Author: Shoshi Parks / Source: Atlas Obscura

Of all the changes within Nicaragua to come out of the overthrow of the Somoza regime by the Sandinistas in 1979, perhaps the least anticipated was the birth of a new language.

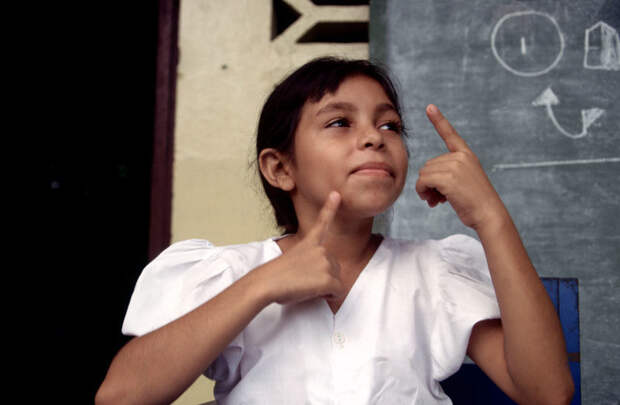

Nicaraguan Sign Language is the only language spontaneously created, without the influence of other languages, to have been recorded from its birth. And though it came out of a period of civil strife, it was not political actors but deaf children who created the language’s unique vocabulary, grammar, and syntax.When the Sandinista National Liberation Front gained power, they embarked on what has been described as a “literacy crusade,” developing programs to promote fluency in reading Spanish. One such initiative was opening the first public school for deaf education, the Melania Morales Special Education Center, in Managua’s Barrio San Judas. According to Ann Senghas, a professor of psychology at Barnard College who has studied NSL, it was the first time in the history of the country that deaf children were brought together in large numbers.

These children, who ranged in age from four to 16, had no experience with sign language beyond the “home signs” they used with family members to communicate broad concepts. American Sign Language, which has existed since the early 19th century, is used throughout the Americas and is often considered a “lingua franca” among deaf people whose first sign language is a national or regional one.

But the first Nicaraguan deaf school did not use ASL or any signs at all. Instead, they focused on teaching children to speak and lip-read Spanish.

This educational strategy, known as “oralism,” has long been a subject of debate in deaf education, one that was particularly fierce in the United States where ASL originated. Around the turn of the 20th century, some deaf-education advocates believed that the ability to speak and lip-read a language would be more beneficial to deaf individuals than “manualism,” communication via sign language. By learning English, they argued, deaf individuals would be able to fully participate in U.S. society.

English immersion for the deaf was part of a wider effort, epitomized by the eugenics movement, to stamp out differences within the American population. Among the most vocal proponents of eugenics when it came to the deaf community was the inventor of the telephone, Alexander Graham Bell. Bell argued that if deaf people were allowed to communicate via sign language, their isolation from the hearing population would lead to more deaf marriages and, consequently, a larger deaf population.

“Oralism, Bell believed, allowed deaf people to leave their educational and cultural corners and participate in society at large,” writes Brian H. Greenwald, professor of history at the deaf institution Gallaudet University, via email. Bell, Greenwald notes, “used oralism as a form of assimilation.” It was a strategy that Bell hoped would eventually lead to the eradication of deafness in American society.

In Managua in the 1980s, too, though free of the influence of eugenicists, the Sandinistas focus on Spanish literacy resulted in the immersion of deaf students in Spanish speaking and reading skills. But while the country’s deaf children were being taught Spanish inside the classroom, outside the classroom they were spontaneously developing their own method of signed communication.

Though older and younger students attended separate classes during school hours, on buses and playgrounds the children quickly began to select “conventions” for necessary words. Such conventions occur when a community of speakers, who at home may have all used different signs to refer to an object or action, begin to consistently default to using just one, says James Shepard-Kegl. Kegl is co-director…

The post How Deaf Children in Nicaragua Created a New Language appeared first on FeedBox.