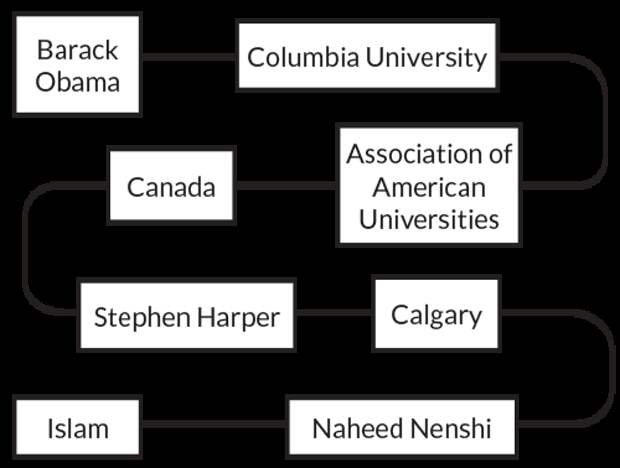

In the Ciampaglia group’s noun network, two nouns are connected if one noun appeared in the infobox of another. The fewer degrees of separation between a statement’s subject and object in this network, and the more specific the intermediate words connecting subject and object, the more likely the computer program is to label a statement as true.

Take the false assertion “Barack Obama is a Muslim.” There are seven degrees of separation between “Obama” and “Islam” in the noun network, including very general nouns, such as “Canada,” that connect to many other words. Given this long, meandering route, the automated fact-checker, described in 2015 in PLOS ONE, deemed Obama unlikely to be Muslim.

An automated fact-checker judges the assertion “Barack Obama is a Muslim” by studying degrees of separation between the words “Obama” and “Islam” in a noun network built from Wikipedia info. The very loose connection between these two nouns suggests the statement is false.

Source: G.L. Ciampaglia et al/PLOS One 2015

But estimating the veracity of statements based on this kind of subject-object separation has limits. For instance, the system deemed it likely that former President George W. Bush is married to Laura Bush. Great. It also decided George W. Bush is probably married to Barbara Bush, his mother. Less great. Ciampaglia and colleagues have been working to give their program a more nuanced view of the relationships between nouns in the network.

Verifying every statement in an article isn’t the only way to see if a story passes the smell test. Writing style may be another giveaway. Benjamin Horne and Sibel Adali, computer scientists at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y., analyzed 75 true articles from media outlets deemed most trustworthy by Business Insider, as well as 75 false stories from sites on a blacklist of misleading websites. Compared with real news, false articles tended to be shorter and more repetitive with more adverbs. Fake stories also had fewer quotes, technical words and nouns.

Based on these results, the researchers created a computer program that used the four strongest distinguishing factors of fake news…

The post People are bad at spotting fake news. Can computer programs do better? appeared first on FeedBox.