It’s September 8, 2017, at 7:10 p.m., and the Boston Red Sox are taking the field against the Tampa Bay Rays. The atmosphere is relaxed. It’s a home game, and the Sox are leading the American League East, coming into this series off a two-game win streak.

But nothing is over until it’s over, and it’s only the top of the first.Four levels above the on-field action, Josh Kantor, the park’s organist, has his own challenge to deal with. He’s trying to learn the theme song from Game of Thrones. “Somebody wanted to hear it,” he explains, his fingers working. “It’ll be a little bit of an adventure in about 40 seconds.”

The 40 seconds pass. “Drop It Like It’s Hot,” the DJ’s latest pick, fades out. Kantor’s organ cranks up, and Fenway Park transforms, briefly, into a land of war and dragons.

By the song’s end, there are two outs on the board. “That was pretty good!” I say. Kantor nods: “Passable.” In the stands, someone, somewhere, is smiling at his phone.

Everyone knows what a baseball game is like. There are the sights: bright green grass, striped ump shirts, bases that look tiny from the cheap seats. There are the tastes and smells—hot dogs, popcorn, sweat—and that pleasantly crushed feeling that comes with being taken out with the crowd. And there are the sounds: the crack of the bat, the rolling applause, and the wheezy, cheerful organ, which soars over everything like a solid double.

At first glance, it may seem like hardly anything about the experience of a professional baseball game changed in the last century.

But a trip to any modern ballpark offers a number of examples of how America’s pastime has evolved to face the future, whether it’s with big data or live fish. Thanks to musicians such as Josh Kantor, who use technology to find new possibilities in old-school entertainment, the organ is catching up, too.

This is baseball, so let’s get our stats straight at the outset. Kantor is 44 years old, and has been Fenway Park’s official organist since 2003. In his nearly 15 seasons with the Red Sox, he has missed exactly zero home games, which means that as of the end of September 8, he had been present for 1,239. During this time frame, the team’s home game win percentage has been a respectable .594, something Kantor occasionally, and half-jokingly,

When there’s a full house—which has happened fairly often since he started—Kantor is playing for 38,000 people, nearly twice as many as fit into the city’s next-largest music venue. You can hear him everywhere in the park, from the press box to the top of the Green Monster. But if you want to see him, you have to ride a few flights of escalators up to what he describes as his “non-glamorous perch” within the State Street Pavilion Club.

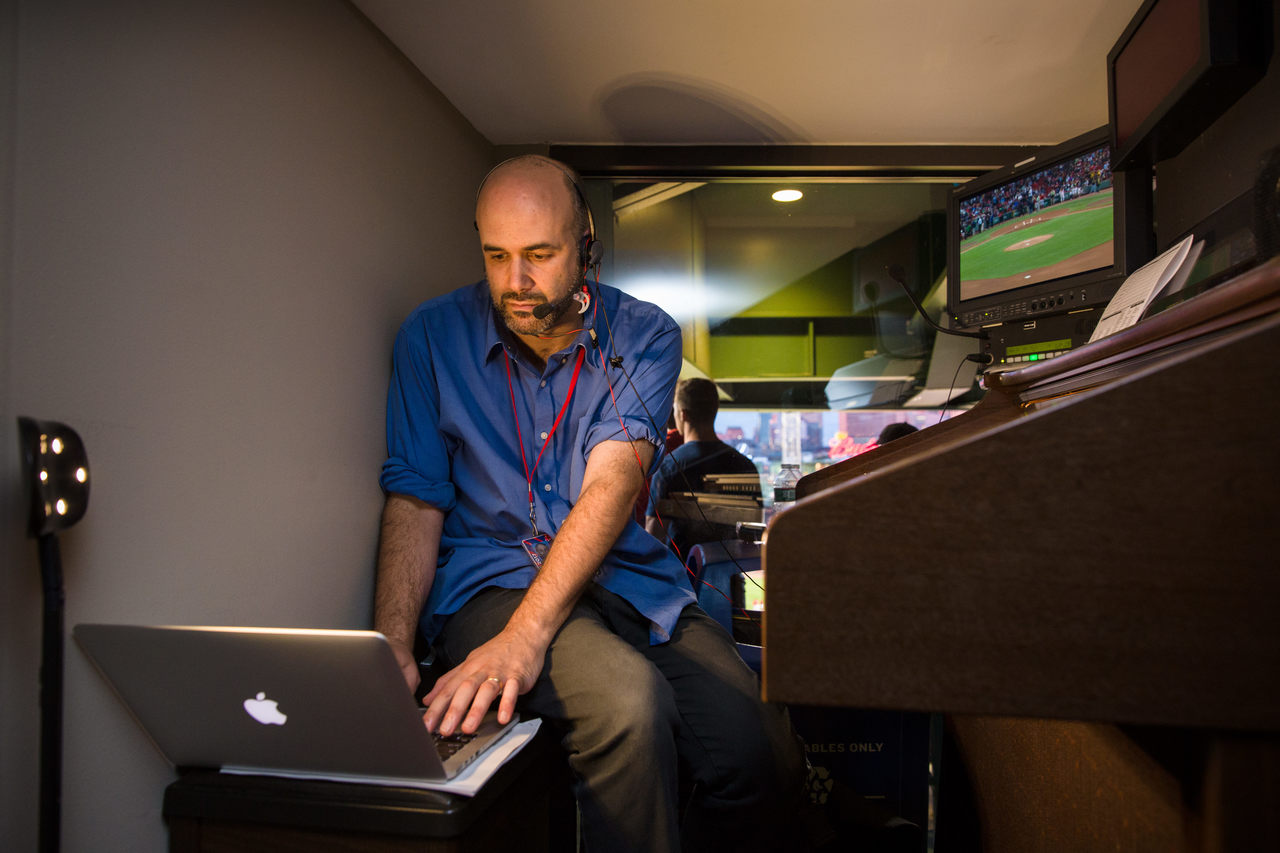

The club itself is ritzy—you can’t get in without a special season ticket—and it would be easy to mistake Kantor for a weird sort of hidden piano man, another amenity for exclusive guests. But a closer look reveals a larger operation. To Kantor’s right is his Macbook, opened on the padded piano bench, and a long-necked flexible lamp. To his left, there’s a window with a decent view of the first base line, and a briefcase-sized television, off for now. He’ll turn it on once the game starts, along with the red LED clock above it, which counts down the time left in the commercial breaks. Another huge screen—hung on the wall to his right, for the benefit of the Pavilion Club’s diners—is already going.

He’s wearing gray slacks, a blue button-down with the sleeves rolled up, a black headset microphone, and a pair of red earbuds that join just under his stubbled chin. (There’s another mic, fuzzy-headed, jutting out from the smaller television.) His cell phone is sitting on top of the organ, along with a small digital watch, which he’s placed face-up on the console, almost like a finishing touch.

The whole thing looks less like a traditional musician’s lair and more like an air traffic control booth, and in a way, it is: Kantor is constantly conversing with an entire production staff, which works together to keep the park’s audio well-oiled. “I’ve got eight conversations in this ear,” he says. “I’ve got the organ in this ear. I’ve got an extra earbud for figuring out songs. You learn what you can tune out.”’

Baseball organs aren’t quite as old as baseball. They’ve been a part of the sport since April 26, 1941, when Chicago’s Wrigley Field brought in a musician named Roy Nelson to entertain fans. He played a lot of then-popular music, but had to stop half an hour before a game actually began. (As the Chicago Tribune explained at the time, “his repertoire includes many restricted ASCAP arias, which would have been picked up by the radio microphones,” breaking copyright law.) Despite rave reviews—Sporting News praised his “restful, dulcet” playing—Nelson’s career lasted only two games. The next time the Cubs were out of town, stadium management quietly removed his organ.

Kantor is also generally not broadcast, for the same rights-related reasons. It’s a restriction that, paradoxically, gives him an enormous amount of freedom. He can play whatever he wants. His own favorite organist is Nancy Faust, who played for the White Sox from 1970 through 2010, and became famous for her clever song choices. If two people were running bases, she might treat the crowd to the Mario Bros. theme. Kantor approaches his soundtracking in a similar spirit, with a few twists of his own. “Happy 76th anniversary of MLB organ music,”

It also means that listening to him play is exclusively a live experience, a rarity in this time of cell phone cameras and instant concert recordings. At exactly 5:40 p.m., 90 minutes before the action starts, Kantor starts running through his own kind of warmup, a 35-minute medley meant to entertain the pre-game guests. To a rookie like me, the Pavilion Club offers near-endless distractions: soft puffs of air from the swinging restroom doors; the clatter of dropped forks; the smell of spicy fries, which comes in waves. Feet from us, a table full of businessmen loudly compare appetizers. Every once in a while, through the window, a ball arcs in and out of view. Outside, the players are warming up too.

Kantor, unfazed, moves seamlessly through decades and genres, trimming the fat from songs and stringing them together like Fenway Franks. He brings “Come On Eileen” straight from the first chorus into the slowed-down, catchy bridge, then moves into something classic-sounding that I can’t quite put my finger on. Around the sixth song, the guy checking tickets at the Pavilion’s back door comes over, leans against the…

The post The Very Modern Life of an Old-Timey Baseball Organist appeared first on FeedBox.