Author: Jacquelyn Thayer / Source: Atlas Obscura

In the summer of 2017, modern-day devotees of Solresol, an obscure 19th-century attempt to craft a universal language based in music, applied for an ISO 639-3 code. A successful application would add Solresol—under the three-letter code “sud”—to the standardized registry of all known languages organized by SIL International, a non-profit that studies and catalogues languages.

These supporters were seeking the formal recognition for Solresol that its creator was never granted in his own lifetime.But in January 2018, the bid was declined. Shortly before last year’s application submission, SIL established stricter criteria for registration. In their official response (which mistakenly lists the incorrect year of the rejection), the organization stated, “Solresol does not appear to be used in a variety of domains nor for communication within a community which includes all ages. Therefore the current request for a code [sud] for Solresol has been rejected.”

“I believe the rejection was mostly a result of poor timing and maybe a bit of high hopes,” says Dan Parson, a musician who in 2011 founded Sidosi.org, a hub for Solresol resources and discussion. There, as well as on social media and chat apps, the community connects over grammar analysis, translation projects, and historical research.

But what allure does Solresol hold in the 21st century for people like Parson? To better understand that, it helps to know about the constructed language’s history and rules.

In recent centuries, those who have sought to craft a universal language have done so by a variety of methods. The a posteriori approach usually draws together the vocabulary or grammar of a few common tongues, developing something like Esperanto in the process. An a priori language—one created from scratch—is often more scientific in its aims, seeking a taxonomic system to organize letters, words, and sentence structure.

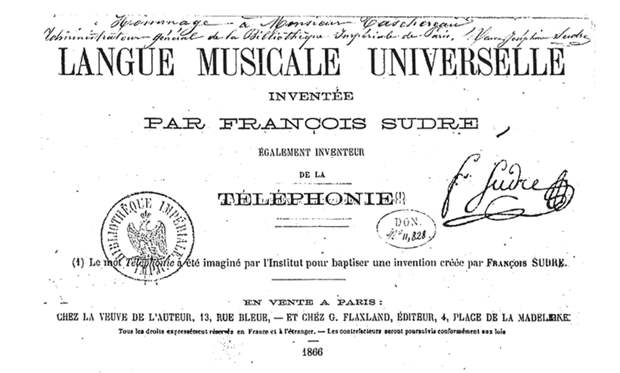

But for Jean-François Sudre, a music teacher in 19th-century France, the goal was to reredore solresol—construct a language—from music.

Sudre’s vision of a universal language transcended linguistic boundaries. From written and spoken word to melody, gesture, number, and even color, there are few ways that one can’t express Solresol, the language that Sudre spent more than three decades developing. But after his death in 1862, it was largely forgotten.

Fittingly, the global connections made possible by the digital age have forged a 21st-century life for Solresol. While books, such as Andrew Large’s 1985 The Artificial Language Movement, preserved general knowledge of the language’s history and structure, only over the past decade have websites, online communities, and education apps emerged to link hundreds of modern linguistic adventurers and music lovers through Sudre’s life’s work.

“When I became seriously interested in Solresol, I think it was really the result of the community that had just started building up again,” says Parson. As social technology has shifted, so has today’s Solresol community, migrating from a pioneering Facebook group to Reddit, Discord, and Sidosi’s own forums.

But while supporters have made efforts on these digital platforms to use the language in conversation, most discussion, though focused on Solresol’s grammar and vocabulary, occurs in English and other languages. Parson believes that moving Solresol beyond an intellectual exercise is key after the ISO bid rejection. “Though being told ‘no’ is always tough,” he says, “the obvious solution was just to start using Solresol more, as opposed to just talking about it.”

But the complex construction of Sudre’s system may explain the hurdles it can present for users.

Solresol began life as a sort of code. In his 2001 book Banvard’s Folly, the writer Paul Collins details the language’s earliest developments. Sudre set out in the early 1820s to link the 12 notes of the Western chromatic musical scale—A through G and the sharps and flats in between—with existing letters, as well as hand signals, in a system he called Téléphonie. Though he…

The post A Reprise for a 19th-Century Language Based on Music appeared first on FeedBox.