Author: Vincent Gabrielle / Source: Atlas Obscura

It was 1911, and the Union of South Africa was awash with rumor and suspicion. It was said that there was a turncoat who had deserted the Ministry of Agriculture to sell secrets to a shadowy syndicate of American capitalists.

South Africa had only been autonomous—as a dominion of the British Empire—for about a year. Any disruption to a major industry could be very damaging to the fledgling country.In response, the parliament authorized a clandestine expedition to the Sahel, the semi-arid region south of the Sahara. The expedition was led by Russell Thornton, a veteran of the Boer War and two other “competent experts.” The alleged traitor? None other than Thornton’s brother, Earnest, a former employee of the Secretary of Agriculture.

Their mission was to secure a flock of ostriches—by any means necessary.

What’s the weirdest bird? The ostrich,” says Arne Moores, professor of biodiversity at Simon Fraser University, “They may be the most [evolutionarily] isolated species in the world.” Massive and flightless, ostriches thrive in arid environments, insulated from both heat and cold by their thick plumage. And they have the biggest bodies and largest eggs of any living avian. According to a 2014 study, ostriches and their closest relatives—the group including emus, cassowaries, and kiwis—diverged when there were still dinosaurs walking the earth. “They are different because they’re a long [evolutionary] branch, with a flowering at the end,“ explains Moores—two species and a couple of subspecies, ranging across central and southern Africa.

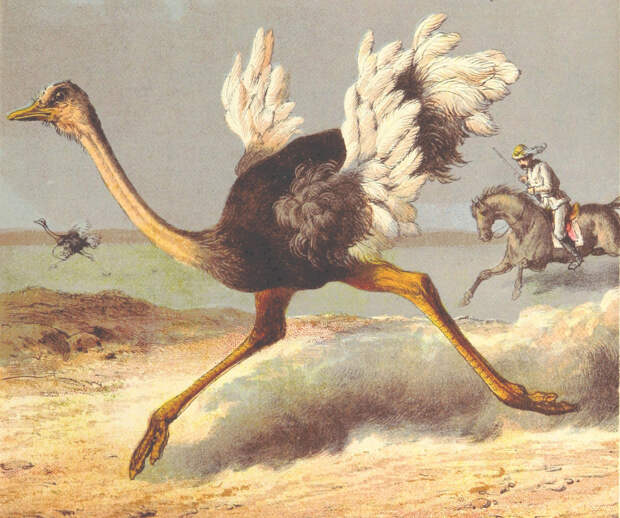

There were ostriches around when humans emerged, so we have a long history with the massive birds. Africans had long hunted ostriches for meat and leather. In ancient Egypt, the goddess Maat and divine justice were represented by the ostrich feather, and two of them adorned the crowns of pharaohs as a symbol of authority. Ostrich eggs were carved and given as offerings in ancient Greece, and later they were used to adorn minarets. In the Ottoman Empire, the Arabian ostrich was hunted for sport, and those showy feathers.

But it wasn’t until the last decades of the 19th century that ostriches—their feathers, in particular—became a global commodity.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, exotic plumes, wings, and whole, taxidermied birds (and other animals) were used to trim ever more elaborate women’s hats. By 1911 hats had reached their apex size, and ostrich feathers, due to their volume and versatility, were particularly prized and commanded hefty prices.

At the time, South Africa provided 85 percent of planet’s ostrich feathers. The remainder mostly came from North Africa, through traditional trans-Saharan trade routes, usually by camel. This new status quo was all very good for South Africa. Ostrich feathers were its third most lucrative export, and the government had seized land from indigenous people and Dutch Boer settlers to create ostrich farms. Oudtshoorn became known as a feather town, where thousands of people, largely Jewish refugees from Lithuania, worked in the trade. Oudtshoorn was known as “Little Jerusalem.”

But there was one problem. South Africa didn’t actually have the best feathers on the market. The highest prices were paid for plumage from “Barbary ostriches,” a mysterious variety thought to come from North Africa. The Barbary ostrich (a term now sometimes used to refer to North African ostriches) was said to have thicker, more luxurious feathers than South African birds. But in truth, by the time these feathers reached market, they had passed through so many hands that their European buyers didn’t really know where they had come from. The South African government, to strengthen its grip on the market, wanted to know.

The South Africans got a clue as to the provenance of the Barbary plumage some time around 1910, when a lush, lustrous, full feather—just the kind that fetched the highest prices—reached the hands of the British consul in Tripoli, with a hint as to its origins. The British officials were able to say that it had come from “Southern Soudan,” meaning the colonial holdings in West Africa sometimes known as French Sudan (roughly present-day Mali and Niger). The British passed this information to their close friends in South Africa.

This was the intelligence—a possible location for the near-mythic Barbary ostrich—that South African officials feared Earnest Thornton would leak to the upstart American ostrich industry. If growers in California and Arizona got to the Barbary ostrich first, South Africa could be cut out of the New York hat industry entirely.

Russell Thornton’s mission, on behalf of the government, was to clandestinely make his way into French Sudan, locate the ostriches, and secure a flock for South Africa, before the Americans or local French officials, who had tried and failed to develop their own ostrich farms in Algeria, caught on.

The post The Strange Tale of the Great Trans-Saharan Ostrich Heist of 1911 appeared first on FeedBox.