Usually, the re-working and rerelease of a classic recording signifies nothing more than a sneaky cash-grab by a record company, a producer, a recording engineer, or an artist’s estate. (Many of us have assumed a permanent defensive crouch in anticipation of the avalanche of unreleased Prince recordings his estate is sure to authorize.

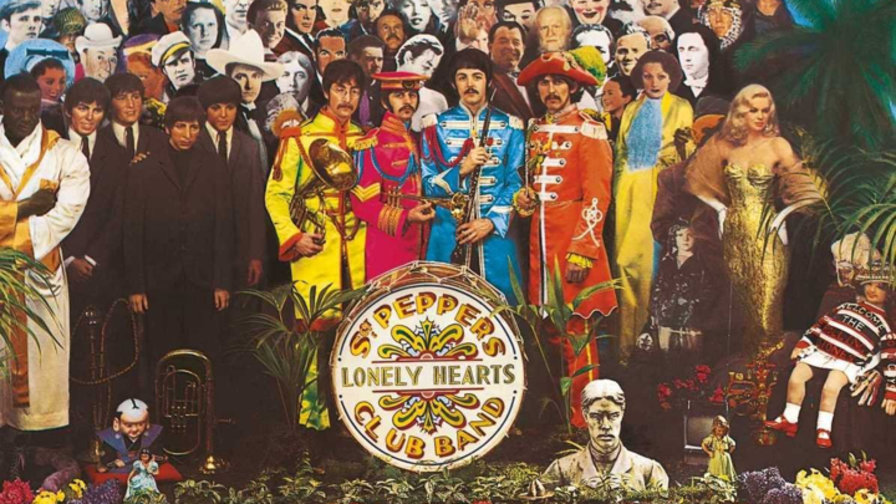

) Why else would you mess with recordings that people already know, love, and own? You wouldn’t want a re-painted Mona Lisa, would you? Music and art of things of their time, and should generally therefore be left as is. In June, to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the release of their 1966 Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, The Beatles organization released three remixed editions of their landmark album. This time, it’s different. It’s great. To understand why, you have to know a few things about recording technology.What’s a Remix? What’s a Remaster? What’s the Point?

Modern recordings are made up of different performances captured at different times and played them back together so that they sound like they occurred simultaneously. You could record, say, drums on one track, bass on another, guitar on a third track, and piano on another: When you play them back together, you’d sound like a band. It’s not uncommon for hit recordings to have hundreds of tracks within a single multitrack recording, with layer upon layer of vocals and instruments stacked into a single musical arrangement.

Nobody can play a multitrack recording as is at home or in their car as is. All of those tracks have to be combined — or “mixed” — into a second, listener-playable recording.

That’s what you buy, whether it’s a download, a CD, or a vinyl record. The mix may be monaural, which means it’s just a single track containing everything, or stereo, in which the recording’s sounds can be positioned in the space between two speakers. A multitrack can also be mixed into a Surround format, doing the same thing as stereo, but with more speakers positioned around the listener. Most modern recordings are in stereo, though in The Beatles’ heyday in England, mono was king; a stereo mix was merely a requirement for other world markets.Mixing — or “remixing,” which just means doing-over a mix — can be an art in and of itself. It involves balancing the volumes of the tracks, adjusting their tonal qualities, and adding effect such as reverb and echo. If the recording is the artist’s performance, the mix is the producer’s, and the recording engineer’s.

Once the mix is complete, it must be prepared for download, CD, or vinyl. This process is called “mastering.” Depending on how good the mix is, mastering involves either a small amount of tweaking, or is the last chance for tonal or dynamic repairs. Mastering for vinyl is especially tricky given the constraints etching audio signals into minuscule grooves on a spinning disk — if the bass content, for example, is too loud, the grooves collide and the disc is unplayable.

Vinyl mastering (STEREOPHILE.COM)

When records are reissued, it’s common to see them advertised as being “remixed” or “remastered.” Now you know the difference. If something’s

- remixed — the original tracks have recombined as a new mix.

- remastered — the original mix has been re-tweaked.

By the time The Beatles became popular, four-track machines were in use in England where they recorded. Most of their early Beatle hits were performed live, with just a few other layers, called “overdubs,” added later. If they ever wanted to add more than just a few extra bits, they could copy a mix of the four track onto another four-track machine — this is called “bouncing” — and then fill up its other tracks. In the pre-digital days of magnetic recording, each time the song was bounced, its quality degraded a little, so bouncing was kept to a minimum.

A 4-track recorder used by The Beatles

Beatles and Not-Beatles

The three original Beatles — John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and George Harrison — had always been ambivalent about continuing as a group. Mark Lewisohn’s excellent Tune In reveals that they disbanded a few times before breaking through. Once there was the possibility of making some real money by performing, though, the four intelligent, independent men — having added Ringo Starr — dedicated themselves to The Beatles business, for how long no one knew. Joined at the hip and caught in a maelstrom of their own inadvertent making, they toured for a few chaotic, non-stop years — with recording sessions squeezed in-between travel — before they announced in late summer 1966 that they would no longer be performing.

They split off into four directions, exploring what it would be like to be an individual artist and not…

The post Sgt. Pepper Wasn’t Broken. So They Fixed It. appeared first on FeedBox.